When Gita*, a woman in Kolkata, contracted the coronavirus, she was admitted to a hospital that had run out of remdesivir. Gita’s family was forced to buy the medicine themselves from the black market, where they coughed up between 15,000 to 60,000 rupees (US$205 to US$822) per 100-milligram vial of remdesivir.

The original price for a vial of the drug is anywhere between 1,000 and 5,400 rupees (US$13 and US$73). Political analyst Saurav Dutt, Gita’s cousin, says that on the black market, the prices of medicines such as remdesivir and tocilizumab and oxygen cylinders range from five to ten times their regulated retail prices.

The family shelled out about 200,000 rupees (US$2,736) for the vital supplies needed by Gita during her five-day hospital stay. However, this was still not enough. “My cousin passed away at the age of 50,” says Dutt.

Amid India’s apocalyptic COVID-19 surge, acute shortages of life-saving medicine and oxygen drive desperate Indians to buy the life-saving goods from the clandestine market. The booming black market highlights the weakness of the country’s healthcare system and the inequities between the haves and the have-nots.

The shortage of hospital beds led to a long wait for this sick woman outside the premises of Lok Nayak hospital in New Delhi. (Photo: Bhat Burhan)

A healthcare meltdown

As India was hit with a deadly second wave of COVID-19 that started in April, the rapid rise in cases put huge pressure on its healthcare system. Soon, hospital beds, oxygen, ambulances, drugs, and healthcare workers were all in short supply.

