When she first started street vending in the late 1990s, Nguyễn Thị Gấm would have a long pole across her shoulders, with a pot of porridge dangling from each end, and vie for the attention of potential buyers in the form of a verse: “Pork ribs, mussel, green bean, who will buy my porridge?”

Now in her early 50s, Gấm can no longer carry her two pots of porridge in the same manner. Instead, she has them loaded on the back of her bicycle and she now has a loudspeaker to reach more buyers in Hanoi, with less pressure on her throat.

Gấm says that she has made a good living from selling bowls of porridge every day from seven a.m. until 12:30 p.m., and then from two p.m. until her food is sold out. “Except for rainy and stormy days, I can earn decently just by selling porridge,” she says. “I have raised two children and sent them to college (from this).”

Street vendors are a common sight in major Vietnamese cities. Here in Hanoi, images of street vendors and their colorful products have long contributed to the uniqueness of the country’s capital. The vendors’ stories, however, are often filled with hardship and discrimination. And since the pandemic hit in 2020, life for them has gotten even harder.

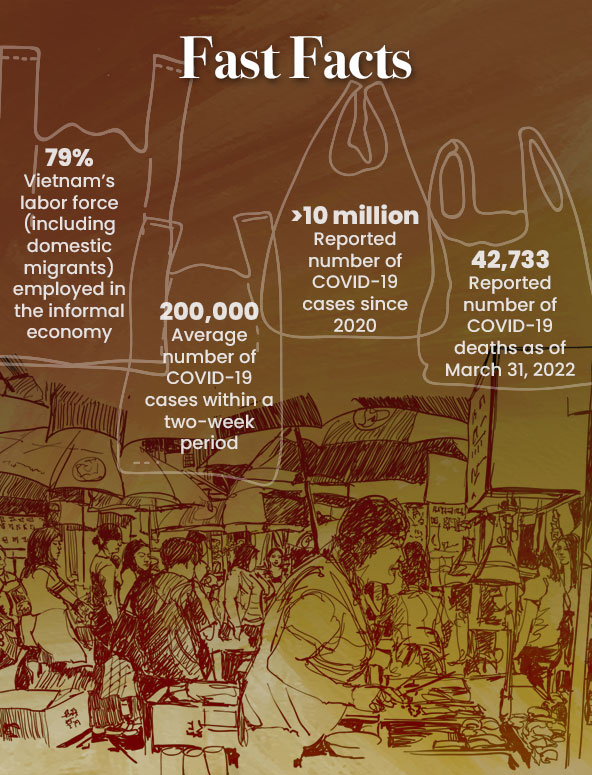

Vietnam was one of the supposed success stories during the first wave of the pandemic in 2020. But the virus has since spread rapidly in the country, which has now been recording 200,000 cases a day on average for the past two weeks. Since 2020, it now has had more than 10 million confirmed cases of COVID-19. As of March 31, 2022, the country also has had 42,733 reported deaths from the virus.

Many street vendors in Hanoi are migrants from the provinces, with no registered addresses in the city. This has made them ineligible for government aid during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Photos by Vũ Hồng Trang)

Even though travel restrictions have now been lifted throughout Vietnam to help the economy recover, rules and regulations still vary from city to city and region to region. Since late 2021, Vietnam has consistently reported new records in the total number of daily cases, with Hanoi currently topping the chart.

According to the health ministry, the government has administered more than 200 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines, covering about 89 percent of the country’s 99 million people. Gấm says, though, that she and other street sellers were the last ones in the neighborhood to be jabbed at the local vaccination center as “they are not citizens of Hanoi.”

When queried on the implementation of the vaccination policies, the head and vice-head of the neighborhood would only say, “We only followed rules.” Then again, since the beginning of the pandemic, Gấm and her colleagues have experienced being looked at unkindly by some of their neighbors, most likely, Gấm says, because they “wandered around a lot” and were considered as “likely to spread the virus.” Gấm says, “Some parents even told their children to pass by our apartment quickly to avoid being infected.”

In search of a livelihood

There are no official statistics on street vendors in Hanoi. But many of them are migrants from the provinces like Gấm, who goes back to her village only on holidays and on rare occasions that her family needs her for some matters.

“It is sad to live alone in Hanoi, but we cannot find any job here in the village,” says Gấm, whose street vending has been able to support her farmer husband, two children, and her grandparents.

In her village in Nam Định province, which is some 85 kms away from the capital, all her peers have also headed to different cities to earn a living to help support their families.

According to Article 3 of Resolution 39/2007/NĐ-CP, street vendors are categorized as unregistered, unregulated, and untaxed traders or freelance laborers (lao động tự do). In reality, street vendors do not have a legal space or a license to sell their products, yet they are not entirely forbidden from providing services.

In 1986, the communist government embarked on a set of socio-economic reforms to lift the country out of impoverishment and international isolation. Known in Vietnamese as Đổi Mới (restoration), these reforms shifted the centrally planned economy to a market–based and multisectoral one. In addition, land privatization programs in the 1990s converted about one million hectares of farmland to non-agricultural use, which put pressure on farmers and resulted as well in the expansion of the informal sector that employs the non-agricultural workforce.

