For almost two decades, international organizations had been a sustained presence in Afghanistan and engaged in all sorts of media-development projects across the country.

But with the uncertainty now confronting many of the journalists and media workers remaining in Afghanistan, the media development and engagement blueprint brought over by international groups to the country has come under scrutiny.

“It is really a sad situation,” says Salma*, a researcher and a human rights activist who works with Afghan media groups. “One day you have the free will to seek out the truth, next day you are not even sure what to wear and whether what is on you would land you in jail or worse.”

In mid-August, after sweeping through most of the country, the hardline Taliban took control of Kabul. It has since declared itself in control of the entire nation and has set up an interim government.

But the country remains in chaos, with the lack of credible information a significant part of the problem. Indeed, fear of the Taliban has practically wiped out any attempts to have unbiased reporting. Notes Abas*, a journalist and media rights advocate: “In Afghanistan, the message, both in overt mainstream and covert social media, is by and large pro-Taliban. Social media does include some dissent, but if not total, this is a 95 percent takeover of the Afghan airwaves and digital sphere since August.”

He also observes that while the pullout of the United States and its allies was swift, the exodus of media rights groups and their officials from Afghanistan was even swifter. Most of the international media rights workers have left, says Abas, and with their departure, many of the institutions they helped build have crumbled.

Abas grew up enjoying a relative degree of freedom despite frequent attacks and violence instigated by extremists in Kabul and elsewhere. He worked as a journalist and then as a media advocacy professional with one of the many international media rights bodies that worked in Afghanistan. He studied in the West and traveled widely. He particularly loved traveling in South Asia, where our paths crossed on several occasions.

He is grateful for all those freedoms, Abas says. He adds, “When the government that was backed by the U.S. was in office, we could at least talk freely, write freely and even travel freely.”

But he bemoans that with the departure of the United States and its allies, Afghans remaining in the country do not seem keen to fight as a society for those rights he still holds dear. “There were so many international agencies and personnel here, but everything depended on them,” says Abas. “We have failed in the task of nation building because the citizens — at least most of them — are weak as they were before.”

Myanmar’s story

This is in stark contrast to what has been happening in Myanmar, where the people have been fighting back and refusing to accept the rule of the military. In February, Myanmar’s military had suddenly declared a coup, right before the newly elected parliament was supposed to be sworn in. It then detained the leaders of the National League for Democracy (NLD), which had won another landslide victory in the elections, and many of its supporters. What the military had not counted on, however, was the determination of the people of Myanmar to assert their right to choose their leaders.

Zaw, a journalist in Myanmar, says that Afghanistan and Myanmar present two outcomes of outside engagement and skills enhancements of media: In Afghanistan, the advent of a hardline regime has driven most of the media either out of the country or they are planning to flee. In Myanmar, even though there has been movement out of the country, a sizeable number of journalists remain in the country and continue to work.

Recent research by the Australia-based Judith Neilson Institute shows that since the February coup, media freedom has severely come under pressure in Myanmar and the onus has fallen mostly on citizen journalists. But Zaw sees this as a sign that at least some of the skills enhancements have seeped deep into the Myanmar community.

“That is where is the skills have passed on, there is a sizeable population that is tech-savvy to keep information getting out,” Zaw says. “It probably is a result of training, workshops on digital skill. Will that happen in Afghanistan?”

Abas is not sure. He points out that many journalists like him who have built up their skills are either now out of the country or waiting to get out because they are likely to be targeted by the Taliban if they stay.

Indeed, nine days after Western forces completely withdrew from Afghanistan on August 31, the Committee to Protect Journalists reported that 14 journalists had been detained and released within 48 hours. Six of the detained journalists were tortured. Footage later appeared online that showed two of them, Taqi Daryabi and Nematullah Naqdi, of the daily newspaper Etilaatroz, with red lesions from beatings.

Other footage available online showed a photographer being led away by Taliban fighters in Herat. According to the International Federation of Journalists, the harsh treatment of journalists in effect contravenes the very pledges made by the Taliban to be tolerant of dissent.

Asked if there is any possibility that an Afghan media community in exile could thrive, just as the Myanmar journalists who overseas did during the decades before the NLD was able to sit in government in 2016, Abas replies, “There is no history in Afghanistan of an impactful, large-scale journalism diaspora. But this year we have seen a high number of journalists and others leaving Afghanistan, and they have already become individual transmission points of information. At least in the short term that will continue. “

“Maybe they will form the nucleus,” he says, “but so far I have not heard of any organized campaign as such.”

Amid the atrocities committed by the military junta in Myanmar, many journalists remain in the country and continue to work. In Afghanistan, the advent of a hardline regime has driven most of the media out of the country while others are planning to flee.