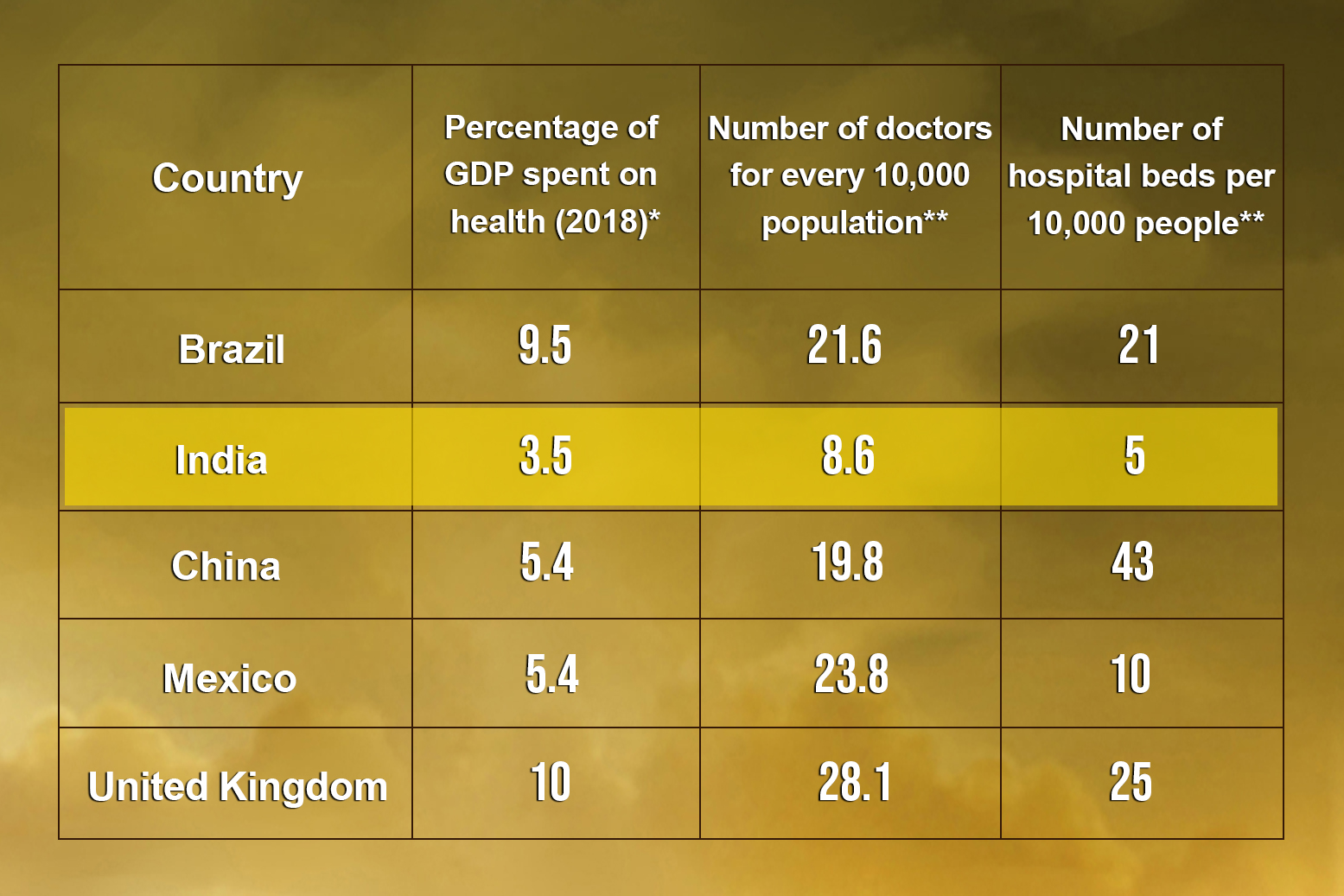

India’s healthcare system was weak, to begin with. Among countries with a similar level of income and economic growth, India spends very little on health. “Despite being the sixth-largest economy in the world, India spent a paltry 3.5% of its GDP (in 2018) on health,” writes Sumit Mazumdar in The Conversation. “By comparison, Brazil spent 9.5% of its GDP on health, China and Mexico 5.4%, and the UK 10%.”

As a result, among the countries above, India has the fewest doctors — 8.6 doctors — per 10,000 people, according to the Human Development Report 2020. India also has the fewest hospital beds — 5 beds — per 10,000 people.

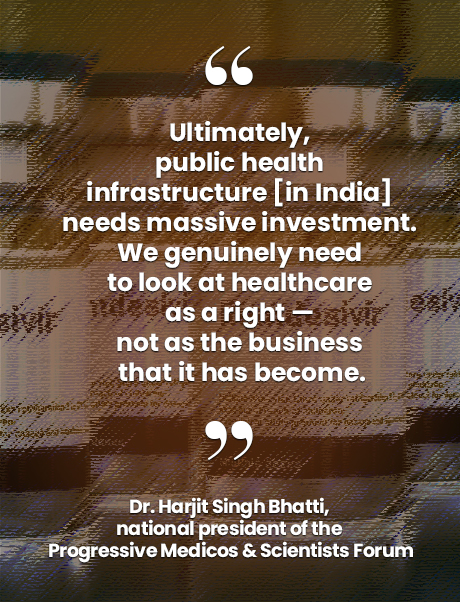

Dr. Harjit Singh Bhatti, national president of the Progressive Medicos & Scientists Forum, works in a private hospital in New Delhi. Bhatti has seen the hospital turn away “everyone, from influential army personnel to medical professors.” He says, “There were no beds and no oxygen.”

The shortages, worsened by the fact that time is of the essence in treating COVID-19 cases, resulted in a vacuum that was increasingly filled by a booming black market. Even hospital beds are being sold on the clandestine market, along with slots for quicker burials at overburdened crematoria.

As scammers sell fire extinguishers disguised as oxygen cylinders and saline in remdesivir vials, surging COVID-19 deaths has become a grim reality. (Photo: Bhat Burhan)

The poor’s burden

Bhatti has observed how the black market has made lives easy for the privileged. “I’ve watched patients here who have been somehow able to procure medicines which are just not available in our known networks,” he says. “It’s clear that they’re buying these medicines in the black market.”

Bhatti fears that for India’s poor, the ability to pay exorbitant prices for vital supplies and, consequently, the chances of surviving COVID-19, are slim. He says, “In a country where the public health infrastructure is weak and investment in it by the state remains abysmally low, privatized healthcare is the only real option.” However, the cost of private medical care is beyond the reach of the poor.

