Editor’s note: On July 2, 2020, nearly a dozen weeks ahead of its scheduled formal departure, US troops quietly pulled out of Bagram Air Base, which had served as the core of their almost two-decade war against the Taliban and al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. Bagram was turned over to the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces, which US officials say should now be capable of keeping the Taliban at bay. Nevertheless, the Pentagon tells Reuters that American armed forces retain “the authority to protect Afghan forces,” should there be a need for it.

On September 11, 2001, Al-Qaeda agents drove commercial airplanes into the Twin Towers in New York City, killing thousands. In retaliation, then-president George W. Bush authorized the use of forces against those responsible for the attacks. In the following years, this authority evolved and expanded into a massive war on terror that the US undertook in the region, sweeping Afghanistan up in the storm. But now, as they wind their Afghan operations down, the US leaves in its wake a lame government incapable of upholding democracy, and extremist camps grown even more rabid.

In the following feature, writer and scholar Ngurang Reena paints a bleak picture of violence and repression, of fear and conflict, that awaits the Afghan people after US withdrawal.

In the longest war fought by the United States, it has been the Afghan people who have paid the highest price. As US and NATO forces prepare to withdraw completely from Afghanistan less than three months from now, Afghans find themselves facing an even grimmer future after nearly four decades of almost continuous conflict.

The US and NATO forces are leaving Afghanistan after almost 20 years of extending it military and civilian assistance. The withdrawal is part of the conditions in the Doha accord signed by the United States and the Taliban on February 29, 2020. The Doha agreement was the second treaty signed as part of the Afghan peace process, with the first being the 2016 pact signed between the Afghan government and the Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin, a political and paramilitary organization in Afghanistan. The international community has been trying to get the Taliban to the negotiating table for yet another round of talks, but the latter have shown little interest. In fact, the Taliban have been acting as if it is a victor in a war – which has left Afghans worried and in fear of what can happen next.

In the years of US intervention, Afghanistan had undergone unprecedented changes. The country has experienced and achieved relative stability and freedom with a democratic form of government. This has been possible largely because of a conscientious and vibrant civil society: groups and individuals championing human rights, women’s participation, and other causes that had been left by the wayside in the years of conflict. Now, however, members of that same civil society have become targets of violent attacks, and they expect worse once the US and NATO troops are all gone.

“The fear is real,” says Shaharzhad Akbar, chairperson of the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission, which celebrated its 19th anniversary this year. “Many have been forced to flee, particularly female journalists. With a shrinking civic space, how can we achieve a peace deal?”

In fact, according to a March 2021 report by the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), over 300 female Afghan journalists have already quit their posts in recent months because of security concerns. Nusrat (not her real name), a journalist working for an international media outfit in Kabul, says that she fears for her life every day while reporting out on field.

