Freelance journalist Rahul Samantha Hettiarachchi has gamed the science of unlocking information using Sri Lanka’s Right to Information (RTI) law. Since its inception in 2016, the law has helped Hettiarachchi access information that becomes material for his stories. And so after the country’s parliamentary elections were concluded in August last year, he went right to work and submitted several hundred RTI requests to various government agencies.

The information he was seeking were related to arrests made under provisions connected with COVID-19 restrictions during the run up to the elections. In all, he submitted 408 requests — 362 to regional medical offices and 46 to police stations.

A few days after he submitted the requests, Hettiarachchi received a phone call. The caller identified himself as an officer from the Vavuniya Police Station, some 380km north of Hettiarachchi’s base in Hambantota, in the deep south of the island. The caller asked the journalist why he was looking for details on COVID-19 restriction violations.

By then Hettiarachchi had used the RTI Act long enough to know that not only was he within his constitutional rights to seek such information, but that the law’s provisions on privacy had been violated; the police were not supposed to be aware of his requests. He rebuffed the caller and soon other media outlets picked up on the incident. There were no more veiled communications afterward.

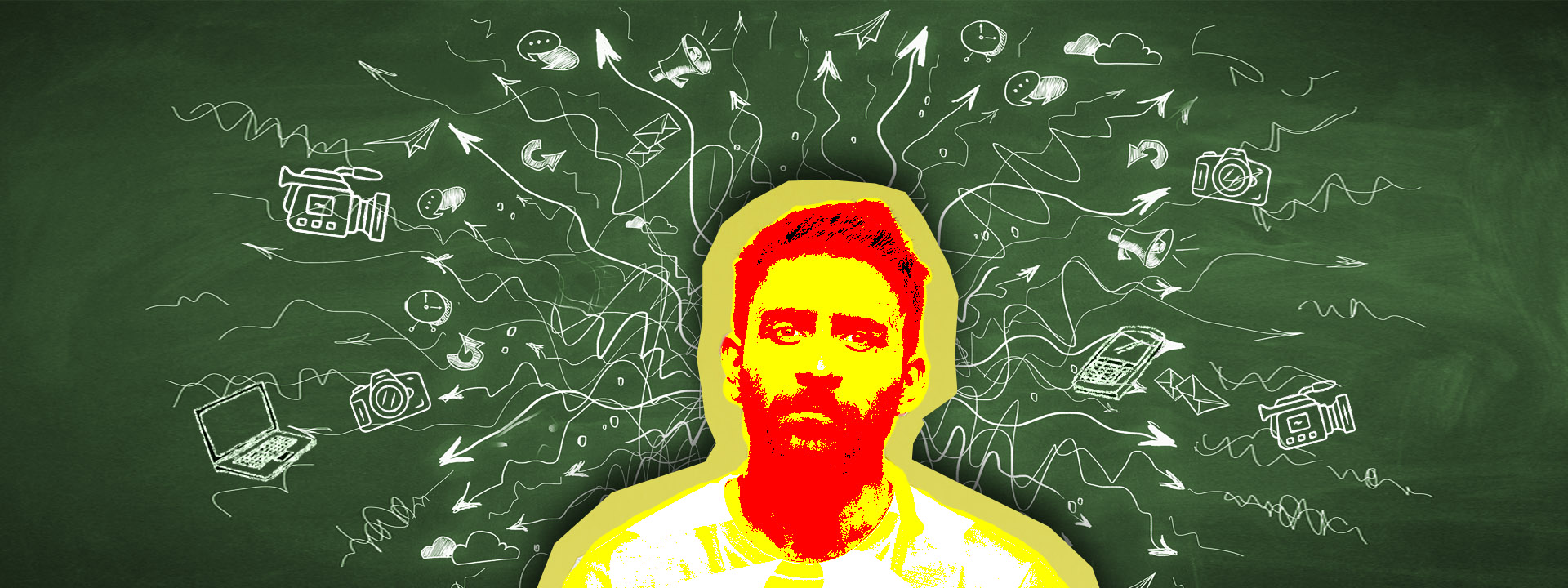

Sri Lankan journalists Tharindu Jayawardena (left) and Rahul Samantha Hettiarachchi working together in 2016 as they investigate illegal land use and forest clearing in the Southern Hambantota district. Both have faced harassment and threats from the authorities in the recent past. (Photo by Amantha Perera)

Hettiarachchi, however, took the call as a sign of things to come. “The information climate had been getting restrictive since the November 2019 presidential election,” he recalls. “There was an increasing attitude among public officials that access to information, even that within the law, should be denied.”

