More than a decade has passed but Isuke Takakura remembers the horror of the Fukushima nuclear plant meltdown as clearly as if it was yesterday.

On March 11, 2011, he lost his house and several of his friends after a massive earthquake struck northeastern Japan and caused a tsunami. Experts would later say that it was actually the tsunami that damaged the nearby Fukushima Nuclear Plant and caused it to leak radioactive chemicals. Takakura and his wife had to leave their town with the rest of their community to avoid getting affected by the radiation from the plant.

Now 65 and retired from professional gardening, Takakura is among the returning residents of Fukushima. He and his wife, however, cannot return yet to Futaba town, which is just three kms from the damaged nuclear plant and where they had their home.

“Futaba is still out of bounds given the uncertainty of the decommissioning process,” he says. “The reason we are back to Fukushima is that we want to be close to our former homes.”

Futaba is the last of the towns affected by the 2011 triple disaster to have its evacuation order lifted, which means its residents can now return or visit there. But there are areas in the town that are not yet livable — such as that where Takakura’s house once stood.

A resigned Takakura says that while the devastation caused by the tsunami can be replaced with new construction, the nuclear disaster means nothing will be back to normal during his lifetime.

An undated photo of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, showing one of its chimneys. The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake of 2011 unleashed a devastating tsunami that damaged three of the plant’s four reactors.

“I am still living in a maze,” he says, describing the predicament he is in, which has left him feeling trapped. “Experts have predicted the decommissioning of the affected nuclear plant will take more than a hundred years. Survivors my age have given up returning to our hometowns that we always long for.”

As the 11th anniversary of the triple disaster approaches, Japan has declared Fukushima as being on the road to recovery. Indeed, only one-fifth of the radiation-affected 1,150 sq km area remains closed. Marine and farm products are now sold in the market based on regulations that Fukushima Governor Masao Uchibori describes as following “stringent safety regulations.”

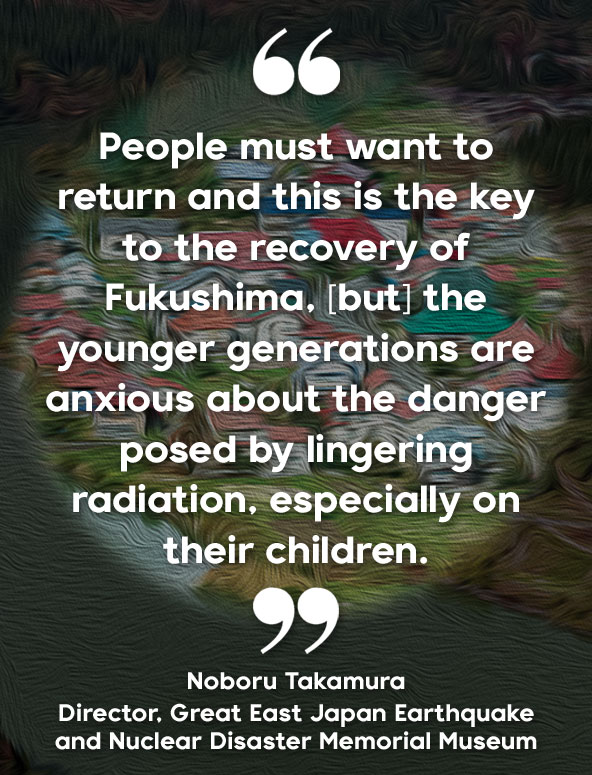

Professor Noboru Takamura, director of the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum, says that his post-disaster work in Fukushima has shown that stable recovery can only be achieved by rekindling the spirit of the community.

“People must want to return and this is the key to the recovery of Fukushima,” says Takamura, who is an expert on radiation treatment at Nagasaki University. His research has revealed that a strong sense of nostalgia is the biggest push in the return of senior citizens to the area. But he says that “the younger generations are anxious about the danger posed by lingering radiation, especially on their children.”

