In Jamunipur, a hamlet in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, Maina Devi nurses an infant. The baby’s twin sleeps by her side and she keeps a watchful eye on her older twin set, still toddlers, who are playing nearby.

“I wanted to be sterilized when my second set of twins was born,” the 25-year-old mother says. “But my family said life in our village is too uncertain for such things.”

Village health care worker Savitri Devi commiserates. “I was there when she gave birth to her twins and asked to have her tubes tied,” she says. “But what could I do when her husband objected? One infant died at birth in our village this year, and that has spooked everyone.”

Other women, mostly illiterate agricultural laborers and marginal farmers, join the conversation. The consensus is that they would be happy to be sterilized or go on a contraceptive pill after having two children — but the decision is not theirs to make. Says Maina Devi: “For most women like me, the decision on how many children to have and when to get sterilized lies with our husbands and in-laws. I can only pray I don’t get pregnant again.”

Testimonies like Maina Devi’s abound in the hinterlands of India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh. But a recent move by the state to control its population number may not necessarily be the solution to the women’s problems.

Last July 11 — World Population Day — Uttar Pradesh State Law Commission released the draft Uttar Pradesh Population (Control, Stabilization, and Welfare) Bill, 2021, to promote two-child families in the state. A slew of incentives and disincentives have been laid out in the bill. Violators of the two-child norm will be debarred from contesting local body elections, applying to government jobs, or receiving any government subsidy. On the other hand, couples below the poverty line who comply by voluntarily undergoing sterilization after their second child will receive monetary benefits.

The northeastern state of Assam announced plans for a similar policy at the same time. Gujarat, Lakshadweep, and Uttarakhand are now reportedly considering similar legislation.

Women in the Bhadohi district in Uttar Pradesh are briefed on the benefits of small families. But for women like Maina Devi (right), who has two sets of twins, it’s not up to her — it’s her husband and in-laws who decide. (Photo by Geetanjali Krishna)

These policy changes, all proposed in states where the ruling rightist Bharatiya Janata Party is in power, have been seen by some as politically motivated and an appeal to the popular but unsubstantiated belief that Muslim family sizes are much larger than those of Hindus, putting them at risk of becoming a numerical minority. Coming around the same time as China has relaxed its two-child limit in the face of a rapid decline in its working-age population, the proposed policies have been widely criticized.

What population explosion?

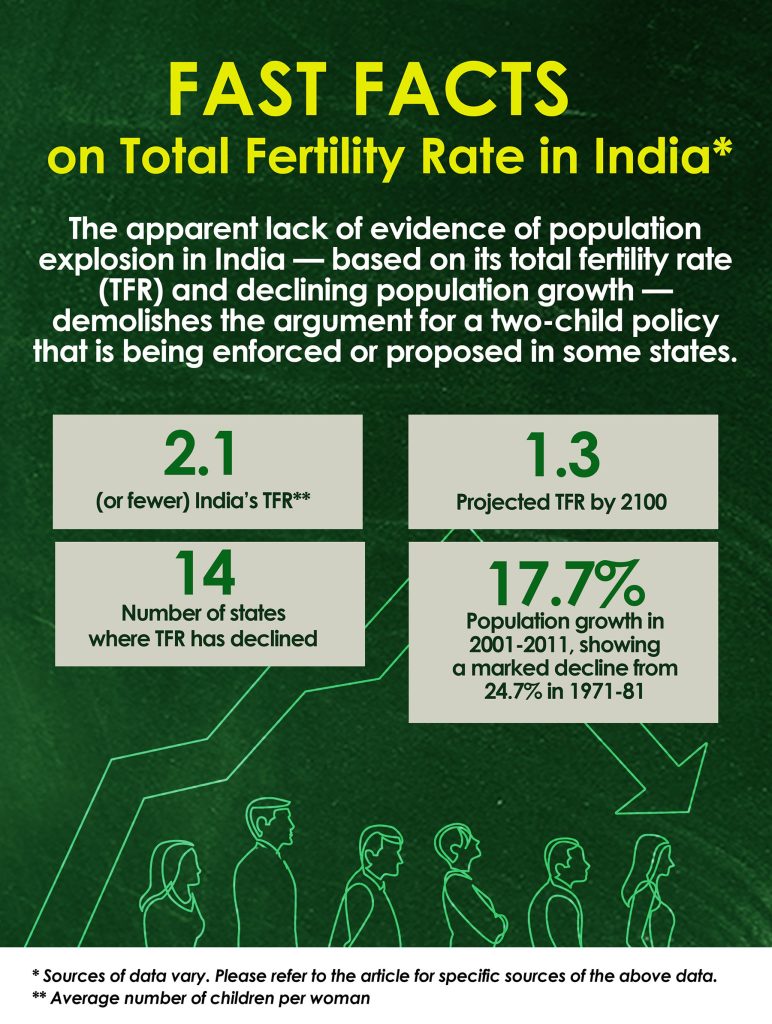

With more than 1.39 billion people, India is second only to China in terms of population size. But Poonam Muttreja, executive director of the non-profit Population Foundation of India, points out, “There is no evidence of population explosion in the country as India’s decadal population growth rate, i.e., the rate at which population grows in one decade, has been declining from 24.7 percent during 1971-81, to 23.9 percent in 1981-91, 21.5 percent in 1991-2001 and to 17.7 percent in 2001-2011.”

