|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The weather was nice, not too hot and not rainy either. I did not receive any direct invitation to the hearing but I went anyway. It was announced in public, so I assumed everyone was welcome.

The hearing was at an auditorium at the Governor’s Palace in Banda Aceh, the provincial capital. When I got there, there were already many people milling about, including key figures in the field of conflict and resolution in Aceh. I recognized one person as being from the Free Aceh Movement (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka or GAM). He was sitting and chatting with some foreigners. I also saw someone in military uniform. Maybe he was sent to attend the hearing since it was an official government event. But both he and the GAM person only stayed for the opening and left before the testimonies started.

The rest of the guests were mostly prominent rights activists in Aceh. They looked happy. In fact, with all those smiling faces and Acehnese music playing in the background, I felt like I had crashed a kenduri or feast. For the rights advocates, it was probably a very important event after the long journey of fighting for justice after the bloody conflict in Aceh.

Located on the northern tip of Sumatra island, present-day Aceh is thriving and developing as a halal tourist destination. It is still one of the poorest provinces in Indonesia, but shopping malls are popping up and expanding. Aceh has also been attracting visitors, both local and international. And while political controversies break out now and then, Aceh has been generally peaceful for almost two decades now.

Present-day Aceh is a thriving halal tourist destination with landmarks like the Baiturrahman Grand Mosque drawing in visitors. But underneath the province’s peaceful atmosphere remain the scars of decades of conflict.

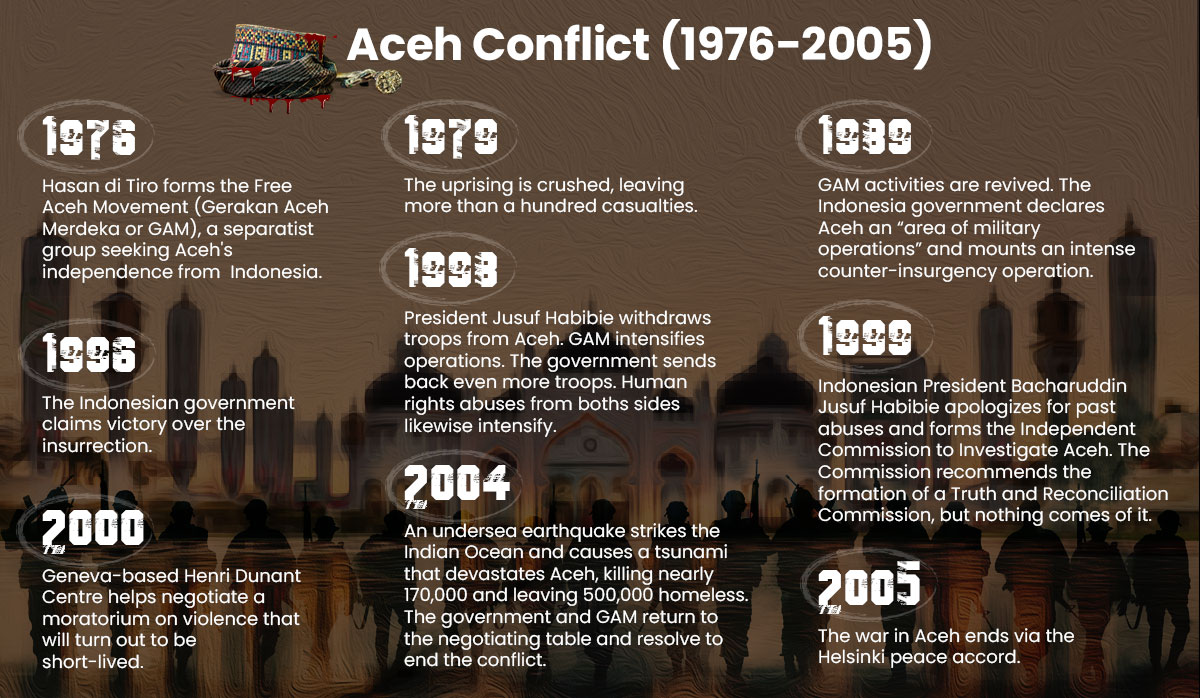

From 1976 to 2004, however, Aceh was a battlefield for GAM and the Indonesian military. In 1976, erstwhile Indonesian diplomat and GAM founder Hasan di Tiro launched an armed bid to make Aceh independent from Indonesia. It was a conflict that would last nearly three decades and claim thousands of lives. According to Amnesty International, between 10,000 and 30,000 people, including many civilians, were killed during the conflict.

