On January 11, 2022, the Thai Cabinet approved the draft Act on Media Ethics and Professional Standards, which will then be up for parliamentary debate and approval. In principle, it claims to support self-regulation by media professionals. But many still have concerns over it becoming another tool for state censorship.

According to the government website recording cabinet resolutions, the draft proposed by the Department of Public Relations has nine important points, including the setting up of a media council that will promote and protect media rights and freedoms while overseeing adherence to media ethics.

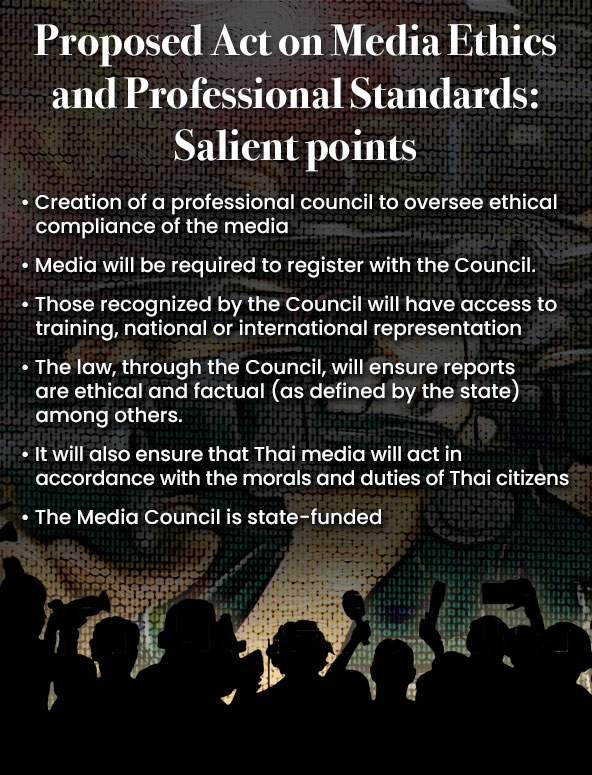

In summary, the law aims to create a state-funded Media Council that will oversee the ethical compliance of media professionals or organizations applying for membership under the Council. The media recognized by the Council will have access to privileges that the Council may provide, such as training or national or international representations.

Although the ethical standards have yet to be established, the Council can sanctions violations through warnings, probations, and public reprimand.

A crowd control unit of the Thai police stand in the way of reporters.

Necessary evil?

At present, Thailand has no law that directly addresses the work of the media as a whole. Apart from Section 35 the 2020 Constitution, which provides that the media shall enjoy the rights and freedoms ‘in presenting news or expressing opinions in accordance with professional ethics’ there are only regulations on specific prohibitions in various laws. The 1997 and 2007 constitutions had similar provisions for media freedom.

It has been agreed loosely among the Thai media that they would apply self-regulation. This means that the media would monitor and scrutinize unethical coverage or complaints without any intervention from the state.

Chavarong Limpattamapanee, senior editor at Thairath Daily and currently president of the National Press Council of Thailand, which was established in 1997 to promote self-regulation and press freedom, said in a public panel on January 20, 2022 that the draft law was a necessary alternative to the military government’s attempts to control the media after the 2014.

He said there have been several attempts to draft a law that directly addresses media operations such as the draft Protecting and Promoting Media Ethical Standards Act in 2010 after the deadly crackdown on red-shirt protesters. There were also attempts before 1997 to have a media council enshrined in the constitution, he said. The attempts all failed, giving the media the freedom to regulate itself.

After the 2014 coup, the junta government led by Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha established a National Reform Council (NRC) to draft laws seeking to address specific issues deemed important by the junta. The NRC found, for instance, that self-regulation was flawed, and a regulatory law was necessary on top of self-regulation.

The NRC thus proposed to establish a media council that could intervene in professional organizations’ decisions and impose financial penalties on media outlets that published news deemed ‘unethical’. The proposal was heavily opposed by the NPCT as an infringement on self-regulation.

The National Reform Steering Assembly (NRSA) that replaced the NRC in 2016 added to the NRC’s proposal a provision to require media workers, under a broad definition that included even online influencers, to apply for a professional license from the state. This draft was strongly opposed by both the media and the general public, prompting its withdrawal by the NRSA. However, the authorities would still be represented by an ad-hoc committee member in the first five years of the media council’s operations.