In fact, when Hettiarachchi submitted a request for details on mining approvals months later, a group of sand miners turned up unannounced on his doorstep. They wanted to know why he was seeking information on their business. Comments Hettiarachchi: “It’s standard operational practices that government officials are sharing RTI information within and outside of government departments.”

That doesn’t bode well for Sri Lanka’s media sector, which is already plagued by infighting and what appears to be a decline in skills among reporters and editors. In truth, many journalists are now so wary of the possible consequences of their reporting that self-censorship is fast becoming the norm.

“We live in times where the modus operandi is, ‘let’s be safer than sorry,’” quips Indunil Usgoda Arachchi, secretary of the Sri Lanka Young Journalists’ Association (SLYJA).

“There is a sense of self-preservation within the media community,” she adds. “Those like Hettiarachchi and (freelance journalist Tharindu) Jayawardena buck that trend, but they are in the minority.”

Multiple threats

That minority could even shrink; the constrictive reporting environment that Hettiarachchi had noted seems to have worsened since he received that police officer’s uninvited call. Other Sri Lankan journalists, especially those from minority communities, now also say that they have been sought by police more and more for details on their reporting.

In one of the more alarming cases, a senior police officer went one step further and threatened a journalist on Facebook. On 1 July, Police Senior Deputy Inspector Deshabandu Tennakoon, who is in charge of the Western Province, alleged on Facebook that Jayawardena was publishing fabricated reports and that the natural course of justice awaited him. Jayawardena, who, like Hettiarachchi reports in the Sinhala language, has been investigating police corruption for years.

A five-member media organization coalition consisting of the prominent media-rights groups in Sri Lanka wrote to Police Inspector General Police Chandana Wickramaratne, seeking an investigation into the allegations and the veiled threats. So far, however, no such investigation has been launched.

Usgoda Arachchi meanwhile says that there has been increasing scrutiny directed at journalists, particularly from the police. She says that security units have stopped short of detentions, but make sure that the message is clear: The media is under watch. According to Usgoda Arachchi, SLYJA is aware of at least one incident in which security officials had somehow gotten hold of the log-in details of one journalist’s social media accounts.

Yet to Lasantha de Silva, secretary of the island’s oldest media-rights group, the Free Media Movement (FMM), the current reporting environment is but the latest stage in the decline of a media community crippled with multiple chronic stressors.

“What we are witnessing is the combination of threats,” he says. “There is obviously the security-related threat, there is financial uncertainty, there is the erosion of skills and lack of professional and organizational support for the media community. All of them have been worsening for years.

He indicates that the problems lie not only outside of the media sector, but also within. De Silva points out that while Sri Lanka’s media environment was deteriorating, the journalism community had done very little to stem the slide by way of building networks and enhancing professional skills. Large media organizations, he says, have historically functioned with the aim of not undermining the political and financial goals of the owners, while media start-ups have been by and large driven by a gossip-centric reporting culture.

“There are agendas, and everyone works according to them,” says de Silva. “It is very hard to create a united front.”

Little money and all talk

Usgoda Arachchi, for her part, says that SLYJA has not had much success in lobbying media companies to help ease the financial strain journalists have faced since the first COVID-19 lockdowns in Sri Lanka in late 2020. Payments have been withheld or delayed forcing journalists to look for alternative means of income, SLYJA members have told her.

Hettiarachchi already knows what it is like to be without a steady salary to rely on. But it’s not like he relishes it. He says that unless he succeeds in working on several stories from a single RTI-led investigation or secures funding for the project, he ends up in the red for thousands of rupees.

“To send one round of 300 RTI requests, I have to spend SLR 28,000 (US$130),” he says. “But one story will make me around SLR 10,000 (US$50).”

Both he and Jayawardena express disenchantment with non-government organizations and activists who spent millions of rupees to promote the RTI Act five years back. Now that the law is under pressure, none of them have stepped forward to act, the two journalists say.

“The talk does not match the walk,” Jayawardena remarks.

