|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The man Nagaenthran Dharmalingam was trying to borrow money from in 2009 for his father’s heart surgery had told Nagaenthran that he would first have to bring something to Singapore before he would get the cash. When he refused, the man assaulted him and threatened his girlfriend.

And so sometime in April 2009, Nagaenthran, then 21, crossed over the border from Malaysia to Singapore with “something” strapped on one of his thighs. He was stopped by Singaporean authorities, who found that the “something” he had was 42.72 grams of heroin. He was found guilty of drug trafficking and sentenced to death.

Over the course of his trial, doctors deemed him at risk, pointing to his IQ of 69, which by international standards defined Nagaenthran as mentally disabled. Despite numerous appeals, the Singapore state refused a stay of execution. Even the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights issued a plea on April 25, 2022, for the Singapore government to halt the execution of Nagaenthran and another Malaysian national, Datchinamurthy Kataiah. Two days later, however, Nagaenthran was hanged.

![]() Datchinamurthy’s execution was supposed to follow two days after, but it has been postponed — for now. He has a current civil case against the Singapore attorney general for the disclosure of his private letters, which would make his execution at this time “unlawful,” says one Malaysian newspaper.

Datchinamurthy’s execution was supposed to follow two days after, but it has been postponed — for now. He has a current civil case against the Singapore attorney general for the disclosure of his private letters, which would make his execution at this time “unlawful,” says one Malaysian newspaper.

Nearly a month earlier, however, Singapore had executed one of its citizens, Abdul Kahar bin Othman, by hanging as well. Abdul Kahar was 68 years old and believed to have developed an addiction to heroin after a stint in prison as a teenager. He was convicted of trafficking a total amount of 66.7 grams of heroin in 2013 and handed the death sentence in 2015. Under Singapore’s laws, anyone found guilty of trafficking more than 15 grams of heroin can be sentenced to death. Courts have the option to order the convict to serve a life in prison instead, but far too often they do not.

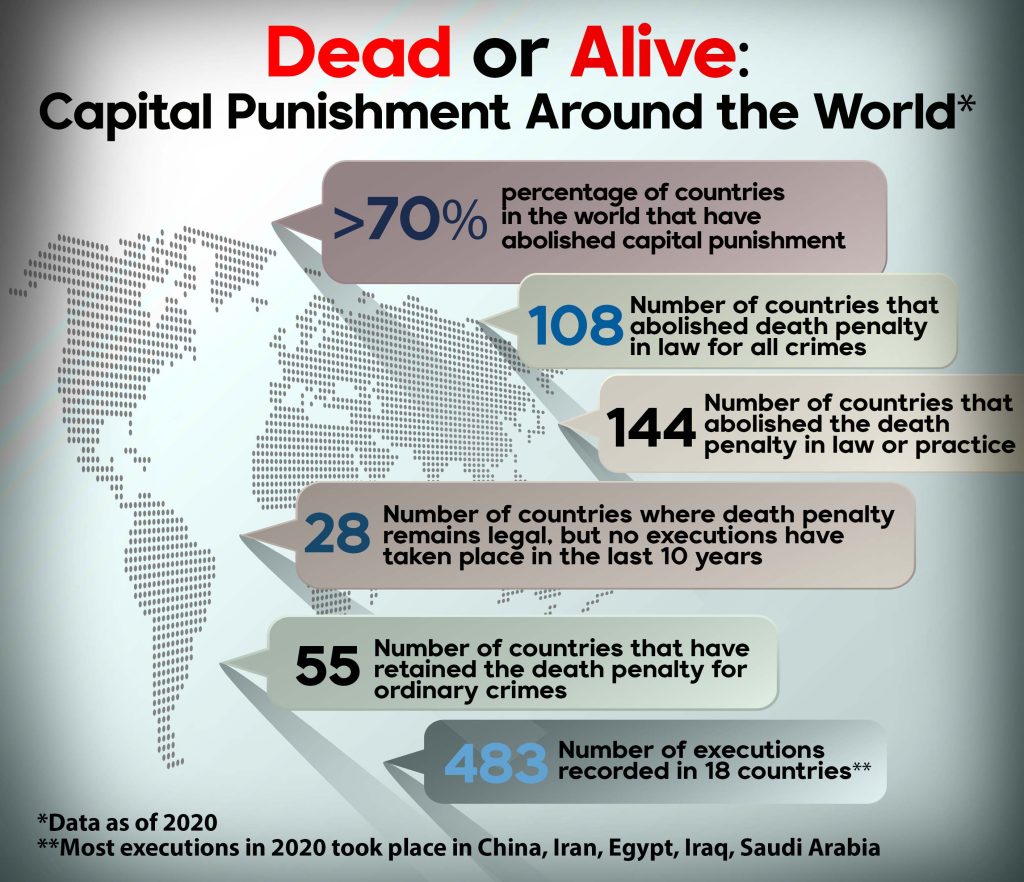

The death penalty is in effect in 54 countries in the world. In Southeast Asia, eight of the region’s 11 nations mete out capital punishment. Singapore’s death penalty has been in effect since it was a British colony and is used mostly for drug offenses, murder, and firearms crimes. In November 2020, Singapore was among the minority group of countries that voted against a UN resolution calling for a moratorium on the use of capital punishment. When the resolution passed, Singapore sponsored an amendment asserting the “sovereign right of all countries to develop their own legal systems, including determining appropriate legal penalties.”