“There is overwhelming evidence that many of the violations directed against civilians by Indonesian security forces and their auxiliaries may amount to crimes against humanity and that human rights violations and abuses committed by both sides of the conflict amount to war crimes,” Amnesty International wrote in its 2013 report on Aceh, nine years after the fighting had finally stopped. “Despite this, only a handful of the crimes have been investigated and no one has been prosecuted before independent civilian courts.”

This was why that hearing held on a day in November 2018 was so significant, as were the other two public hearings for survivors of the conflict that followed months afterward. I went to all three. I could not believe that these testimony hearings of conflict in Indonesia — where, according to many studies, democracy is on the decline and justice is still precarious — were taking place.

And so I listened to all the stories of the survivors and victims’ families. I wanted to be hopeful that this would mean they would finally get justice or closure. Or both. But each time I came away feeling the hearings were all ceremonial, and that they would easily disappear from memory.

Speaking the truth

There was supposed to be a fourth hearing, but it got canceled because of the pandemic. The Aceh Truth and Reconciliation Commission (known more popularly by its Bahasa Indonesia acronym KKR) was also supposed to release this year a final report on the hearings and the statements it took from more than 5,000 conflict survivors between December 2017 and March 2020.

But that doesn’t look likely to happen now. Neither does the passage of a new national Truth and Reconciliation Commission Law, which the KKR needs to access funding from the national government not only to properly investigate the abuses committed during the conflict but also for the victims’ reparations.

Then again, it took 11 years after the peace pact between GAM and the Indonesian government was signed for KKR to be established in 2016. And even then, it was formed only after immense pressure from rights advocates and victims’ groups.

KKR’s first batch of commissioners recently finished their mandated five-year term. The new head is the only holdout from the previous KKR. I am told he was the weakest among the previous batch of commissioners, having produced nothing outstanding during his first term. The new commissioners, meanwhile, come from a variety of backgrounds, none of which involves rights advocacy.

Among KKR’s main duties are to reveal the truth and protect witnesses and victims, as well as the people involved in the truth-telling process. The Testimony Hearing Meeting or Rapat Dengar Kesaksian (RDK) is part of the truth-telling mechanism. The first had testimonies from 14 victims of torture. The second took two days in July 2019, during which 15 victims and families of the disappeared spoke. The third was held in November 2019 and focused on cases in North Aceh, Bireun, and Lhokseumawe Region. Twenty victims testified.

During the RDKs, those who spoke went onstage one by one, accompanied by a KKR representative. By then, the joyous atmosphere would be gone and replaced with solemnity. The commissioners would ask those onstage questions and they would reply. Some stopped in the middle of narrating their story and could barely go on. The survivors and their families were mostly civilians; there were victims of both the Indonesian military and GAM. Some told of witnessing a family member killed right in front of their eyes, some found their loved ones already dead, and some had no idea whether or not the father or brother who was carted away was still alive. “There is no grave to visit,” they said.

A wife with a newborn in her arms watched her husband killed; another had her spouse kidnapped in the middle of the night. A survivor was tortured and raped by soldiers. A mother who lost contact with her son still hopes he will return home. Some also said their family was lucky to receive their relative’s corpse, even if it was riddled with wounds because other families are still looking for bodies or graves. An old man started sobbing while recalling how he was beaten so badly by GAM he was left disabled for life. One story of violence after another came out of their mouths, in voices so low and soft they could barely be heard, even with the use of microphones.

They all looked disheveled and — I still find it hard trying to find the right word — looked so humble, if not poor. As if they had not gone through enough tragedies, most of them also talked about having economic difficulties. Was it the conflict that made them destitute? Or were those affected the most people who had little, to begin with?

