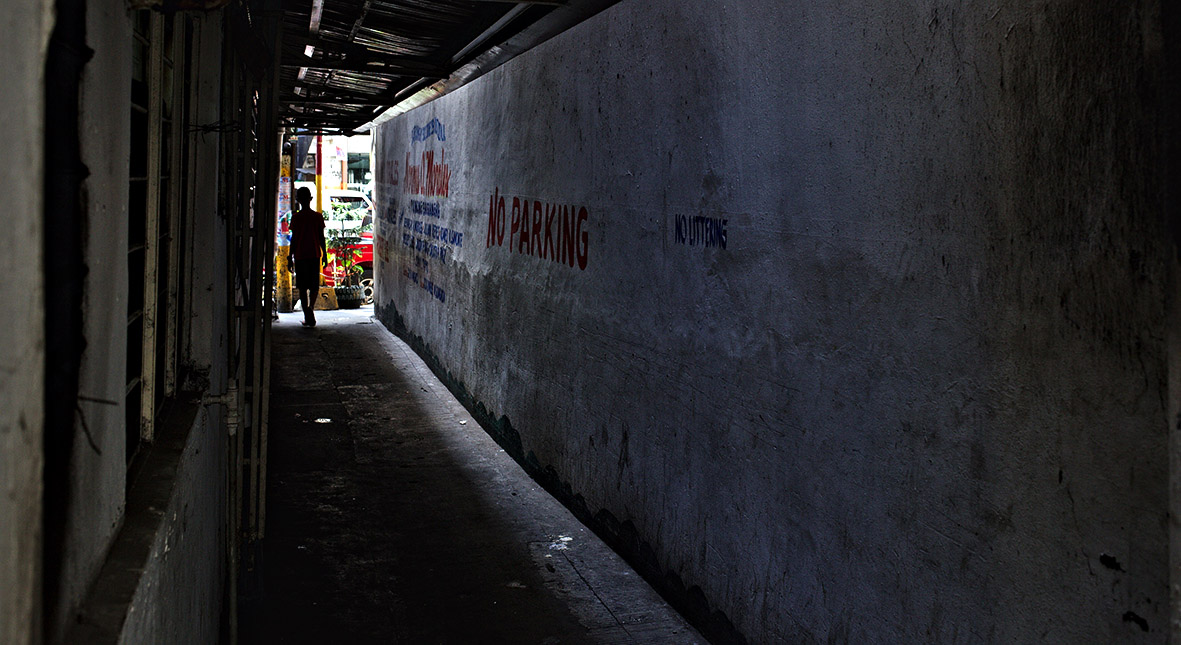

Exactly a week before he was killed on September 8, 2010, Philip Cabugao came to the aid of a friend who had been shot in the middle of a busy intersection in Tibungco, a district in Davao City in Southern Philippines. As Philip cradled the head of his dead friend, someone took a photo of them, his brother Victor told me. Seven days later, Philip, who worked as a public transport dispatcher, was himself shot once in the head a few steps from where his friend had died. He was just 23.

With the confidence of killers who know they operate with impunity, in broad daylight, the three assailants arrived on motorcycles and shot Philip in full view of bystanders. Victor said he rushed to his fallen brother, slumped by the roadside in front of a gasoline station, after someone alerted him. A few days later, Victor was told by a neighbor that he was now also a target of a shadowy band of killers known as the “Davao Death Squad.” This forced Victor to leave Davao City and move to Manila. “I was now being hunted,” Victor told Human Rights Watch in a 2012 interview. (The Cabugaos’ names have been changed for security reasons.)

The Philippines’s anti-drug campaign has targeted politicians on the “narco list” and teenage boys suspected of pushing drugs in the streets. The only change it has brought on is a rising body count — and an outraged citizenry.

On Sept. 15, the International Criminal Court in the Hague announced the opening of an investigation into crimes against humanity during the so-called “war on drugs” campaign in the Philippines. The ICC investigation is an important reckoning. It seeks to tackle the human rights catastrophe of the “war on drugs” by providing genuine accountability. It should bring hope to families of victims and all Filipinos concerned about human rights.

Rodrigo Duterte was mayor of Davao City at the height of the Davao Death Squad killings. These killings may prove very important for the ICC investigators, as two former death squad members are among the witnesses who are reportedly going to testify. In July 2013 alone, for example, Tambayan, a local children’s rights group, documented 19 killings. The majority of the death squad’s victims were poor Davaoeños who worked as laborers or tricycle drivers.

Many later killings under Duterte’s even bloodier presidency followed the pattern of the Davao City summary executions. Since 2016, thousands have died in Duterte’s “war on drugs,” with police and their agents routinely committing extrajudicial executions and, as the Human Rights Watch found in its investigations, planting evidence such as guns and illegal drugs on the bodies. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, in a June 2020 report, upheld these findings, adding that the government’s campaign “has led to serious human rights violations, reinforced by harmful rhetoric from high-level officials.”

The ICC’s Office of the Prosecutor reported that the Davao Death Squad killed 385 people between 2011 and 2015 alone. Nationwide, the “war on drugs” death toll ranges from 12,000 to 30,000, the ICC decision said.

The court’s jurisdiction starts from November 1, 2011, when the ICC’s Rome Statute became effective in the Philippines, until March 16, 2019, when the country’s withdrawal from the ICC became final. The court said it would investigate murders in Davao City that occurred between November 2011 and mid-2016, when Duterte was the city’s mayor, and throughout the Philippines between July 2016, after Duterte was elected president, and the March 2019 end date.

Mass organizations and families of the victims of drug war killings in the Philippines have been demanding justice, pinning their hopes on the International Criminal Court’s investigation into Duterte’s bloody drug crackdown.

Duterte continues to harness his high popularity in the polls as he ends his constitutionally mandated single term as president and seeks a new mandate as vice president, perhaps partly in the belief that this may insulate him from ICC prosecution. (Editor’s note: On Oct. 2, 2021, Duterte announced that he will no longer seek the vice presidency in next year’s election and will retire from politics.) Duterte has argued that the ICC’s action on the Philippines is a Western imposition and that the court has no jurisdiction in the country. These claims, however dubious, may shape the upcoming elections. In a country where human rights issues almost always take a back seat in elections to other less lofty considerations, interjecting the possible prosecution of a candidate by the ICC treads new ground, with an uncertain outcome.

By this single act of an independent, international body to investigate crimes against humanity, real inroads may finally be made into the impunity that has bedeviled the Philippines for decades. ●

Carlos Conde is a senior Philippines researcher at Human Rights Watch. He is a former journalist who reported on the Davao Death Squad killings for the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) and the New York Times, among other publications. This report was originally written by the author for the PCIJ, where it was published on Sept. 25, 2021. The content is the sole responsibility of the author and the publisher. Reprinted with permission.