No-nonsense ‘Disneyland’

Singapore has a reputation for being a clean, green Asian island paradise. But underneath this facade is an authoritarian state with unfettered power. This is why writer William Gibson called Singapore “Disneyland with the Death Penalty.”

The Singapore state insists that the death penalty is useful as a deterrent against crime, going so far as to say that over 80 percent of Singaporeans support it. The anti-death penalty group Transformative Justice Collective (TJC) notes, however, that people asserting that the death penalty works does not necessarily mean that the death penalty actually works.

The numbers cited by the government are also suspect; the authors of a 2018 study point out that the general Singaporean public actually knows little about the death penalty, and that exposure to information about the death penalty actually reduces support for it. The authors – all Singaporean academics – said the “support is … equivocal and nuanced.” Indeed, Abdul Kahan’s execution on March 30 prompted at least 400 Singaporeans to gather three days later in a park, in a rare show of public protest against the death penalty. Weeks later, demonstrators gathered again at Hong Lim Park in Singapore’s Downtown Core District for a three-hour vigil for Nagaenthran.

The state, however, also pushes the standard line that Singapore is safe because of the “tough approach” on drugs, i.e., the use of the death penalty on drug offenders. This creates the perception that Singapore’s safety and security is dependent on the existence of capital punishment. The state also creates a public paranoia that without it, Singapore would descend into lawlessness and become a city full of “druggies” who would accost people on the street.

While the evidence the Singapore state refers to is questionable, there is credible evidence that the death penalty does not in fact deter crime. When it comes to drugs and the death penalty especially, Oxford University professors Roger Hood and Carolyn Hoyle write that “in all 33 countries with the death penalty for drug offenses, it has been argued that the death penalty is an indisputable deterrent to drug trafficking, but no evidence of a statistical kind has been forthcoming to support this contention.”

In truth, there seems little correlation between capital punishment and drug cases. Countries with the death penalty like the United States and Iran have high rates of drug abuse, while those without a death penalty, like the Scandinavian states, have low rates of drug abuse. Interestingly, Iran recently abolished the death penalty for certain drug crimes, while the United States, which imposes the death penalty for large-scale drug trafficking, has yet to execute anyone for a drug offense.

More ethnic minorities on death row

Moreover, in Singapore, the death penalty seems to have ended up targeting the marginalized. It is often the drug mules, not the drug lords, who are executed. Conditions on death row are abysmal and would be considered a violation of international human rights. Death row prisoners are kept in isolation in small, sparse cells with just a toilet and a mat. They have access to a bucket for washing and are not allowed out for air or exercise.

This is different from the cases of crime lords living large in Singapore, as can be seen in the case of Ang Boon Seng, a sex trafficker and a pimp who ran one of the country’s largest sex work rings. He lived in a mansion, while other people were forced to make millions for him.

In a surveillance-heavy state like Singapore, where every aspect of residents’ lives is subject to scrutiny by the state, it is hard to believe that the Singapore government did not know of his criminal activities. Yet Ang operated with impunity for four years.

And when he was finally brought to justice, he was sentenced to just 35 months in prison — a mere three years. Ang’s wife, his accomplice, who was exploiting Filipino women for his operation, got away with a paltry 10 weeks behind bars.

Conversely, Nagaenthran was hanged for less than three tablespoons of heroin.

The stark contrast between how a millionaire ethnic Chinese crime lord was treated by the Singaporean justice system versus how a poverty-driven, mentally disabled Indian Malaysian was treated by that same justice system raises questions about who the system serves and protects. In its petition to save Nagaenthran, TJC pointed to a class bias in the Singaporean justice system.

There is a race bias as well. Aside from Abdul Kahar, Nagaenthran, and Datchinamurthy, at least six other men have been issued execution notices. According to TJC, all six had their execution postponed because of “legal applications filed to the court.” Although they are a mix of nationalities, all six are either ethnic Indian or ethnic Malay. Members of these two ethnic communities are significantly overrepresented on Singapore’s death row. They make up only 22 percent of the city state’s population but 85 percent of its death row inmates. This significant overrepresentation mirrors the situation in the United States, where a racist justice system also disproportionately sentences Black people to death row.

Beneath Singapore’s clean and green facade is an authoritarian state that some have dubbed “Disneyland with the Death Penalty.”

In a speech before the Asia Pacific Forum on Drugs in 2017, Singapore’s Minister for Home Affairs and Law K Shanmugam said that “death penalty abolitionists … write romantic stories” about those found guilty of drug trafficking. “Romantic,” however, is ill-suited for stories like that of Nagaenthran. A mentally challenged man was forced to become a drug mule and wound up spending nearly 12 years on death row which, by many accounts, led him to deteriorate further psychologically.

Nagaenthran last saw his family in the courtroom the day before he was hanged. Reportedly, his last words to them were his repeated cries of “Ma!”

The pain, fear, and loneliness he must have felt in his last seconds will forever haunt me and all the other activists trying to overturn this practice. States should not have the power to murder people, no matter their crimes. It is time to end capital punishment, once and for all. ●

Sangeetha Thanapal is a Singaporean social critic and activist who is currently based in Australia.