Experts say the Japanese economy is starting to recover from the slump it suffered because of the pandemic. However, Japanese women, in particular, will still feel its negative impact for far longer. The word “shecession” has been coined to refer to “an economic downturn where job and income losses are affecting women more than men.” This is the situation in Japan, where a growing number of women are falling into poverty due to the current health crisis.

Indications are more women have lost their jobs than men in Japan during the pandemic. This in turn has led to more women becoming homeless. Indeed, one of the news stories that shocked the nation last year involved a woman who had been rendered homeless after she lost her job at a supermarket. As she sat alone at a bus stop one night in December 2020, a man inexplicably hit her in the head with a bag full of rocks, killing her.

Then again, many of the women who still have shelter have not necessarily been luckier; according to some social workers, many of those who have been forced to stay at home with their family have become victims of domestic abuse.

“COVID-19 has exposed the underlying brutality of vast gender disparity in Japan,” comments Ren Onishi, head of the Moyai Support Center for Independent Living in Tokyo. “The sad situation faced by women today can be traced to the lack of political will and public negligence.”

In the 2021 Global Gender Gap Report by the World Economic Forum, Japan was at the 121st place out of 156 countries; it ranked lowest among the Group of Seven. The think tank pointed out that Japanese women are employed in just 14.7 percent of senior roles as judged by its economic participation index, despite 72 percent of the country’s female population being in the labor force. Women are also on the losing end of Japan’s notorious gender-wage gap. National Tax Agency data show that men earn an average of JPY 5.32 million (US$46,300) a year, while women earn only an average of JPY 2.93 million (US$25,600).

COVID-19 has exposed the vast gender disparity in Japan. The pandemic has tipped women into joblessness and extreme poverty.

Sixty percent of the female workforce, especially women with families, are employed only part-time. Women thus make up two-thirds of Japan’s non-regular workers, a sector that is facing the worst outcomes from the pandemic. In 2020, the government reported the loss of 750,000 jobs in this category, the highest in 11 years.

The average annual income for part-time workers is less than JPY 2 million (US$17,400). Surveys have shown that covering rent payment is their highest expenditure. The average monthly rent for a small apartment (20 to 40 sqm) nationwide is about JPY70,000 (US$609), excluding utilities; in central Tokyo, the average rent for similarly sized apartments is around JPY 100,000 (US$870) a month.

Down and out of a home

Grassroots groups providing food for free to Japan’s homeless communities have observed that since the start of the pandemic last year, there has been a sharp increase in women — some with children — lining up for their takeaway lunch boxes. Onishi says that at Moyai, which supports the homeless and the underprivileged, they have increased their number of free meals from 80 a day to 400, 20 percent of which are reserved for women.

Many women have now also taken to living in internet cafes or parks. Just recently, a woman in her 40s told a Japanese TV reporter that, after she lost her job six months ago, she was kicked out of her apartment because she could not pay the rent. “My application for social benefit was also rejected when I could not provide a permanent address,” said the woman who was not named by the TV network.

More often than not, struggling Japanese women are reluctant to even consider welfare programs because of the social stigma attached to the act of availing of such programs. Many are also discouraged by the maze of bureaucratic regulations that prevent them from successfully entering welfare programs.

There is the phenomenon of “hidden female poverty” as well. This is when women who have no money of their own live with relatives or their spouses. Despite their obvious lack of financial resources, they fall through the official social safety nets simply because they have a place to live.

“The Japanese postwar miraculous economic growth was based on a structure designed to support national growth rather than individual freedom,” says Masami Iwata, professor emeritus at Japan Women’s University. That goal, she says, has been strengthened by laws and regulations enacted by conservative male politicians and bureaucrats supporting a patriarchal society in which women are valued as unpaid domestic labor.