The law did not make any significant progress until the formation of the National Reform Committee on Media Communication and Information Technology, another entity responsible for the reform-related laws after the 2017 Constitution. At this stage, representatives from professional media organizations were summoned by the Department of Public Relations to take part in drafting the law.

The media representatives offered an alternative draft to the existing controversial version, resulting in the final version approved by the Cabinet in January 2022, which does not impose state registration and allows only social sanctions like cautions and reprimands.

Pradit Ruangdit, former president of the Thai Journalists Association (TJA), said that the media formed a minority opposition within the Media Reform Committee and that they opposed radical proposals like compulsory registration and financial penalties before they decided to quit the NRC and joined the opposition movement against media registration.

Chavarong said it was better not to have this kind of law but at this time, it was either this law or state intervention.

Fears of more censorship

The issues that most worries media people seem to be the legal definition of media, media ethics standards, state membership in committees, and an annual 25-million-baht (around $747,384) budget.

On January 17, 2022 the Thai Media for Democracy Alliance (DemAll), a broad network of mass media and content-related workers, published a statement demanding a delay to the first parliamentary reading to allow professional media associations to conduct another public hearing, citing concerns about the issues mentioned above and other technical matters like the selection committee for the Media Council.

A reporter from Voice TV, now an online and satellite media outfit, covering the frontlines as the police cracked down on protesters in March 2021.

Rittikorn Mahakhachabhorn, general manager at Voice TV, formerly a TV station that now operates online and via satellite broadcasts, said that despite improvements to the draft, the state’s intention to take control of the media is still not out of the equation because the Council is funded by the state.

He said ‘morals’ and ‘duties of Thai citizens’ are terms that allow a wide range of interpretations, on which news outlets may not reach a consensus.

Rittikorn thinks that the law will inhibit the media more than protect it if the media ethics can be broadly interpreted in this manner, citing his workplace experience of being punished over 20 times by the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission

Nattapong Malee, a citizen journalist from Ratsadon News, also raised concerns about media ethics, saying that it may cause him more difficulty working in the field.

When curfew restrictions were enforced under a state of emergency in Thailand during COVID-19, police asked the media covering the protest to produce their press cards and certificates from their workplaces and the authorities allowing them to work outside during the curfew, things that citizen journalists find difficult to acquire. Nattapong was arrested while broadcasting the Din Daeng protests in September last year for failing to provide these documents.

Even when the curfew was withdrawn, the police asked the media to produce their press cards to enter areas they had secured even if these were open public spaces.

Sources: Human Rights Watch, The Bangkok Post

Nattapong said that if the law is passed, the authorities may come up with more reasons to ban citizen journalists who may not be able to register with the Council because they have no media documentation.

Somkid Puttasri, editor-in-chief of The 101.World, an online media company, shares Rittikorn’s view of the broad interpretation of media ethics. Although it figures in media regulations in many countries, in the Thai context, where interpretations usually benefit the authorities, limits to press freedom must be written as clearly as possible.

Toward more effective self-regulation?

Somkid said the question is how the regulation process can improve the media industry, ensure its independence from state influence despite being funded by it, standards so that the work of the media has a positive impact on society.

He added that the draft law offers no concrete details in terms of a regulatory system that can guarantee the Council’s independence, regulatory efficiency, and genuine media representation for the public benefit.

Mongkol Bangprapa, president of the Thai Journalists Association, said the current self-regulation system only applies to members of the National Press Council and professional associations, which means an outlet can easily avoid scrutiny by not joining or resigning their membership. As a result, there is a huge hole in media self-regulation where this law offers a solution.

The TJA president said it is not surprising that the media and the public would oppose this kind of law coming from a government that has a history of censorship. Yet the law will result in more effective self-regulation and the public should be vigilant about any negative changes to its content in the parliamentary readings.

“We understand that the laws passed by every government, especially governments that we perceive as originating from a coup, will try to interfere with the media. Being cautious like this is a good thing. Making society and all the media help each other to be vigilant that the legislative process does not get hijacked is a good thing. But suspicion alone and rejection based on suspicion may sometimes stop something that is making progress,” Mongkol said.

“When the fundamental principle is not distorted, let’s first open this door, then it’s up to everyone to help.” ●

This article is a condensed version of the original, first published by Prachatai on February 1, 2022. It is republished here by the Asia Democracy Chronicles with permission. Follow this link to read the full article.