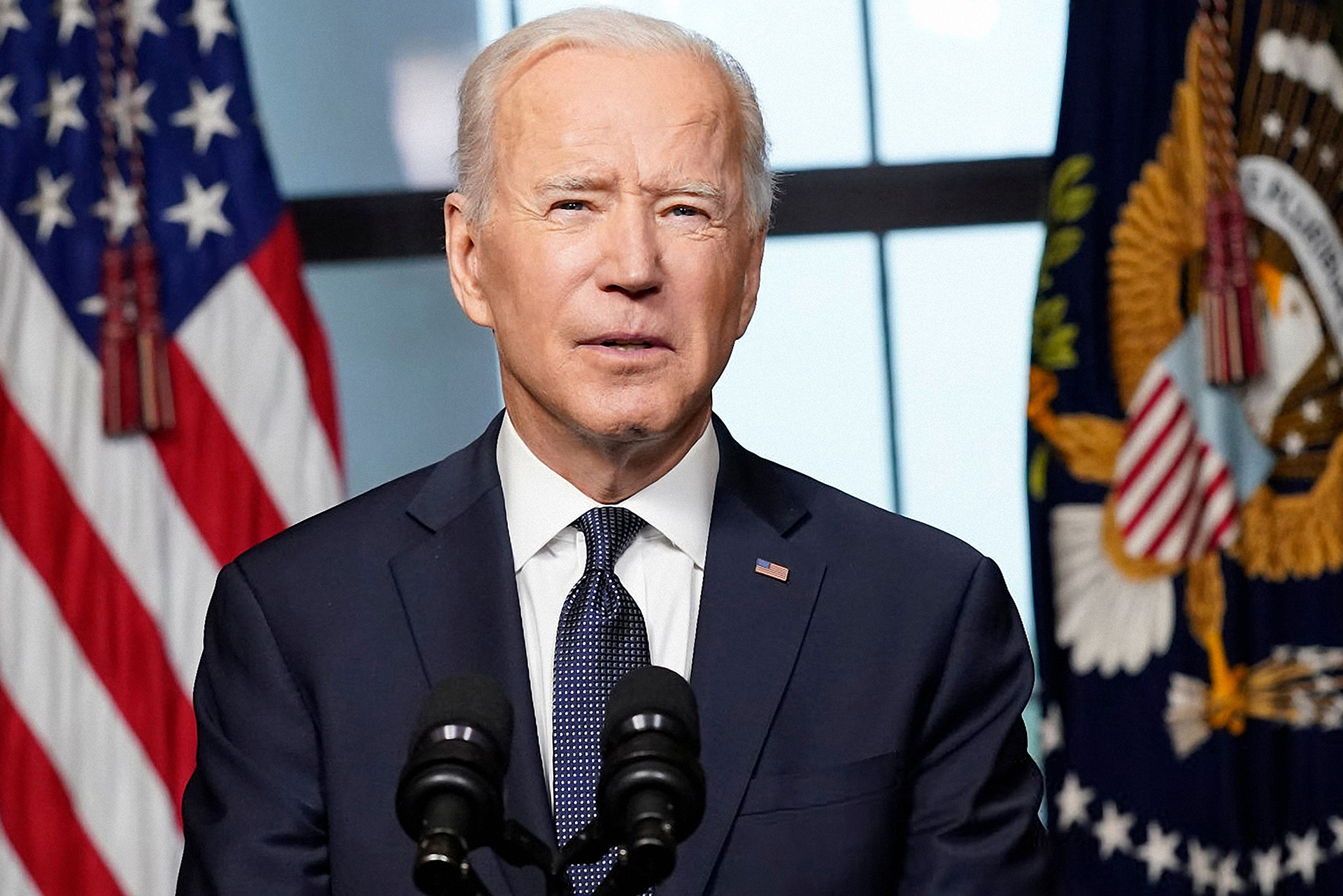

Shortly after he was sworn into office, US president Joe Biden declared that he would pull out troops from Afghanistan by September 2021, ending nearly two decades of war. But the situation on the ground remains far from stable, and civil society groups are afraid that US withdrawal would only make things worse.

“There is no accountability from the Afghan government or the international community for us here,” she says. “My colleagues and I have been advised by our foreign offices to change our routes daily while commuting to the office. I am suffering from an extreme level of PTSD and I can’t function normally.”

Nusrat’s fears are not baseless. In December last year, Enikass radio journalist Malalai Maiwand was assassinated along with her driver. Three months later, three young female media workers, also from Enikass, were killed in two separate incidents. An Afghan affiliate of the Islamic State claimed responsibility for the March killings, saying that the women – all in their early 20s – were slain because they worked for “media stations loyal to the apostate Afghan government.”

There is a strong possibility that the Islamic State and the Taliban will clash in a post-US Afghanistan, even though both share a narrow interpretation of Islam, especially with regards to women. Female reporters, for instance, are seen as defying perceived social and gender norms as defined by the Taliban’s version of an “Islamic Emirate.” Ghizaal Haress, ombudsman of the Afghan government, also says that the Taliban have secretly prepared their own constitution that omits any mention of women.

So far, the Taliban are attracting more attention than Islamic State. The Taliban already have 50 districts under their control, with a UN envoy commenting recently that their strategy seems to be to position themselves in places from which they can seize provincial capitals more easily. And as they continue to confront and challenge government forces across the country, the Taliban have also been busy targeting “dissenters” such as journalists, activists, and even religious leaders and academics. Even frontline medical workers have not been spared, with doctors and nurses killed in the midst of the pandemic.