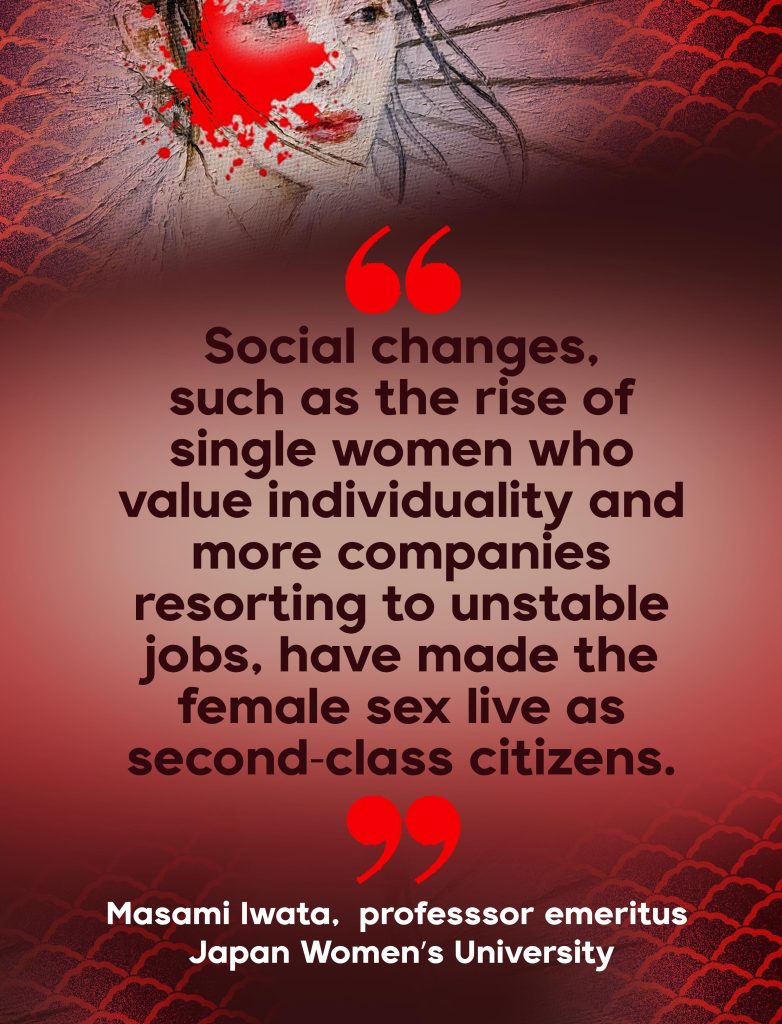

“The ticket for women to be economically stable was to marry a rich husband,” Iwata remarks. “But social changes, such as the rise of single women who value individuality and more companies resorting to unstable jobs, have made the female sex live as second-class citizens.”

That second-class citizenship includes the inability to own a home. Data based on the Household Economic Survey of more than 2,200 women in 2004 indicated that only 10 percent of them owned homes. There is little evidence that the situation has since improved for women.

According to Iwata, the low figure shows the importance of providing rent support for women based on their deprivation situation. It also shows how the country’s laws and bank rules have been working against women.

For instance, mortgages in Japan are overwhelmingly in the names of the husbands who hold full-time jobs and are the breadwinners. Obtaining bank loans are difficult for wives who are homemakers or hold only part-time jobs. Moreover, archaic laws permit a woman legal access to the family home only after the death of her spouse, or after they have lived together for a minimum of 20 years.

The rise in domestic abuse

Iwata is now pushing for reforms to pressure the government to develop a deprivation index for low-income women. She also says, “Public housing for abused women must be boosted so they can have a stable life. Support must also include individual income and education.”

In truth, the current pandemic has revealed that many Japanese women are having to endure physical abuse at home. Reiko Masai, head of Women’s Net Kobe, says that two-thirds of the 700 telephone calls her office received in 2021 were from women who wanted to leave their male partners. She recounts that one woman has told her of increasing violence from her husband who is now working from home. Masai says that the woman plans to escape once she received money from a new government relief program.

“The woman will finally be able to move into a cheap place temporarily when the government deposits JPY 100,000 each for her four young children,” says Masai.

Masai has won awards for her humanitarian work after the 1995 earthquake that hit Kobe, a bustling port city in western Japan. That disaster saw a spike in domestic violence that was related to more than 10,000 women losing their jobs and becoming dependent on their male partners.

With more Japanese women than men losing their jobs, some women lose the roofs over their heads and face an uncertain future.

After more than a decade of patient lobbying, Masai says that she has finally succeeded in gaining a mixed grant — public and private funds — for JPY 90 million (US$783,000) to construct a new shelter that will house 50 families, all headed by women. She is excited about the plan that is based on a new concept of collective living.

“The shelter will be a place for women to develop independence and self-respect,” Masai says. “Their children will be able to share living space and families will care for each other.”

“Finally we will be able to change the image of having only cheap, poor-quality housing for abused women,” she adds. “Stable housing provides them more mental care to turn around their lives and become part of society again, but this time as equal to everybody else.” ●

Suvendrini Kakuchi, a Sri Lankan journalist based in Japan, has a career that spans almost three decades. She focuses on development issues and Japan-Asia relations.