The conflict between the Indonesian military and the Free Aceh Movement lasted nearly 30 years. An estimated 10,000 to 30,000 people, many of whom were civilians, were killed.

No forgetting

Surprisingly, most of them said that they had forgiven the perpetrator, whosoever it was. The one thing they all requested was for the war to never happen again. This simple request left me heavy-hearted. I guess every single person in that room realized that justice would most likely never happen in this country. A question crossed my mind: So what’s next? What will happen to those who endured war and still have scars on their souls while the rest of us enjoyed peace?

I am Acehnese but I was spared the horrors of the conflict. My family had moved away before the fighting began. I came back to Aceh only in 2005; I am an engineer by training and I quit my job at an architecture firm in Jakarta so I could help in the rehabilitation efforts in Aceh following the 2004 tsunami. That disaster had flattened Banda Aceh and killed nearly 170,000 people in the province alone. But it helped stop the fighting and eventually led to the 2005 Helsinki peace agreement between the Indonesian government and GAM.

I did not know what to expect from the RDKs. But I did know they were not supposed to be trials. War crime tribunals are not in the ambit of KKR, which was formed to resolve past gross human rights violations out of court. It has the right to decide whether to grant compensation, restitution, rehabilitation, or amnesty.

The RDKs’ objectives are to educate the public and have people know which factors caused the alleged past human rights violations, as well as to obtain public recognition for witnesses/victims and facilitate social recovery and rehabilitation for them. These sound like simple objectives, but they are absolutely important and at the same time difficult.

Why important? Because the public needs to know the truth and at the same time, the RDKs help restore the victims’ dignity by letting them exercise their right to speak. Why difficult? Because the RDKs’ success depends on the number and diversity of people who acknowledge them, attend them, and hear the stories.

The bigger the number, the bigger the impact. The more diverse the audience, the stronger the recognition. So the victims are identified and can be helped. So the same crimes are not repeated. So the echoes of the voices telling the stories reverberate longer, even if they cannot be louder.

Sources: The State of Conflict and Violence in Asia, Indonesia: The Aceh Peace Agreement, Human Rights Watch

Unfortunately, there was not much response from the public during the three RDKs. A historic event was taking place but there was no headline about it or special reports in the local and national media. I had been disappointed to see empty seats at the RDKs. I would begin by standing in the back room, but I would end up sitting as close as I possibly could to the stage. I wanted to hear everything. But I guess there were just not many more who were as interested as I was.

According to Azhari, a rights advocate active in Aceh, there are two main reasons for this tepid response to the RDKs. One is that for Acehnese, these kinds of stories are common. They aren’t new, he says, except with RDK, the stories are given a stage by the government. Symbolically and principally, this is highly significant. And yet the handful of high-ranking government officials who attended the RDKs did not really stay long. Second, Azhari says, the RDKs have lost their momentum; they took place long after the peace agreement was signed. He notes as well that the local and national media usually do not give much space to human rights violations.

Nevertheless, the previous KKR head had declared the RDKs a success. He told the media that all three RDKs were filled with people of various backgrounds.

What I saw, however, was that the majority came from the same circle of human rights activists and organizations, and they were repeat audiences. If the RDKs’ main objective was to educate the public, why were they preaching mostly to the converted? Had more students, civil servants, laborers, and white-collar workers listened to the stories, perhaps the testimonies would have had an impact.

In the absence of a national Truth and Reconciliation Commission Law, the final report on the victims’ statements and RDKs has taken on more significance, if only to help the survivors gain protection and reparations. But I have heard its progress has stalled, partly because of the change in the membership of the KKR. I have no record of the testimonies myself; we were prohibited from recording and taking notes and photos during the hearings.

But should the report ever come out, would many people be interested to read it? Would there be people who would realize that the stories it contains hold lessons for all of us? ●

Aulina Adamy is an associate professor in disaster management at the University of Muhammadiyah Aceh. She is also active in pro-democracy and election observation activities.