Stone the rapists to death, castrate them, and hang them in public. Many Pakistanis demanded their pound of flesh after two men raped and robbed a woman — whose name has not been publicly released — in front of her two children in September 2020. The shocking crime took place on the Lahore-Sialkot motorway in Punjab.

The rape triggered public outrage and nationwide protests.

In December 2020, Pakistan’s president approved a tough new anti-rape law that includes the establishment of special courts for rape trials and the chemical castration of serial rapists. Human rights groups denounced the new legislation as regressive.

On March 20, a special court in Lahore convicted the two men of gang rape, kidnapping, robbery, and terrorism offenses. They were sentenced to death.

The case offers the faintest flicker of hope in a country that has an abysmal rape conviction rate, with official data putting it as low as 0.3% from 2015 to 2020. Out of the 22,037 rape cases reported during that period, only 77 offenders have been convicted.

In addition, Pakistan’s staunchly patriarchal culture allows victim blaming, the so-called “virginity tests” in rape examinations, and revenge rape. As a result, the wheels of justice turn too slowly for the victims. In several cases, the victims are forced into marrying their perpetrators or even committing suicide while criminals roam around freely.

Activists have been fighting for Pakistani women’s rights for years. They still face a long battle ahead.

A rape “every 20 minutes”

In Pakistan, a woman is raped every two hours, according to a Human Rights Commission of Pakistan report. However, Haseeb Khawaja, chief coordinator of the Pakistani Men Against Rape campaign, believes that it is more accurate to say that “a woman is raped [nearly] every 20 minutes.” He says that “only 10% of rapes are reported because in most cases women do not report to the police, or their families do not allow them to register cases.”

Recent figures of violence against women in Pakistan during the pandemic remain high. In 25 districts, there were 2,297 cases of violence against women in 2020. This is an alarming increase from the 2,650 cases of violence against women reported in the country between January 2012 and September 2015, according to the Ministry of Human Rights.

Victim blaming is one reason the rape victims hesitate to come forward. After the September 2020 rape, the Lahore Police chief made a public statement suggesting that the woman was herself at fault because she should not have been traveling “without her husband’s permission” on a motorway late at night. His statement led to nationwide protests demanding police reform.

Prime Minister Imran Khan has been criticized for victim blaming. Local human rights groups have accused him of being a “rape apologist” after he blamed a rise in sexual assault cases on how women dress, reports the BBC. In April, during a two-hour-long, question-and-answer interview with the public on live television, Khan said women in Pakistan should remove “temptation” because “not everyone has willpower.”

Former president Pervez Musharraf also cast suspicion on rape victims. In 2005, he was slammed for saying in an interview with The Washington Post that “rape has become a moneymaking concern, with some Pakistanis believing it was a ticket to settling abroad,” reports Al Jazeera. During the interview, Musharraf said that he had arranged for a visa and for US$50,000 to be given to a Pakistani medical doctor who was raped by a masked intruder so she could leave the country. The doctor has applied for asylum in Canada.

A “second trauma”

The “virginity test” has long been a routine part of criminal proceedings in Pakistan, notes Human Rights Watch. It is a long-standing practice in the Islamic country that is used to assess a woman’s so-called honor.

The test involves a medical examiner inserting two fingers into a woman’s vagina to determine her virginity. According to the World Health Organization, the procedure holds no scientific merit.

The test is based on the unscientific and misogynist assumption that a woman “habituated to sexual intercourse” is less likely to have been raped. Police and prosecutors in Pakistan have used these tests to accuse rape victims of illegal sexual intercourse and treat them as criminals. Rape victims describe the test as a “second trauma” after the sexual assault, which leaves psychological scars, reports Deutsche Welle.

