Hong Kong has been traditionally seen as a media hub for the Asia-Pacific region, particularly where English-language coverage is concerned. That no longer seems to be the case, and recent events may even accelerate the departure of media outlets from Hong Kong.

Last week saw the sudden shutdown of Apple Daily, Hong Kong’s major pro-democracy newspaper, after 26 years of operation. The newspaper printed one million copies – roughly enough for one in seven Hongkongers – for its last edition. That prompted long lines to form in front of newsstands and a crowd braved the rain outside of the newspaper’s offices just to get copies. At midnight last Thursday, the newspaper’s website and social media accounts also went dark, with netizens rushing to back up articles before the site shutdown.

The week before its closure, Apple Daily was raided by 500 police officers, with 38 computers seized from the newspaper’s offices and five media executives arrested, among them its chief editor, chief executive officer, and chief operations officer. Last August, about 200 police officers had also raided the paper’s headquarters. What ultimately brought down Apple Daily, however, were not the raids, but the freezing of bank accounts belonging to companies linked to it; Apple Daily itself had HK$18 million dollars (US$2.318 million)of its funds become suddenly inaccessible. Accounts belonging to Apple Daily owner Jimmy Lai had already been frozen in May.

Reports suggested that Apple Daily had originally intended to print its final issue on Saturday, 26 June, following a board meeting scheduled on Friday, 25 June. But then the newspaper decided that its 24 June issue would be its last, indicating that the noose was tightening faster than expected.

Apple Daily’s sorry fate is the culmination of years of deteriorating press freedom in Hong Kong. Its fast and forced closure also bodes ill for press freedom in what is supposed to be one of China’s Special Administrative Regions or SARs.

The forced shutdown of popular pro-democracy newspaper Apple Daily in Hong Kong sounded the death knell for press freedom in the beleaguered city.

Dark days ahead for Hong Kong media?

The emerging picture, in fact, is that the sustained crackdown on news outlets in Hong Kong is being made with the aim of turning the media environment in Hong Kong into a mirror image of its counterpart in mainland China. In this respect, what was previously thought of as unimaginable in Hong Kong may soon be a common, everyday experience there. An early example may be the adoption of a firewall in Hong Kong to prevent citizens from accessing content that authorities find objectionable, similar to the “Great Firewall” that exists in China.

There are already some indications that restrictions on internet access may imminently take place in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong Charter, a statement written by Hong Kong activists living in exile, became inaccessible in Hong Kong, due to pressure on hosting service Wix.com, which later reversed its move. Internet restrictions may push Hongkongers to rely on VPNs in order to access news reports from international media outlets, with access to information on the outside world becoming more difficult in Hong Kong. It is not farfetched as well that Hong Kong residents would one day end up relying on news outlets based overseas for accurate information on what is happening in their own city.

There are already some indications that restrictions on internet access may imminently take place in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong Charter, a statement written by Hong Kong activists living in exile, became inaccessible in Hong Kong, due to pressure on hosting service Wix.com, which later reversed its move. Internet restrictions may push Hongkongers to rely on VPNs in order to access news reports from international media outlets, with access to information on the outside world becoming more difficult in Hong Kong. It is not farfetched as well that Hong Kong residents would one day end up relying on news outlets based overseas for accurate information on what is happening in their own city.

It remains to be seen if Hong Kong authorities will next resort to enacting sweeping legal charges against journalists, similar to what takes place in China on a regular basis. But Apple Daily’s saga has revealed some of the tactics that the Hong Kong government may use in the future against media outlets operating in Hong Kong. For one, large-scale police raids staged with the aim of publicly intimidating the media sector may become increasingly common. For another, the freezing of bank accounts as a means of shutting down media organizations leaves smaller outlets more vulnerable to such threats.

Moreover, the specific charge slapped on Apple Daily executives looks like a new version of what protesters in Hong Kong had found themselves accused of: collusion with foreign powers to try and undermine Hong Kong society. In the case of the Apple Daily executives, they were accused of publishing articles with the hopes of inciting foreign powers to enact sanctions against Hong Kong.

The charge about sanctions suggests that legislation passed by members of the international community regarding Hong Kong may now be used as a means of targeting Hong Kong journalists. Countries such as the United States, for instance, have imposed sanctions on Hong Kong through legislation such as the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, with the claim that this is a means of reacting against the worsening political freedoms in the Chinese SAR.