The country’s Total Fertility Rate or TFR (average of the total number of births per female) is 2.2. The 2020 National Family Health Survey indicates that India’s TFR has decreased in 14 out of 17 states and is now at 2.1 or fewer children. Demographers predict a further drop in TFR in the coming years. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, an independent population research center at the University of Washington, has projected that India’s TFR will drop to 1.3 by 2100 if present trends prevail.

According to a global study by The Lancet, India will stabilize its population — meaning its birth and death rates balance each other out — 12 years earlier than expected.

Social worker Pushplata Maurya observes that women in rural Uttar Pradesh are limited by lack of access to reproductive choices, even as they suffer from high infant mortality rates. She asserts, “This — not a policy that punishes women for having babies when contraception is not in their control — is what the government needs to improve to bring down the TFR in the area.”

According to the 2018 Sample Registration System (SRS) survey, UP’s infant mortality rate is 43 per 1,000 births (46 for rural areas); the national figure is 32. “The only social security people have is their sons,” says Maurya, explaining the preference for boys here. “They can’t risk losing an only son to a childhood disease.”

She describes the lack of water, sanitation, and public health infrastructure in the 20-odd villages she visits regularly in UP. “Beejapur, a small hamlet in Bhadohi that I regularly visit, is the worst!” she says, recalling that it does not have a single working toilet. “Villagers drink from a well so contaminated that they strain out insects before consumption.”

Local accredited social health activists or ASHAs and anganwadi (community health care) workers are responsible for ensuring institutional deliveries and vaccinations. But the COVID-19 pandemic has shifted their focus. In the meantime, Anita Devi, an ASHA from Beejapur, says, “Children fall sick very often here. We tell women about the benefits of smaller families, but with the uncertainty of life here, what can they do?”

Access to health, especially reproductive health services, is another issue, not just in Bhadohi, but in most of rural UP. In Jamunipur, for example, the nearest hospital is eight kilometers away; no doctor visits the village, and family planning advice, support during pregnancy, and immunization of children rest on the shoulders of the village’s two health care workers.

Education trumps punitive measures

Not far from Jamunipur, in Khamaria — also in Bhadohi district — Najma Begum is expecting her second child. Her firstborn is not even a year old. Begum is not alone. According to SRS 2018, 1.4 percent of second births in Uttar Pradesh are within 10 to 12 months of the first birth (the all-India figure is 1.6). Lack of spacing between two children indicates a lack of access to information and contraception, a fact that Najma echoes. She says, “I don’t go out of my house alone. Even if I wanted to use contraception, I won’t know where to get it and how to use it!”

Now comes a punitive two-child rule that could lead to more problems and may further disempower women instead of giving them choice and agency to live their lives.

“There is evidence that population-control measures can lead to negative consequences such as increases in sex-selective practices and unsafe abortions, especially given the strong son-preference in the country,” says Muttreja of the Population Foundation of India. “Haryana and Punjab’s implementation of a two-child policy provides us with strong evidence of the unintended consequences of such a policy: a highly skewed sex ratio.”

India and China already have the largest number of “missing girls,” or missing female births lost to sex-selective abortions. Muttreja fears that this practice would increase if policies punishing couples for having large families came into play.

Punitive measures like electoral restrictions for couples with more than two children often affect women more than they do men. Women will not be able to find political voices if the law disallows them from standing for elections. Moreover, such measures are a threat to informed choice as this would no longer be voluntary.

The impact of similar policies elsewhere is instructive. In 1980, the Chinese government imposed a strict one-child policy. In 2015, it was forced to raise the birth limit to two, to reverse declining birth rates and rejuvenate an aging population. Then in May 2021, the government capped the permitted number of offspring at three. A study in The Lancet forecasts that in China, with a projected 48 percent decline in population, the ratio of the population over 80 to the population under 15 will increase further. With all other factors remaining the same, the decline in the population of working adults alone will reduce GDP growth rates.

Similar policy reversals have been observed closer to home. Four of the 12 Indian states that have implemented different versions of the two-child policy have revoked it over lack of any evidence of impact. Others like Bihar have hastened the reductions in TFR without enforcing a two-child norm.

Meanwhile, the SRS 2018 shows that as women’s literacy improves, their TFR decreases. For example, Kerala and Himachal Pradesh have female literacy rates of 99.5 and 98.8 percent and TFRs of 1.7 and 1.6, respectively. In contrast, Bihar, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh have female literacy rates of 76.5, 77.4, and 79.7 percent, and TFRs of 3.2, 2.5, and 2.7, respectively. Globally as well, countries like Sri Lanka, Indonesia, and Bangladesh that have focused on improving female literacy levels have had the most successful family planning programs.

Local anganwadi (community health care) workers Anita (left) and Ranjana Devi say the pandemic has made their job in reproductive health even more challenging. (Photo by Geetanjali Krishna)

Says Muttreja: “We need to ensure that girls complete at least 10 years of schooling. Comprehensive reproductive sexual health education should be made mandatory for in-school and out-of-school children.”

India’s population peak, with two-thirds of the country’s population being under 35 years today, is yet to come. By 2027, India is expected to overtake China to become the most populous country in the world, and its population is expected to take two decades to stabilize.

“In the meantime, states need to view their population as an asset for development rather than a liability,” Muttreja says. “We should abandon all incentives and disincentives and instead enable couples to make their own positive reproductive choice.” ●

Geetanjali Krishna is a contributing editor with Business Standard and is the co-founder of The India Story Agency, which specializes in telling human interest, environmental, and social affairs stories and case studies from South Asia to the world. She has written for Times, The British Medical Journal, the BBC, The Third Pole, and Business Standard.