As in many other developing countries, street vendors face increasingly restrictive policies due to the top-down modernization process. Instead of tackling the root causes of the informal economy — particularly public-sector corruption, poor legal system, and unfavorable business conditions — the Vietnamese government came up with makeshift measures that have taken a toll on the livelihood of street vendors.

Street vendors are often seen as unhygienic, unsafe, outdated, and thus out of step with Vietnam’s modernizing society. As late as June 2020, in fact, the host of a popular TV program even went as far as likening street peddlers to “parasites” on the streets of major cities in a TV program. That stirred a heated public debate in Vietnam on the structural discrimination against these marginalized people in society. The TV host later apologized for his comments.

In Hanoi, street vendors have been banned from designated areas since 2008 to promote the so-called image of the capital city as a modern economic hub. In a restrictive country that offers little room for citizens to protest against discriminatory state policies, this highly mobile, marginalized workforce has had to find its own ways to negotiate and navigate the system in defense of its members’ livelihoods.

“We always have to look out for local policemen,” Gấm says. “If caught, our wares will be confiscated and we will have to pay a fine.”

Lương Thị Sinh, a cookie seller from Thái Bình, says that the fines could amount to her one-day income in Hanoi.

Vaccinations in Vietnam are well underway with 89 percent of the country’s population vaccinated so far. Street vendors, however, do not figure high on the priority list. They were among the last to receive jabs in vaccination centers.

“There is no receipt,” says another vendor who has paid fines of US$10 and US$20 in the past. “We just have to pay whatever amount was asked.”

But Gấm and Sinh have both learned how to deal with the local police. The vendors make sure they are near the ward boundaries when they sell their food on the streets. Explains Sinh, “If the police are coming, I will just cross the street and be in a different ward. They cannot fine anyone beyond their area of management.”

Left in the dark

It would help, of course, if they were always informed of new policies. The vendors would then be able to comply. But the sudden top-down travel restriction policies during the pandemic caught them off guard. Usually, citizens would receive such information online or through the community leaders. Yet for marginalized populations, access to official information leaves a lot to be desired.

Hanoi has imposed social distancing policies twice, in late March of 2020 (from March 23 to April 7) and in late July 2021 (starting on July 24), both at very short notice. The former period was essentially a preventive measure, as there were only a dozen cases. The latter was more of a reactive step, given a spike in community transmissions in Ho Chi Minh City since the National Reunification Day on April 30, 2021. For the latter, the announcement was made at 11 at night on July 23 and came into force at six a.m. the next day.

Sources: World Health Organization, OXFAM in Vietnam

At the time, Gấm did not have access to the internet; she did not have a smartphone. For years, she had used an old Nokia mobile phone, which allowed her to receive and return calls, mostly from families and customers. Yet with her phone unable to receive the blast announcement, she should have at least received notification from the local leaders. But she didn’t.

“He [head of the neighborhood] never saw us (street vendors) as residents of the neighborhood,” says Gấm. “For him, we are nothing but outsiders.”

And so, on July 24, 2021, Gấm was still selling porridge on the streets — and unaware that she was technically breaking the latest rule in the city. It was one of her regular clients who told her that the lockdown had just begun. Another kind-hearted client asked her child to drive Gấm to her rented apartment so that she would not be seen and caught by the police.

During the lockdowns, Gấm had to stay put in Hanoi. With no source of income, she relied on her savings. According to the Government’s Resolution 68 NQ-CP, street vendors, though not falling into any group of registered businesses, were still eligible for a lump-sum aid of VND 3 million (around US$130). Yet Gấm says that she was not eligible to apply for this aid in Hanoi, because she did not have household registration in the capital city.

Cookie vendor Sinh was also denied the financial assistance, even if she was able to go back to her hometown. Apparently, she had never registered as a freelancer with the local authorities in Thái Bình.

Nguyễn Thị Hà, a 60-year-old Hanoi resident who has been hawking xôi (sticky rice as breakfast) for the last 20 years, was luckier. She received the aid in two installments — five months after her application, which had her going through numerous bureaucratic hurdles.

“It is very humiliating to ask for this assistance,” says Hà. “I only do so because I do not have any savings.”

These days, travel restrictions have been lifted. But with a surge of COVID-19 cases ongoing, people are reluctant to go out, which means less income for the street vendors. The mushrooming of food delivery services based on smartphone applications in recent years and their increase in popularity during the pandemic has further put the street sellers at a disadvantage.

Gấm at least now has a smartphone. She is still learning how to use it, though, and she is not finding it easy. “I try in the evening, but only after I prepare food for the next day,” Gấm says. “I feel too exhausted just to open my eyes.”

She feels she is “too old to learn anything now.” Gấm says, “I cannot catch up with the young people, let alone compete with them.” ●

Vũ Hồng Trang is a social entrepreneur from Vietnam and a gender advisor at Equal Asia Foundation.