|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Ln May 2018, the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act 2018 was passed by Pakistan’s parliament and signed into law some weeks later, earning the country praise from rights advocates worldwide. The praise was well-deserved, as the law prohibits discrimination against trans people in almost all aspects, from education to employment, to access to basic services including healthcare.

Yet while no one really expected that things would get better overnight for the country’s trans people — long regarded as society’s outcasts — many of the law’s target beneficiaries say that, four years on, the law has barely made any impact on how they are treated.

“In our country, people don’t know about laws,” says transgender rights activist Zanaya Chaudhary. “According to law, if some companies are not giving you jobs on the basis of gender, you can take action against them. But we cannot take any action against any job rules (that discriminate against us) because if we do, we have to face consequences and we lose (our) jobs.”

Transgender activist Zanaya Chaudhary led a Women’s Day rally in March 2022. She and her peers demanded the full protection of the rights of the transgender community. (Photo from Zanaya Chaudhary)

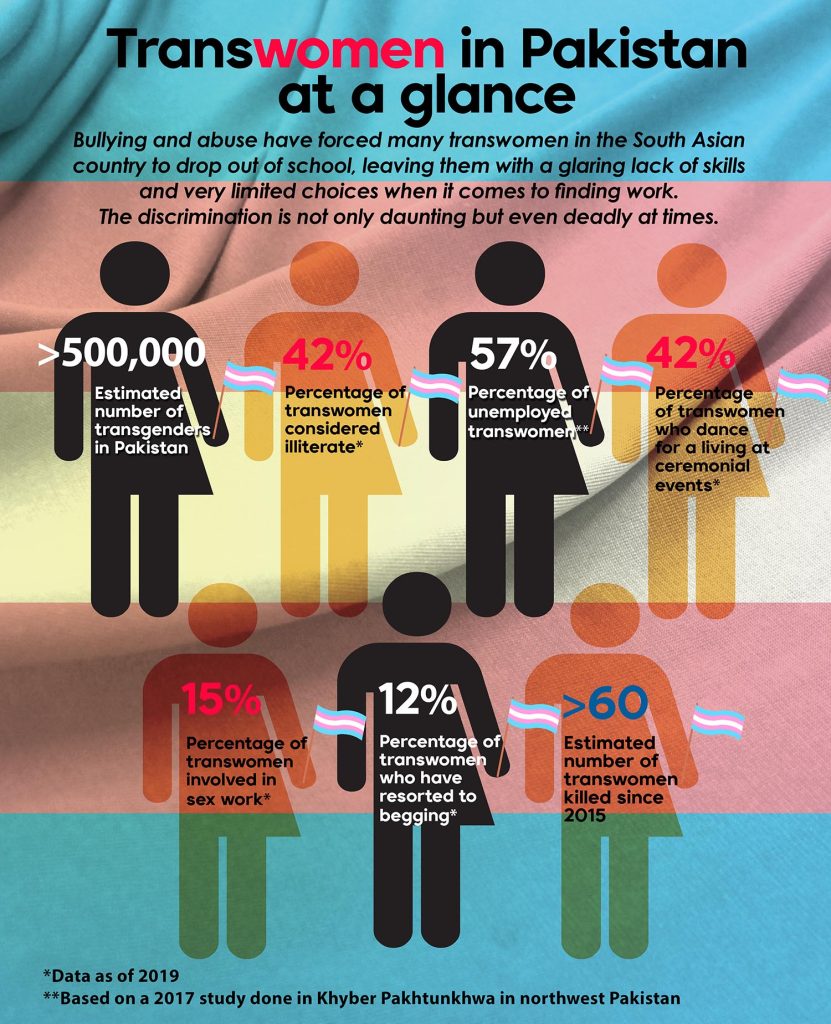

Estimates of the trans population in Pakistan, a country of 229 million people, run anywhere from 500,000 to two million. Shunned and discriminated against practically from the day their nonbinary gender is revealed, trans people in Pakistan usually find themselves struggling to find some means to support themselves. Transwomen in particular are often cast out by their own families at a young age. For the families, having such a member is a stigma. University of Peshawar academics wrote in a 2016 study: “Parents, when contacted, responded that relatives and people in the neighborhood give them unspoken or sometimes open remarks about their disability to produce a normal child.”

Many transwomen thus try to get by with barely any education — sometimes also because they are harassed or abused in school. A considerable number take up dancing to earn a living. In far too many cases, however, many are forced to turn to the sex trade or begging to survive.

