|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Haroon Janjua and Harun ur Rashid

This story was made possible through the support of the Pulitzer Center.

Clothed entirely in pink, the tall teenager looked out of place in the busy Hatirjheel police station in the heart of Dhaka. Ayesha, however, was there to do an important task: to submit her testimony about the gang that had tricked her into sex work across the border with promises of TikTok stardom.

Ayesha — who, like the other human-trafficking survivors in this story, is referred to using a pseudonym — had lost her job at a small fabric shop earlier this year because of the pandemic. At the time, she had also started dating Rifadul Islam, who had been introduced to her by a mutual friend. She even went to three TikTok hangout parties with the 26-year-old Islam, who used the handle “TikTokHridoy” on the social-media app.

“He had promised to make me a TikTok star in some foreign countries,” 18-year-old Ayesha told Asia Democracy Chronicles. She said that Islam, who had more than 71,000 followers on TikTok before his account was deleted, invited her last February to go with him to a TikTok party in Kushtia, a southwestern Bangladeshi city some 132 kms from Dhaka.

“I was not aware that I was being lured by the gang of traffickers using TikTok as a trap,” she said.

Human traffickers lure their victims with promises of social-media fame and a lucrative income.

An impoverished nation of some 167 million people, Bangladesh has long been notorious for being a human-trafficking hub. Thousands of Bangladeshis are believed to be trafficked each year, with many ending up in some form of labor or sex work in places as far as Turkey, Italy, and Germany. Next-door neighbor India is also a popular destination for trafficked Bangladeshis, many of whom are women and girls. Some studies indicate that as many as 50,000 Bangladeshi women and girls are trafficked into India each year. But as Muhammad Tariq Ul Islam, country director at the UK-based charity organization Justice and Care, observed, “Human trafficking is a clandestine offense. So many cases are happening beyond our knowledge.”

These days, police and activists say that traffickers are increasingly using social media to trap vulnerable teens like Ayesha, as well as college-age women and even housewives so they could later be used for sex work. In some cases like Ayesha’s, they are lured with promises of social-media stardom that could mean a lucrative income for them. In other instances, apps like Facebook and WhatsApp become the means for traffickers to build fake relationships with their targets and earn their trust. (According to the statistics site dataportal.com, Bangladesh had already racked about 45 million social-media users as of January 2021, up by 25 percent from the previous year.)

Trafficked across the border

Police say that in the last five years, the gang that tricked Ayesha had trafficked at least 1,500 women and girls into India from a porous border with Bangladesh at Satkhira district. Its operations were finally exposed last May by a 22-year-old Bangladeshi who had escaped its clutches in India and had made her way back to Dhaka. A video of her being abused went viral after her escape, triggering a manhunt for the gang by both Bangladeshi and Indian authorities.

“This is a new trend of crossing the border, women trafficking by using social media apps,” Bangladesh Home Minister Assaduzaman Khan Kamal told ADC. “(It’s) alarming, and we need to find new laws and investigation to tackle it. (But) we have a 4,000-km border with India, which (poses) difficulties.”

Bangladesh Deputy Police Commissioner Muhammad Shohidullah, for his part, said that powerful people are involved in human trafficking in both Bangladesh and India. He added that Bangladesh has had laws addressing the issue since 2012, but that prosecuting and convicting perpetrators have always faced obstacles. Bangladesh police data, for instance, show that between 2017 and 2018, a total of 2,904 individuals were arrested for human trafficking; during the same period, only nine were convicted of the crime.

