Her schoolbooks are piled on her table at the family home, but there is little chance she will be using them again. In fact, the 10th grader is no longer living there and has left her village as well.

“I thought I would go to school when COVID-19 was over,” says the 16-year-old who wants to be known only as Poppy. “I’d play with my friend. The school reopened after 15 months, but I will not go to class anymore. Now I am spending my life with my husband’s family. I left my village and school. Now I live in Dhaka City.’’

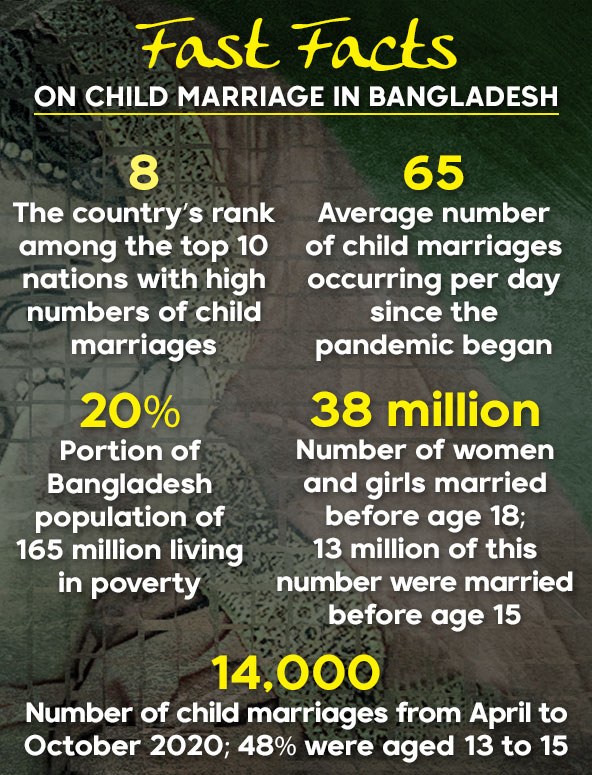

Poppy is only one of the thousands of schoolgirls across Bangladesh who became brides during the pandemic. A study conducted by the Manusher Jonno Foundation (MJF) in late 2020 says that nearly 14,000 child marriages took place in 21 districts of the country between April and October that year. Of that number, about 48 percent involved girls between the ages of 13 and 15. MJF coordinator Arpita Das says that since the pandemic began, there have been on average 65 child marriages per day in Bangladesh.

U K M Farhana Sultana, a project manager at the Action for Social Development (ASD), says that her organization has been doing “a lot to prevent child marriages since 1988.” But she says, “Our research shows that the rate of child marriage has increased the most in the COVID-19 situation. It seems that child marriage has become a bigger curse for girls than a virus epidemic.”

Many young girls in Bangladesh have been forced into marriage by their poverty-stricken families. The situation has gotten worse during the pandemic. (Photo used for illustrative purposes only.)

Bangladesh has had a law aimed at preventing child marriages for nearly a century (including the colonial era). Rights advocates say that the fact that the problem persists shows that the practice is deeply ingrained in the country’s culture and that the government has been unable to enforce the law. Worse, one of the major drivers of the increase in child marriages during the pandemic is the latest version of the law, the Child Marriage Restraint Act, 2017, or CMRA.

CMRA 2017, which replaced its 1929 version, has one particular provision that is still being debated now. Indeed, while the law stipulates that girls must be at least 18 years old and boys 21 to be legally married, a provision that appears in Article 19 implicitly allows marriage even for those below the legal age “under special circumstances as may be prescribed in the rules in the best interests of the minor, at the directions of the court and with the consent of the parents or guardians of the minor….”

The government had inserted the provision supposedly in response to possible “accidental or unlawful pregnancies” of unwed girls. But rights advocates argue that marriage is no solution for such; they add that because “special circumstances” have been left undefined, it is open to interpretation and can mean anything.

Bangladesh Women’s Council President Fauzia Moslem says, “The special provision of the new law has increased child marriage in the COVID situation…. Parents give their minor daughter in marriage, citing as reasons poverty and insecurity caused by the pandemic.”

One step forward, three leaps back

Bangladesh has long been notorious for child marriages. More than 20 percent of its 165 million people live below the poverty line, and for many families, marrying off daughters as early as possible means fewer mouths to feed. Concerns about daughters getting involved in premarital sex also push some families to look for marriage partners for their girls as soon as they hit puberty.

According to an October 2020 United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) report, the country has the highest rate of child marriages in South Asia and is eighth among the world’s top 10 nations with the highest numbers of these marriages. It also says that 38 million of Bangladesh’s current total population of women and girls were married before the age of 18 and that 13 million of those girls were married before the age of 15.

UNICEF says that early marriage not only robs a girl of her childhood, it is also detrimental to her physical and mental health. Moreover, a child bride is likely to stop schooling, and would thus have fewer opportunities for employment later on. In some cases, child brides end up being trafficked into the sex trade.