Governor Uchibori himself has admitted that the biggest challenge he faces is increasing the local population. Speaking to the press in February, he acknowledged that “many people are not returning despite the lifting of evacuation orders for most areas.”

“There are a host of issues to be overcome,” he added.

Disaster thrice over

The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake has been the strongest temblor yet in the country’s history. With a magnitude of as much as 9.9, it triggered a tsunami that reached a record high of 20 meters. The most affected were the coastal areas of Tohoku and southern Hokkaido. The waves broke and swept away houses located within five kms inland. In Fukushima Prefecture, which is part of Tohoku, three of the four reactors of Tokyo Electric Power Company or TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant were damaged by the tsunami, leading to radioactive releases at dangerous levels that spread over a radius of as far as 20 kms.

More than 470,000 people were forced to flee their homes because of the triple disaster, tearing communities apart. Ancient farming land and fishing spots were abandoned. Those who fled particularly because of radiation risk have been estimated to reach some 160,000.

As of December 2021, nearly 20,000 people have been confirmed to have died as a result of the triple disaster. But only one death — that of a Fukushima Daiichi plant worker — has been attributed to radiation exposure.

Some 2,500 people are still unaccounted for. The Reconstruction Agency, however, says that the total number of evacuees has been reduced to about 39,000.

Takakura lived alone in Tokyo for six years after the disaster. Then he found a new home for himself and his wife in Sukagawa, a city in Fukushima that is about 80 kms away from the damaged nuclear plant. Last year, the government built a school there to attract more returnees; several shops have also sprung up.

Takakura, however, spends much of his time planting trees around the neighborhood, although at least twice a month he meets up with other senior residents to talk about the past and the future.

“We need to maintain our past,” he says, “because we don’t want to forget and don’t want others to forget.”

He recalls that when the tsunami warning was issued that day 11 years ago, he had sprung into action as the headman of his community of about 6,500 people. Throughout that night, he made sure that everyone in his shocked neighborhood had escaped to the evacuation centers. Two days later, the radiation leaks were made public, and everyone in the community was ordered to leave the area altogether.

“Driving my family to safety, I was overcome with the thought of never being able to return again,” Takakura says. He adds that the latest blow to his fading hopes of being able to live in Futaba once more is the government’s decision … to dump processed contaminated wastewater into the Pacific Ocean.

“The decision is controversial,” he says. “I am terrified when I contemplate the future of this area.”

Radioactive wastewater

Anti-nuclear activists are campaigning against the contamination of marine life from radioactive wastewater. TEPCO says the decision is part of the ongoing decommissioning plan that involves clearing 1.5 million tons of treated water used to cool the fuel rods inside the damaged reactors. The wastewater will be diluted with at least 100 parts seawater near the plant and released through a pipeline in 2023.

The area of Tomioka in Fukushima was once designated as a “Difficult-to-return” zone. Many such zones have now been opened, with authorities hoping for the return of its residents.