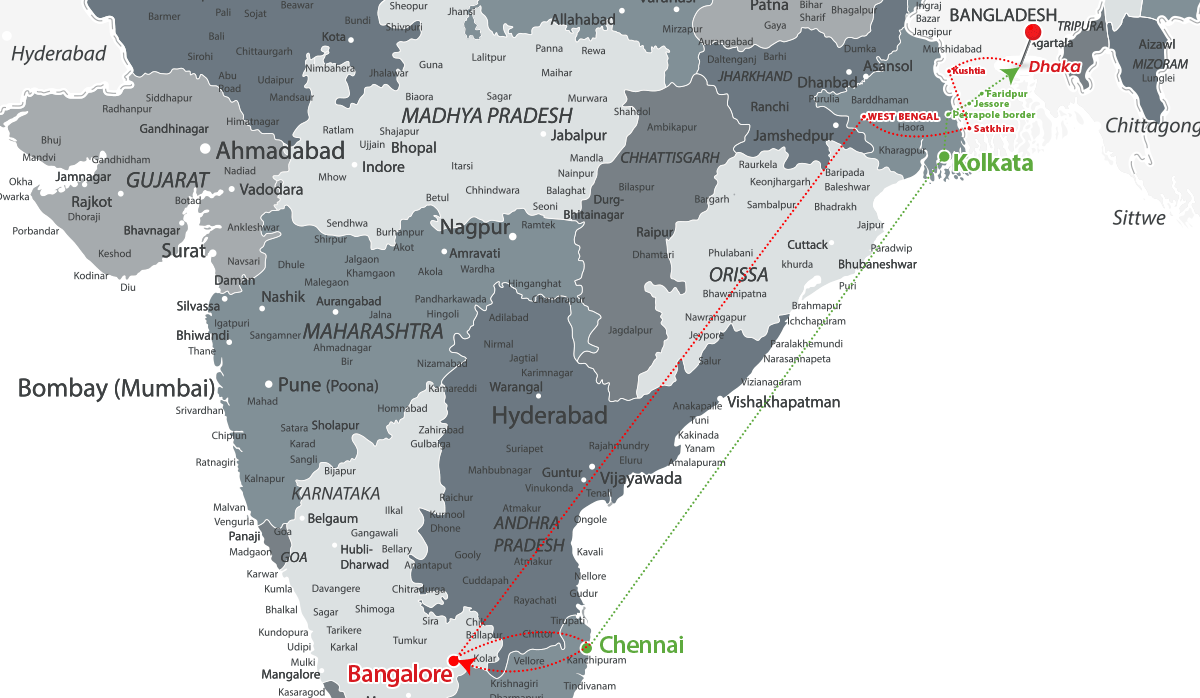

A recent study by the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee migration department on cross-border human trafficking says that the hotspots for the crime in the country are Dhaka, Jessore, Khulna, Sathkhira, Chittagong, Cox’s Bazaar, Barisal, Narshingdi, Manikgong, Jamalpur, Rajbari, Narail, and Hibigong. The Indian state of West Bengal is the foremost immediate destination for trafficked Bangladeshis, since it shares 2,250 kms of land border and 259 kms riverine border with Bangladesh.

Traffickers also operate their sex businesses through selected hotels, massage parlors, and rented houses in south Indian cities such as Hyderabad, Chennai, and Kerala.

Aside from its Indian operations, Islam’s gang had a presence in the Middle East as well. On May 27, Islam was finally caught by Indian police, along with five of his cohorts, in the Indian southern city of Bangalore, where they are currently detained. Two of those arrested there are women. They are all being prosecuted in India but may be brought back to Bangladesh to face more charges.

Dhaka Police Additional Deputy Commissioner Hafiz Al Farooq, who is investigating the trafficking gang, told ADC that so far six cases against the group have been filed with the Hatirjheel police station. Of the 16 accused who have been arrested, 11 have confessed their crimes, he said. Ferdous Niger, the coordinator of Bangladesh National Lawyers Women’s Association, noted, though, that “police are still investigating the cases and have not filed the (charges) before the court.”

Young girls are taken far from home after being lured by traffickers. Ayesha herself was brought to Bangalore and Chennai in India (red dotted lines), where she was raped by several men. She eventually escaped and made the arduous trip back home to Dhaka (green dotted lines).

A dangerous detour

For sure, becoming a sex slave, and in another country at that, had never crossed Ayesha’s mind. She said that at first, she had been reluctant to accompany Islam to a hangout party being held so far away from Dhaka. But, she said, he had “pleaded” that it was for his TikTok career. Instead of getting on the bus for Kushtia, however, Islam had them take one headed for the border town of Satkhira. Recounted Ayesha, “He told me we mistakenly took the wrong bus and I didn’t doubt him.”