In 2014, Bangladesh pledged to stop child marriages before the age of 15 by 2021. No one talks about that pledge now, but there had been another aim to eradicate child marriage altogether by 2041. Before the pandemic, child rights advocates say, child marriages were still happening, but they were on a slow, downward trend in Bangladesh. In part, this was because of the monitoring of many rights organizations, as well as of schoolteachers. In March 2020, however, schools across the country were ordered closed to limit the spread of the virus; they would not start to open until September 2021.

Says ASD’s Farhana Sultana, “We had been able to stop some of the marriages of the children who were under our project. But in the wake of the corona epidemic, many parents took their children home to their villages and then married them off. Which we did not even know about.” That is, until the schools reopened nearly two years later, and many of the girls failed to show up.

In the MJF study, Kurigram in northern Bangladesh had the most child marriages among the districts it looked into. Afroza Begum Alpana, who was Kurigram’s Union Women vice chairman, says, “When the school opened after lockdown, we saw that the number of girl students was very low. I relayed this matter to the committee. Then I went to several houses myself. Sadly, the parents had secretly given their daughters in marriage.”

Noor Alom, a rickshaw driver in Kurigram, admits that he had given his eighth-grade daughter away in marriage during the lockdown. “We are poor people,” he says. “In the pandemic lockdown situation, I go after financial problems. People don’t go anywhere in lockdown, no work is done. I can’t give the girl proper food. So, I found a suitable boy for my daughter and I married her off. I thought she would be happy.’’

Ministry of Women and Children Affairs Additional Secretary Mohiuddin Ahmed, however, strongly objects when told that the number of child marriages has been on the rise since the pandemic began and questions the data provided by rights groups and non-profit organizations.

Though classrooms have reopened, many girls have not returned to school; they have been secretly married off by their families. Some fear there are girls that have also been trafficked. (Photo used for illustrative purposes only.)

“Now local administration and local government administration have given priority to COVID,” he says. “The rest of the activities may have slipped to the bottom of the priority list. Maybe the possibility of violence against women and child marriage has increased. But it is difficult to say that it has increased.”

Difficulties in enforcing the law

No recent government research or study has been conducted on the country’s current child marriage situation. The Education Ministry recently said, however, that the government kept trying to reach most students through regular academic contact to prevent child marriage and possible dropout. Then again, that would have been possible only when schools were open.

Ahmed insists that the CMRA is being implemented “in a timely manner.” He says that Government Deputy Commissioners monitor district to district to prevent child marriages and that there is a helpline number for those who want to report and stop these from taking place “immediately.”

Some rights advocates concede that the pandemic did distract those in charge of keeping a close eye on minors so they wouldn’t be married off. But Fauzia Moslem says, “The government was not doing enough to stop child marriage. News of a child marriage will actually be the responsibility of the local councilor, chairman, or Upazila Nirbahi Officer.There was a demand for such monitoring. That was not done. It has become very urgent.”

Sources: Manusher Jonno Foundation, United Nations Children’s Fund

“By law we have fined some parents,” says Afroza Begum Alpana in Kurigram. “But these families are very poor. It is not possible for them to pay this fine. We have tried to bring the married girls back to school. But most of the girls moved to Dhaka City after marriage and so we could not find them.”

“According to the law, parents can be prosecuted or brought under punishment,” she continues. “But they are poor. They will not be able to pay the penalty. So for humanitarian reasons it was not possible to bring them under punishment. And in this way, even though there is a law, the law cannot be enforced, child marriage has increased.“

ASD’s Farhana Sultana meanwhile says, “There are many parents who do not know what is in the Child Marriage Act. Illiterate parents do not know about the law of child marriage in Bangladesh. So they are not afraid of the law.”

It could also well be that parents know of the law, but remain convinced they are well within their rights in deciding when their children will marry and with whom. Asked if he knows about CMRA, rickshaw driver Noor Alom snaps back, “What is the law of marriage again! I will marry my daughter to the boy of my choice. Why would the law punish me!”

The government is now looking at adding “Health Safety” in the secondary school curriculum next year to “raise awareness about child marriage,” as well as teach students about reproductive health. Some rights groups also report modest success in coaxing the in-laws of some married schoolgirls to resume their studies.

But that may not happen to Poppy, who now keeps house for her 28-year-old husband in the country’s capital, which is at least 10 hours away by car from her village and school.

She says that she knows there is a law that is supposed to prevent child marriages, but she is clueless what it says exactly.

“I told my parents, I have been talking about the law,” says Poppy. “But they do not believe me.” ●

Farhana Haque Nila is a Dhaka-based senior reporter with News Now Bangla. She writes about human rights violations, politics, and culture. She also works as a Freedom of Expression Monitoring Officer at Bangladesh and South Asia Article 19.