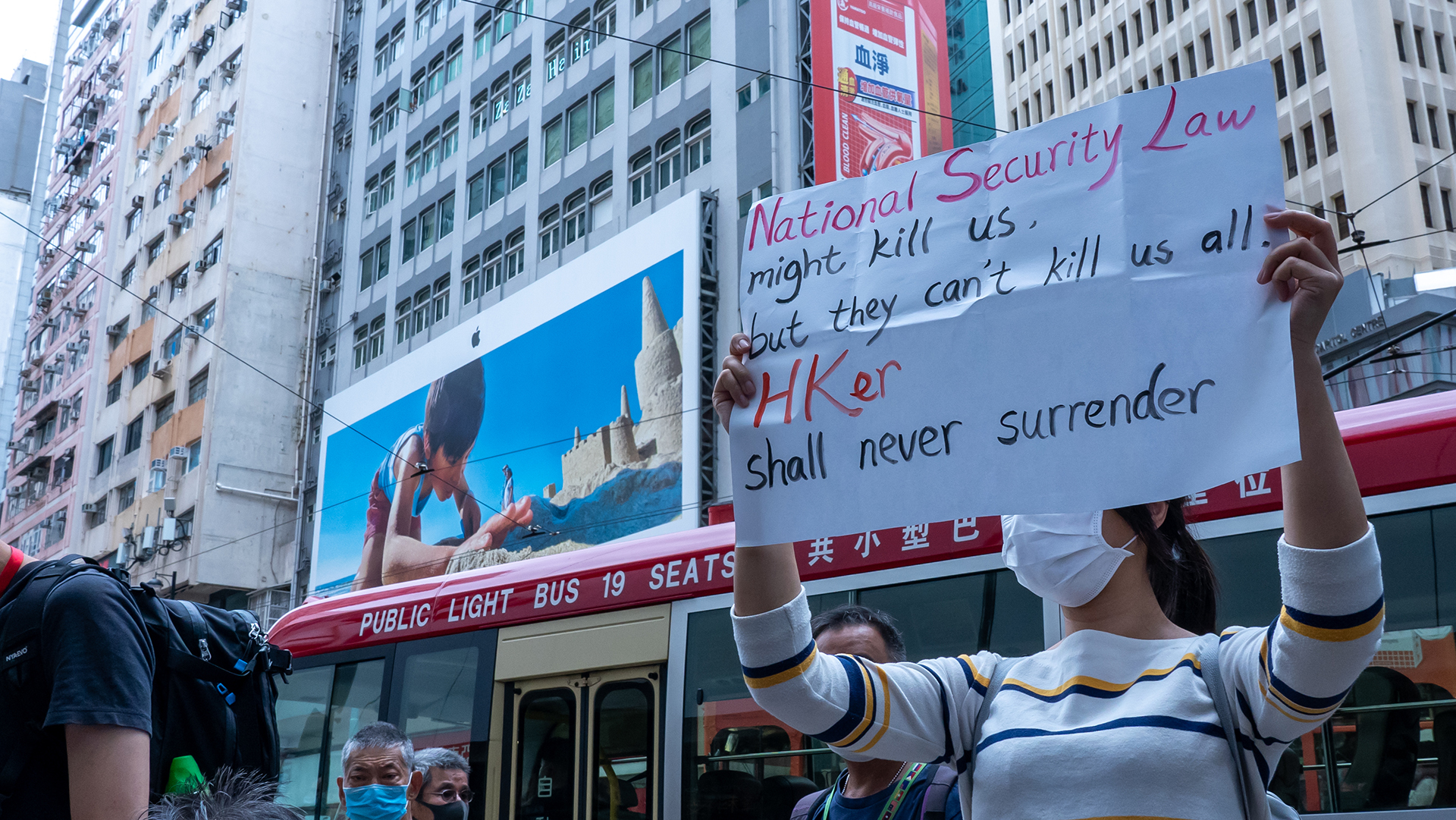

Thousands of demonstrators convened in Causeway Bay to protest against the looming national security law announced by Beijing in late May 2020.

More media outlets likely targets

For sure, Apple Daily is just one of the media organizations that have been targeted under the auspices of the national security law passed last June by China’s National People’s Congress, in a manner that circumvented the Hong Kong Legislative Council. (Hong Kong officials are still probing the limits of their authority under the national security law. The first trial conducted under the national security law took place the same day as Apple Daily’s announcement of its shutdown.)

Another media outlet that has come under scrutiny from Hong Kong authorities in the past several years has been public broadcaster RTHK, which has generally been highly critical of the actions of the Hong Kong government. Yet after pressure from the Hong Kong government, the contracts of prominent RTHK journalists were not renewed, fines and jail sentences were imposed upon RTHK journalists for routine reporting as a means of punishment, and RTHK programs more than a year old were deleted. Less than a week after the Apple Daily shutdown, two RTHK programs were axed abruptly, with their hosts informed of the move only on the day of the final broadcast.

One of the remaining major online pro-democracy media outlets may also be on the sights of Hong Kong authorities. In apparent preparation for any unwelcome move from the government, Stand News has announced that it would be deleting all op-ed articles published before May and will no longer accept donations.

One reason for this could be that if there is any record of the online newspaper’s past articles, they may be used later against the writers or the outlet’s officers. Again, Stand News may be learning from Apple Daily’s experience. When the national security law was passed last year, the Chinese and Hong Kong governments had stated that the law would not be retroactive. Yet this does not seem to be the case, with Apple Daily’s Jimmy Lai prosecuted on charges connected to participating in political gatherings that took place in 2019.

Indeed, it seems Hong Kong authorities are not yet done with Apple Daily journalists, even though the newspaper has ceased operations. Just recently, former Apple Daily managing editor Fung Wai-kong was arrested at Hong Kong International Airport as he was on his way to the United Kingdom, suggesting that former Apple Daily staff members who try to leave Hong Kong may also be prevented from doing so.

In the meantime, Apple Daily’s closure has been watched by keen eyes in Taiwan, which similarly faces threats to its democracy from China. Beijing has also sought to make unification more attractive for Taiwan with the promise of allowing for a separate system of government under the auspices of “One Country, Two Systems,” which it had supposedly applied in Hong Kong until 2047. But according to Lev Nachman, a postdoctoral researcher at the Fairbanks Center at Harvard University, the shuttering of Apple Daily is likely to push Taiwan further away from China.

As Nachman put it, “The spectacle of the Apple Daily closing in Hong Kong will only reinforce Taiwanese civil society’s disdain for any sort of One Country, Two Systems agenda the PRC pushes forward.” ●

Brian Chee-Shing Hioe is one of the founding editors of the Taiwan-based New Bloom Magazine.