According to the 2019 UN Secretary General Report on Children and Armed Conflict, schools and hospitals remain among the most attacked by terrorists in Afghanistan, along with bridges, roads, and other infrastructures in the country. For sure, such attacks have not been without fatalities. Just last May, some 85 people, among them schoolgirls, were killed in an attack outside the Sayed ul-Shuhada High School in Kabul.

In a recently released documentary by Vice News, a Taliban representative promises a better Afghanistan under a Taliban regime. The question, of course, is better for whom? In the documentary, the Taliban representative sounds determined to restore the “Islamic Emirate,” which was destroyed by the Western intervention, even as he reassures viewers of “accommodating” the rights of all, including those of women.

As the date of the US troops’ withdrawal draws near, Taliban forces have upped their activities, bringing some 50 districts under their control. The rebel group promises to usher in a better age for Afghanistan after America’s exit, but, if their shoddy track record with women’s rights is any indication, gender equality seems to be far down the Taliban’s list of priorities.

Dr. Omar Sadr of the American University in Afghanistan says that the country’s endless war is also “a war of perceptions and representations, with all the parties to the conflict trying to control public perceptions – including Taliban.” The reality is much more muddled and distressing. For example, while Washington has tried to spin the deal it struck with the Taliban in Doha as a peace pact and has claimed success, the accord has brought no peace. Instead, it has only “legitimized” the Taliban as a party worthy of bringing to the negotiating table. Afghans themselves have asked why, when majority of them have continued to reject the Taliban, is the group representing them in negotiations concerning their future.

Comments Sadr: “The current trajectory of the peace process has done more harm and alienated the people of Afghanistan – the ultra-centralized and elite-driven approach has excluded groups peripheral to the system and created a bipolar peace process between the elites and the Taliban.”

Indeed, not a few have noted that in the 21-member government delegation in the intra-Afghan peace negotiations, only four were women; the Taliban team members were all male.

As the spate of violence continues, Afghans’ optimism and hope for peace have significantly decreased. According to the Institute of War and Peace Studies in Kabul, only 57 percent of the respondents in a survey conducted from September to October 18, 2020 expressed optimism for the country’s prospects for peace. In a survey conducted during summer 2020, the corresponding figure was 86 percent.

As the spate of violence continues, Afghans’ optimism and hope for peace have significantly decreased. According to the Institute of War and Peace Studies in Kabul, only 57 percent of the respondents in a survey conducted from September to October 18, 2020 expressed optimism for the country’s prospects for peace. In a survey conducted during summer 2020, the corresponding figure was 86 percent.

Many Afghans have called out the Afghan government for failing to protect civilians. But the reality is that it may be hard-pressed to do that, relying for years on outside help to keep law and order in a strife-prone country. One government worker who asked to remain anonymous says that he risks his life every day that he remains a civil servant. Recently, he says, an improvised explosive device was planted near his home. Insists the government worker: “We are doing our best to provide security and protection to civilians, often at the cost of our own lives.”

He also says, “Taliban is coming for everyone if the US won’t keep its promise of withdrawal.”

Following the withdrawal of its troops from Afghanistan, the United States plans to continue to provide financial assistance to Afghans and to build on existing “over-the-horizon” anti-terrorism capacity in the region. But it remains to be seen if such development and humanitarian aid – from the United States and other members of the international community – can make a difference in a country where a brutal and vicious group is bent on stifling the voices of those who do not share its views. It has also been argued that outsiders professing their desire to help bring peace to Afghanistan have made little effort to first understand the country’s political and social systems, which are marked by cultural and moral diversity.

Afghanistan is a resilient country, and its civil society is ready to resist extremism and to fight for freedom. But the country’s chance at achieving lasting peace lies not only in the hands of the Afghan peoples. The continued engagement of the international community with Afghanistan – long after the US and NATO forces leave its shores – is crucial if Afghans are to get the political settlement and sustainable peace they desire and deserve. ●

Ngurang Reena is a Ph.D. candidate at Center for European Studies, School of International Studies, of the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.