According to Mazumdar, “Most of the money spent on health in India comes directly out of people’s own pockets, with government spending on health being one of the lowest in the world, averaging about US$38 per person per year over the past two decades.”

Slots for quicker burials at overburdened crematoria are being sold on the clandestine market. (Photo: Bhat Burhan)

Scam alert

The direct effect of the booming black market is obvious: Those without sufficient funds, or contacts, have no option but to rely on the kindness of strangers or fate. Sadly, scammers have worsened India’s COVID-19 misery. They have ripped off desperate patients and relatives by selling fake medicines, fire extinguishers that are disguised as oxygen cylinders, and recycled personal protective equipment, reports Al Jazeera. There have also been reports of people being saline in remdesivir vials.

Nidhi Suresh, a journalist, and her friend were duped when they were searching for oxygen cylinders for the friend’s uncle who had COVID-19. They found a supplier named Sachin Agarwal and paid him 25,400 rupees (US$346) after he insisted that they buy two cylinders. The cylinders were never delivered.

After Suresh tweeted about their ordeal, she found out that Agarwal scammed at least a dozen people for over 450,000 rupees (US$6,141). The journalist filed a complaint with the authorities.

Ways forward

The efforts of individuals like Suresh are not enough to stop scammers. The government needs to take steps to curb scamming and the black market.

Dr. Chandrakant Lahariya is a public health policy expert and epidemiologist. He emphasizes the need for the central government, through agencies like the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, to control the supply and production of medication that is in short supply. He says, “Furthermore, the enforcement mechanisms to take these steps need to be tightened.”

In May, an editorial in the Hindustan Times, called for sustained efforts to curb the black market sale of beds and essential medical supplies and the sale of fake medicines and medical devices. It stated that such efforts require “all agencies enforcing different applicable laws such as the Indian Penal Code, the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, the Essential Commodities Act, the Prevention of Black Marketing and Maintenance of Supplies of Essential Commodities Act, the Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodities) Rules, the Epidemic Act and the Disaster Management Act, to come together and set up an exclusive cell to deal with all COVID-related unfair practices. Besides their own investigations, these cells in each state should follow up on consumer complaints of overpricing and fake drugs provided through toll-free telephone and WhatsApp numbers.”

In May, an editorial in the Hindustan Times, called for sustained efforts to curb the black market sale of beds and essential medical supplies and the sale of fake medicines and medical devices. It stated that such efforts require “all agencies enforcing different applicable laws such as the Indian Penal Code, the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, the Essential Commodities Act, the Prevention of Black Marketing and Maintenance of Supplies of Essential Commodities Act, the Legal Metrology (Packaged Commodities) Rules, the Epidemic Act and the Disaster Management Act, to come together and set up an exclusive cell to deal with all COVID-related unfair practices. Besides their own investigations, these cells in each state should follow up on consumer complaints of overpricing and fake drugs provided through toll-free telephone and WhatsApp numbers.”

In April, the Bombay High Court said that “in order to deter unscrupulous persons from indulging in black marketing of life-saving drugs like Remdesivir, police, and courts should ensure that probe and trial in such cases are completed swiftly,” reports The New Indian Express.

Police officials across the country have been busting rackets and conducting raids. Some are sharing advisories on how to protect oneself from scams.

However, the underlying cause of India’s weak healthcare system needs to be addressed. Bhatti says, “Ultimately, public health infrastructure needs massive investment.” He concludes, “The private sector exists, but it is neither inclusive nor does it serve the needs of the moment. We genuinely need to look at healthcare as a right — not as the business that it has become.” ●

Mehk Chakraborty is a freelance multimedia journalist and researcher who covers social movements, human rights, LGBTQ+ culture, travel, and the arts. She has an MA in Political Analysis, and her work has appeared on BBC, The Daily Beast, Roads & Kingdoms, Waging Nonviolence, The Blueprint, and several other international publications.

Public health care in India needs a shot in the arm

By Asia Democracy Chronicles

Among countries with a similar level of income and economic growth, India spends very little on health. As a result, the country has the fewest doctors and the fewest hospital beds per 10,000 people.

* Data from The Conversation

** Data from Human Development Report 2020