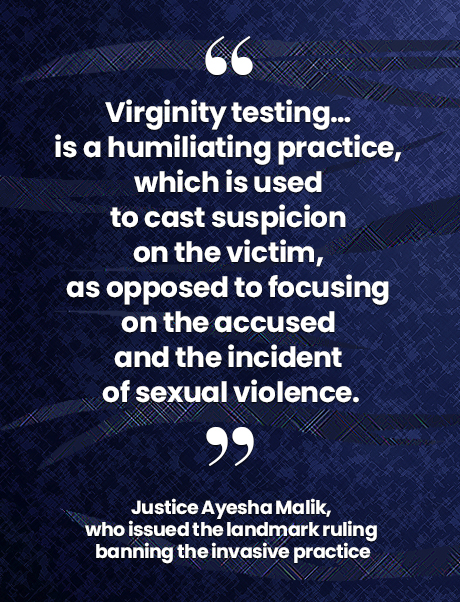

In January, a Pakistani court outlawed the invasive practice in an unprecedented ruling. In making the judgment, Justice Ayesha Malik is reported by The Guardian as saying that: “Virginity testing [has] no scientific or medical requirement, yet [is] carried out in the name of medical protocols in sexual violence cases. It is a humiliating practice, which is used to cast suspicion on the victim, as opposed to focusing on the accused and the incident of sexual violence.”

The BBC reports that “the ruling applies in Punjab but may serve as a precedent for petitions in other provincial high courts.” Currently, the test is conducted in the three other provinces of Pakistan.

A barbaric practice

The prevalence of revenge rape in rural Pakistan is another barbaric reality, where innocent women become the victims of crimes committed by their male family members. In this heinous practice of punitive rape, village councils often order revenge rape, a sexual assault of a woman for the crime committed by her brother.

These councils have no legitimate standing, but they wield great influence. The 2002 revenge gang rape of Mukhtar Mai on the order of the village council gained global attention and showed the brutish face of Pakistani society.

Prime Minister Imran Khan was dubbed a “rape apologist” after he blamed a rise in sexual assault cases on how women dress.

Snail-paced justice

On average, legal experts believe that the average rape trial in Pakistan lasts from three to five years. In the case of Mai, she has not found justice for almost two decades since she was gang-raped.

Her case has taken many twists and turns. In 2002, an anti-terrorism court sentenced six out of the 14 accused people to death: four on rape charges, while two others were sentenced as members of the village council. Eight of the accused were released.

However, in 2005, the Lahore High Court acquitted five of the six convicts, and one convicted man’s death penalty was converted to life imprisonment.

Mai challenged the verdict in the Supreme Court, but the judges rejected her appeal in 2011. She filed a review petition before the same judges to formulate a larger bench to hear the case stating that she is not satisfied with the court’s acquittal decision. The Supreme Court conducted several hearings, the latest one in March 2019, and Mai’s review petition was dismissed.

Mai challenged the verdict in the Supreme Court, but the judges rejected her appeal in 2011. She filed a review petition before the same judges to formulate a larger bench to hear the case stating that she is not satisfied with the court’s acquittal decision. The Supreme Court conducted several hearings, the latest one in March 2019, and Mai’s review petition was dismissed.

In a country where rape victims face an uphill battle for justice, it is believed that the police and the country’s leaders need to be trained in gender sensitization so that they can put an end to victim blaming and encourage victims to report that they have been raped. The state must undertake legal reforms to shorten the trial time of rape cases, improve the conviction rate, and put an end to “virginity testing” and punitive rape.

According to legal experts, the average rape trial in Pakistan lasts between three and five years.

Against this grim backdrop, several women’s rights groups, such as War Against Rape, have been fighting for the rights of rape victims. The NGO has been working for the past 32 years and has 456,530 people who have been coming forward to strive and change Pakistani attitudes toward the victims.

Still and all, justice remains elusive for many rape victims such as Mukhtar Mai — a reality that only serves to reinforce Pakistan’s misogynistic culture of treating women as objects of male sexual desire and blaming rape victims. ●

Haroon Janjua is an award-winning journalist covering South Asia based in Islamabad, Pakistan. He received the 2015 United Nations Correspondents Association Award, the 2015 IE Business School Prize for best journalistic work on Asian Economy, and the 2015 Global Media Award from the Population Institute in Washington DC.