The West as ‘nanny’

Safiullah Gul, a journalist and researcher based in Pakistan, is more pessimistic. “The Taliban has time, it can wait as long as it wants to run down any kind of opposition, homegrown or overseas,” he says. “We are in for a long period of attrition. What is happening right now in Afghanistan is not forceful suppression, but a tactic of subtle acquiescence of the Taliban way by Afghanistan.”

Gul also indicates that the West had made a fatal mistake of holding the hands of Afghans for too long and not ensuring that they would be able to fend for themselves down the road. He says that it has always been clear that extremism almost always had power within its reach in Afghanistan. Asserts Gul: “That should have alerted those working on rights issues, especially media-related issues, to think more deeply about the consequence of a pullout or even scaling down of Western presence.”

By comparison, the people of Myanmar had long been used to being left on their own to deal with a brutal junta. That was the case in the decades before the 2015 elections won by the NLD, and that seems to be the case as well now. In the meantime, its exiled community had developed media outfits that monitored developments back home and became beacons of information and hope for the people enduring the junta. These days, that exiled Myanmar media are taking where they left off years ago.

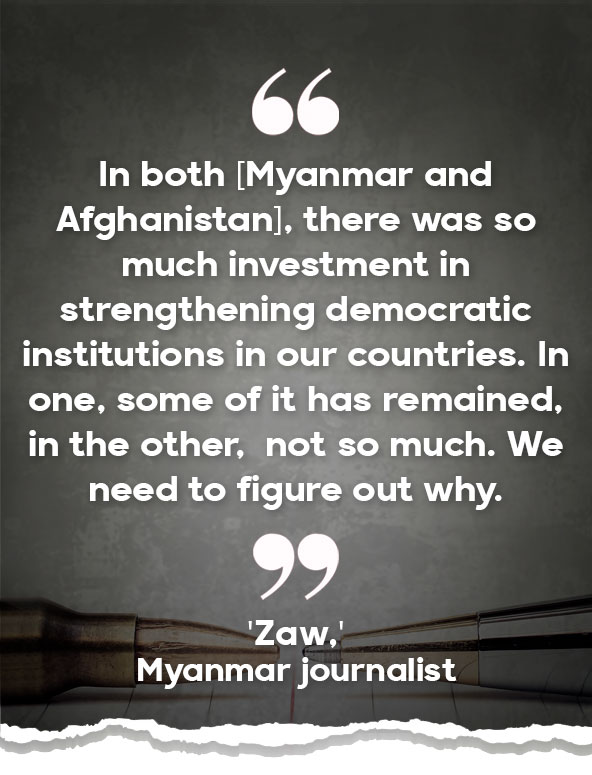

Zaw, who has been shifting residence frequently since the February coup due to security concerns, says that media development strategists should study Myanmar and Afghanistan closely.

“In both cases, there was so much investment in strengthening democratic institutions in our countries,” he says. “In one, some of it has remained, in the other, not so much. We need to figure out why.”

As the situation for the media in both Afghanistan and Myanmar continues to deteriorate, Zaw and Abas stress the importance of strengthening regional journalism networks. According to Zaw, regional networks based in Myanmar’s neighboring countries like India and Thailand were vital not only as close, easy-to-access, safe havens but also as means to build regional pressure.

In contrast, the lack of similar set-ups in South and Central Asia has come to harm those like Abas who are still trying to get out of Afghanistan. Humanitarian workers say that most of the nearby countries closed their borders as the U.S. pullout reached its final stages. One humanitarian worker says that besides Pakistan, the only other country willing to take Afghan passports from the member states of the South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) was the Maldives.

“For that too, we had to show a lot of money and the travelers would go to high-end resorts,” says the worker. “No option really.”

Gul believes that regional networks would probably be vital given the geopolitical changes in the region. He says that no one had taken the effort to analyze Afghanistan without the United States and its allies actively present in the country. Gul says, “It is a new ball game now, you have Pakistan, you have Iran, you have Russia, but don’t forget what China has become in the last 20 years.” Similarly, China’s diplomatic role has been and will be pivotal in Myanmar.

But Abas doesn’t want to wait around until these strategic policy shifts take place. In the last week of the U.S. pullout, he got on a bus and set out for the Kabul airport. He had a stamped visa and a seat waiting. But their bus was never able to navigate through the thousands trying to get inside the airport. Neither could they get through some of the checkpoints manned by armed fighters.

“Now, me and my family are at the mercy of whatever happens tomorrow,” Abas says through a patchy phone line. “We have no control. The airport may open, it may take two weeks, three weeks, or six months. Even then, will I be allowed to go? Where will I go?” ●

* Names have been changed for security reasons.

Amantha Perera is a Sri Lankan researcher at the School of Education and the Arts of the Central Queensland University, Australia. He is currently in the final stages of his master’s research project on the online trauma impact on journalism during the COVID-19 lockdowns.