One 2019 study cited 2016 data from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) that said 42 percent of Pakistani transwomen are “illiterate” and that only seven percent reached “higher secondary” education level. The same USAID data set also listed the top three sources of income for Pakistani transwomen as dancing (42 percent), sex work (15 percent), and begging (12 percent).

The University of Peshawar study, which was focused on Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in the country’s northwest, meanwhile said that of the transwomen surveyed, 57 percent were unemployed. Of those who had work, 37.5 percent said that they were in the sex trade, 31.25 percent in dancing, and 15 percent in begging. It also reported that 77 percent of its respondents were uneducated.

Strong social prejudice

When the researchers for the 2019 study conducted their own survey, 42 percent of their respondents also said that they were uneducated while 15 percent said that they had reached secondary level schooling. Forty-two percent said as well that their occupation was either dancing or begging, which, according to the researchers, showed “the strong social prejudice hampering the social acceptance for the transgender community.”

Comments activist Chaudhary: “The first and foremost requirement for any kind of private job is to have a bachelor degree. Unfortunately, many of us don’t have much education due to circumstances.”

A transwoman who wants to be known only by her first name, Saima, cannot agree more. She says that she has been unable to find work because she is uneducated. But at least her parents waited until she grew up before they threw her out of the family home. Saima then joined a group of transwomen, with whom she danced at weddings for a fee. But when the pandemic struck, restrictions were imposed, weddings were postponed, and their gigs dried up. Saima went from house to house to beg, but often the doors remained closed.

“They scolded me and made fun of me because of my identity,” she says. “They told me to go away and earn from other means.”

And yet, in pre-colonial times, Khawaja Sira or “third-gender people” were very much part of South Asian society and even revered as having “special powers.” The change came during the British era, when the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871 criminalized the transgender community. Although the law was repealed in 1949, attitudes learned and handed down from those times apparently persist in modern-day Pakistan, which has also evolved into a conservative country.

Sources: Open Democracy, ResearchGate

Indeed, the prejudice is so bad that even having a master’s degree may not be enough for a trans person to clinch a job in Pakistan. In one much publicized example, a trans identified in media reports only as Faizullah filed a petition in court in 2020, asking that her job application as university lecturer be accepted by the Punjab Higher Education Department (HED) and Punjab Public Service Commission (PPSC). The PPSC had rejected her application thrice; according to the Express Tribune, the third time it said that it was turning her down “on grounds of strict gender requirement of only male or female person.”

Eventually, Tribune said, Faizullah’s application was accepted, with HED “adding her name in the women’s category.” It is not known, however, if she was able to land the position.

Hiding identities

Some trans people at first try to pretend to be something other than what they are. Jannat Ali, an actress and an MBA who graduated with honors, says that she had to hide her “gender expression” while completing her education.

“It’s really important to educate yourself before you face society,” says Ali, who is also a trans rights activist. “The reason for hiding my identity was to easily complete my education without anybody questioning me.”

But she says that she continued to face problems while looking for a corporate job. Recalls Ali: “Whenever I went for an interview — even those referred by my close friends — the interviewer used to have questions about my (gender) expression instead of my academic talent, skills, and achievements. My mental health used to be affected badly, because I kept on thinking that there was no benefit in my getting educated.”

Marvia Malik, Pakistan’s first trans news anchor, has also said in published interviews that she had to work hard to break the taboos and to finally be accepted by a society that discriminates against her gender.

Activist Chaudhary, who has had a lot of experience pounding the pavement in search of work, remarks, “Whenever we search for jobs, we are told to hide our identity. And if we get a job, we have to avoid using makeup and dress like a male.”

“In the beginning,” she continues, “when I was in need of a job, I was told to behave and dress like a male. But when I did this, I still faced discrimination. The behavior of people didn’t change despite me hiding my identity.”

Pakistani transgenders used to be revered as belonging to a sacred third gender. That reverence disappeared during the British era with the passage of the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, which criminalized the community. (Photo by Zanaya Chaudhary)

Still, the likes of Ali, Malik, and Nisha Rao — who went from being a beggar to being Pakistan’s first transgender lawyer — show that at least there are trans persons who are making it through despite the odds.

Shortly after the act aimed at protecting the rights of trans people was passed four years ago, trans rights advocate and Be Ghar Foundation founder Ashee Butt had also said, “The passage of the bill into law … is a battle that is still only half won. We now face the challenge of fighting for the law to be enforced in its true spirit and that may take another a decade or two.”

To Jannat Ali, the fight begins at home. She has been quoted as saying that if the parents of trans people only nurtured and supported them, they could well end up in parliament or in the Prime Minister’s post. ●

Saba Chaudhary is an independent journalist and activist based in Pakistan. Her work focuses on human rights, gender, and social political issues.