By the time they reached Satkhira it was already night, and they had to stay in a private home where another girl, Neha, was waiting.

“The next day we crossed the border and entered into India’s West Bengal region,” said Ayesha. “Hridoy took selfies for TikTok and called it a nice moment.”

By then, the teener had realized that she was being trafficked. Recalled Ayesha, “When I threatened them that I will go to the police, they said, ‘You have no visa and passport. If police come to know about you, you will go behind the bars for 20 years.’”

That night, in North 24 Parganas District, she and Neha were raped — Ayesha by two men, Neha by three. Ayesha was later separated from Neha and kept with two other girls, Aaliya and Khalida, in Bangalore. According to Ayesha, both girls had already been kept captive by the gang for more than a year by the time she met them.

When Ayesha was told she was going to be taken next to a hotel in Chennai, she tried to resist, which resulted in her being tortured. A video was also taken of her being raped again.

“On March 12, they shifted me to OYO hotel Chennai, and on the first day I was forced to do sex with 19 men,” said Ayesha. “That night, I became seriously ill. The hotel staff said to me in Hindi that every day I have to do sex work with 30 men. I cried and pleaded with the hotel staff to free me.”

Escaping from horror

Ayesha ended up bleeding, forcing Hridoy to take her back to Bangalore. She says that Islam tried to rape her roommate Nadia there one morning and that when she came to Nadia’s defense, Islam hit her on the head with a wine bottle. Ayesha had to have four stitches on her head afterward.

Ayesha, 18, (left) survived a harrowing experience at the hands of human traffickers. Ferdous Niger (right), the coordinator of the Bangladesh National Lawyers Women’s Association, is helping locate and bring the other girls home. (Photos by Sazzad Hossain)

“I was making plans in my mind to escape,” said Ayesha, “and when Nadia escaped from the hotel one night and Sumayya from the massage parlor, I also tried escaping the next day. But I was caught.”

Her captors then started monitoring her more strictly. But because her poor physical condition made her unable to do sex work, they decided to transfer her to Chennai. Ayesha said, “After a few days, I escaped from there. I went to Kolkata by train and the same day I crossed the Indian border Petrapole by bus illegally through an agent by paying INR 500 (about US$7). I did not stay in any hotel. All I wanted was to leave India at the earliest before they followed me.”

Ayesha finally reached Dhaka on May 7; she had spent some three months in sex slavery in India. She is now back home with her family, but she has yet to seek help from anti-trafficking groups, for fear of being labeled a sex worker.

Sumayya apparently also made it back to Bangladesh. But Nadia remains in India, although she is now safe at a government shelter in Kolkata. According to her father, who is a rickshaw driver, Nadia is a 9th grader.

“On March 17 my daughter went out for 30 minutes, she told me she had urgent work,” he said. “But when I called her on mobile, it was switched off.”

“I came to know that some girls were trafficked by Hridoy,” he added. “When I showed them her photographs, they confirmed that they had met her and that she was in (Bangalore).”

He said that Indian police had rescued his daughter, but that they had demanded BDT 100,000 (about US$1,100) to release her.

“I am trying to bring Nadia back,” said Niger, who is representing the trafficked girls in their legal battle. “She is in trauma and has repeatedly requested me to bring her back to Dhaka. We are communicating with the Indian government through our Foreign Ministry, but it’s not so easy.” ●

Haroon Janjua is an award-winning journalist covering South Asia. Based in Islamabad, Pakistan, he is a 2021 Pulitzer Center grantee. He has also received the 2015 United Nations Correspondents Association Award, the 2015 IE Business School Prize for best journalistic work on Asian Economy, and the 2015 Global Media Award from the Population Institute in Washington D.C.

Harun ur Rashid is a multimedia journalist based in Dhaka, Bangladesh, who works for Deutsche Welle (DW) TV and Radio.