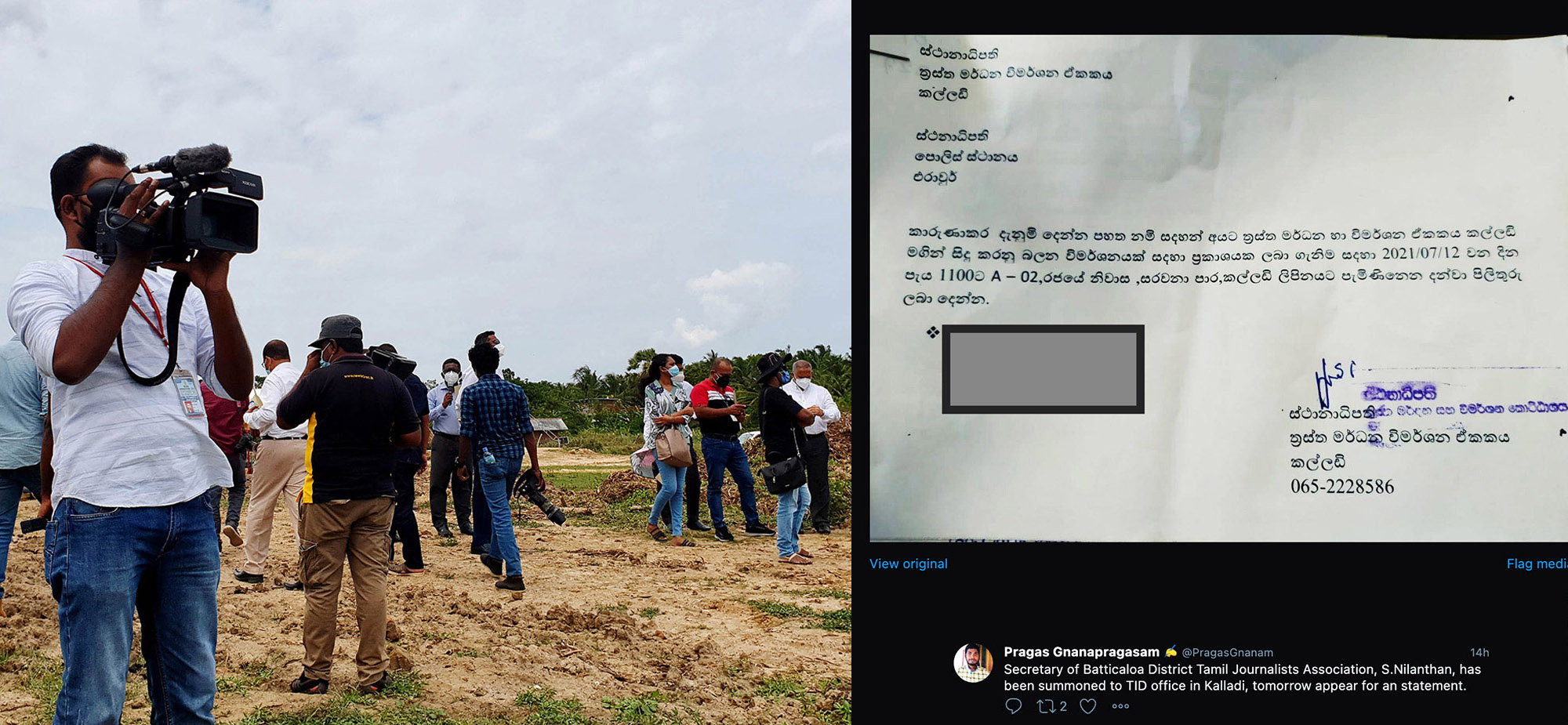

Critics lament that journalism in Sri Lanka is plagued by a host of issues such as infighting and the erosion of skills, all happening under a repressive climate where nearly every reporter’s move is questioned. The photo grabbed from Twitter (right) shows a notice sent in July this year to a Sri Lankan minority Tamil journalist, asking him to report to the Terrorism Investigations Unit of the Kallady Police in Batticaloa in the eastern province of Sri Lanka. (Photo and screen grab by Amantha Perera)

Hettiarachchi fears that with a government that is all about controlling the message, there is a very real threat that the RTI act would be crippled by way of legislation. He notes, “It is the one information channel that is creating information leaks — information that would otherwise not be released.”

There are two vital points to address immediately, if this precarious situation is to be eased, according FMM’s de Silva. The media community needs to address the generational erosion of skills while, at the same time, forming a united front against state supported repression. Neither of these options, however, is plausible in the near future.

“Right now, the media in Sri Lanka is working within a set of assumed boundaries,” de Silva says. “We don’t have the unity as a community nor the skills to address this. If the media community in Sri Lanka, for once, lives up to all their pontifications on freedom and democracy, these few journalists who are taking enormous risks will feel a little safer,”

Asked if he thinks that would ever happen, Hettiarachchi has a two-word reply: “No chance.”●

Amantha Perera is a Sri Lankan researcher at the School of Education and the Arts of the Central Queensland University, Australia. He is currently in the final stages of his master’s research project on the online trauma impact on journalism during the COVID-19 lockdowns.