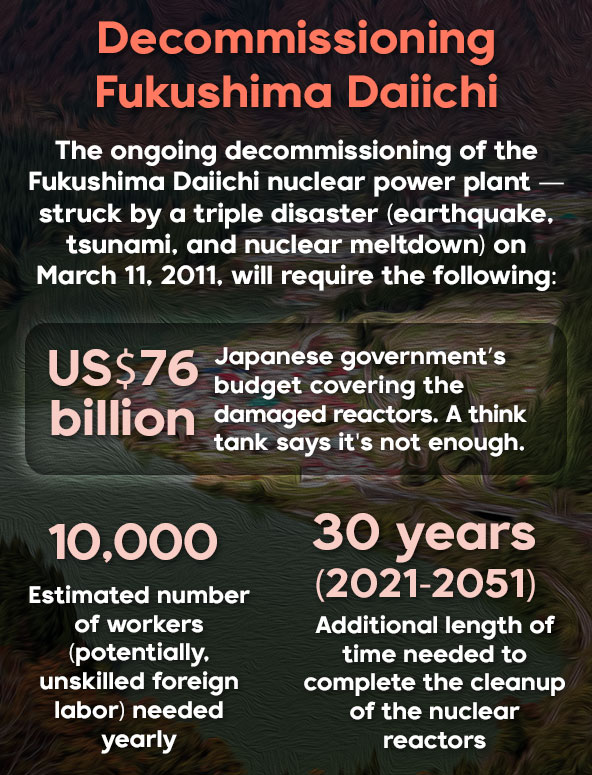

The think tank Japan Economic Research Center estimates that the cost for decommissioning the four damaged reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant will be more than the government’s budgeted US$76 billion. TEPCO meanwhile says that the cleanup of the reactors will take at least 30 more years.

Nuclear Regulation Authority Chairman Toyoshi Fuketa told the press in 2021 that he is concerned about a possible labor shortage, predicting more than 10,000 workers a year will be needed, with about a third assigned to managing the radioactive water. In 2019, TEPCO told the financial daily Nikkei that it intended to hire workers under Japan’s policy to permit the employment of more unskilled foreign labor.

But a spokesperson for the Workers Exposed to Radiation, a union formed soon after the Fukushima nuclear reactor disaster, says that the task would be dangerous for workers. The spokesperson, who declined to be identified, explains, “There is a risk of radiation among workers, who are hired by subcontractors and are exposed to long hours of work in the reactors. We are fighting for better conditions.”

Decommissioning also involves other jobs that are longer-term and which seem to be the reason why a few young families are settling down in Fukushima. Notably, these families are not all former residents of the prefecture. And while local government officials believe a major draw for returnees is the ongoing decontamination effort to remove radiation-affected topsoil in the formerly closed areas, it could well be that the people who would be attracted are those thinking that the activity will translate into jobs. There is no telling as well how long they will stay; according to Professor Takamura, such work usually ends after three years.

Questions about recovery

Figures compiled by the Fukushima Prefecture show that there were 62,000 people who left the area to live in other parts of Japan. This February, the return rate reached just 38,000, with the majority made up of senior citizens like Takakura. In a survey conducted in December 2021 among former Futaba residents, only 11.3 percent said they would return.

“People are questioning the concept of recovery as promoted by the government,” says scientist Hideyuki Ban of the Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center, a leading grassroots organization in Japan’s anti-nuclear industry movement. “They are more aware of the deeper threats of radiation and will continue to be vigilant.”

Ban says that the ongoing decontamination and decommissioning programs are severely limited. For example, he says, large swaths of forest surrounding residential areas have remained untouched since the disaster. He also points to the mounting contaminated debris stored in thousands of containers and the lack of workers as major concerns that contribute to public distrust of the government’s guarantees of safety.

High school teacher Hirofumi Hayashi who is stationed in a newly opened school in Hirono, a town just outside Futaba, says that his classrooms have around 30 students. The school is a merger of three schools in the area — a telling sign of the uphill struggle facing local governments keen to lure back former residents.

But Hayashi also observes, “As the anniversary of the accident approaches, I find the debate among survivors turning inward rather than demanding officials to change. People are keen to get on with their lives that are dependent on TEPCO-related jobs and government support.”

Nuclear physics professor Yoichi Tao, however, is not among the people described by Hayashi, who relocated to Iitatemura in Fukushima after it was declared decontaminated in 2017. Three years earlier, the Resurrection Fukushima Project, which he had initiated “to help rebuild lives and reconstruct agriculture-centered industries” in the prefecture, was formally recognized as a non-profit.

The Project has since attracted more helping hands and now includes corporate members. These days the 79-year-old Tao works as a volunteer to help local residents rebuild the ecosystem through the sharing of information and collaborative projects.

“Sustainable recovery is dependent on bringing back life through empathy and collaboration between people,” says Tao, whose supporters come from all over Japan. “Decontamination is not the answer.” ●

Suvendrini Kakuchi is a Sri Lankan journalist based in Japan, with a career that spans almost three decades. She focuses on development issues and Japan-Asia relations.