For many years, Vietnam has built its temples using wood from Laos and Cambodia. But now that their neighbors’ forests have grown nude, Vietnamese firms have set their sights on a new treasure trove of timber: West-Central Africa.

The Congo Basin spanning six countries including Cameroon is the world’s second-largest tropical rainforest system, covering more than 2 million square kilometers of land. It represents over 90 percent of the continent’s rainforests and is home to a divine diversity of species, many of which are found nowhere else on the planet.

Cameroon, a small nation lying at the strategic junction between Western and Central Africa, forms the Basin’s northwestern tip. Though more than 10,000 kilometers apart, Cameroon’s combination of rich soil and lax laws have made it the perfect playground for Vietnam’s shadowy businessmen.

According to a new report by the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), an international non-profit organization that seeks to protect the global environment, various Vietnamese companies are damaging Cameroon’s forests and its economy through logging.

The independent report, “Tainted Timber, Tarnished Temples: How the Cameroon-Vietnam Timber Trade Hurts the Cameroonian People and Forests,” was conducted over three years and employed undercover investigators, who accrued several damning first-person accounts from key players in both countries.

The EIA report found that these companies were extracting timber to export back to Vietnam in violation of export laws, and were engaging in labor exploitation and discrimination, tax evasion, and illegal logging, among other dubious practices.

Using timber largely as architectural materials for Buddhist temples and private houses in Vietnam, Vietnam has emerged as the second-largest timber processing hub in Asia, after China.

The Vietnamese socialist government has consistently condemned the imperialism and economic exploitation that has resulted from capitalism. In a recent article about socialism, Nguyen Phu Trong, the Secretary General of the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP), declared that the country should strive for “sustainable development… instead of usurping natural resources and destroying the environment.”

A socialist government is regarded as the alternative to capitalist countries, which have failed to address the problems of environmental damage and labor exploitation. However, this issue shows that companies operating under the authority of a government with such an ideology are perfectly capable of environmental, economic, and labor abuses – especially when it concerns less developed countries.

The private companies named in the report include Dai Loi Trading Co. Ltd., Xuan Hanh Wood Company, Thang Long Import-Export Company Ltd., Hai Duong Wood Import-Export Company Ltd., and an unregistered Vietnamese company represented by someone known as Le Jessan Tan. All of these entities are reportedly private companies, meaning no links with the government have been found.

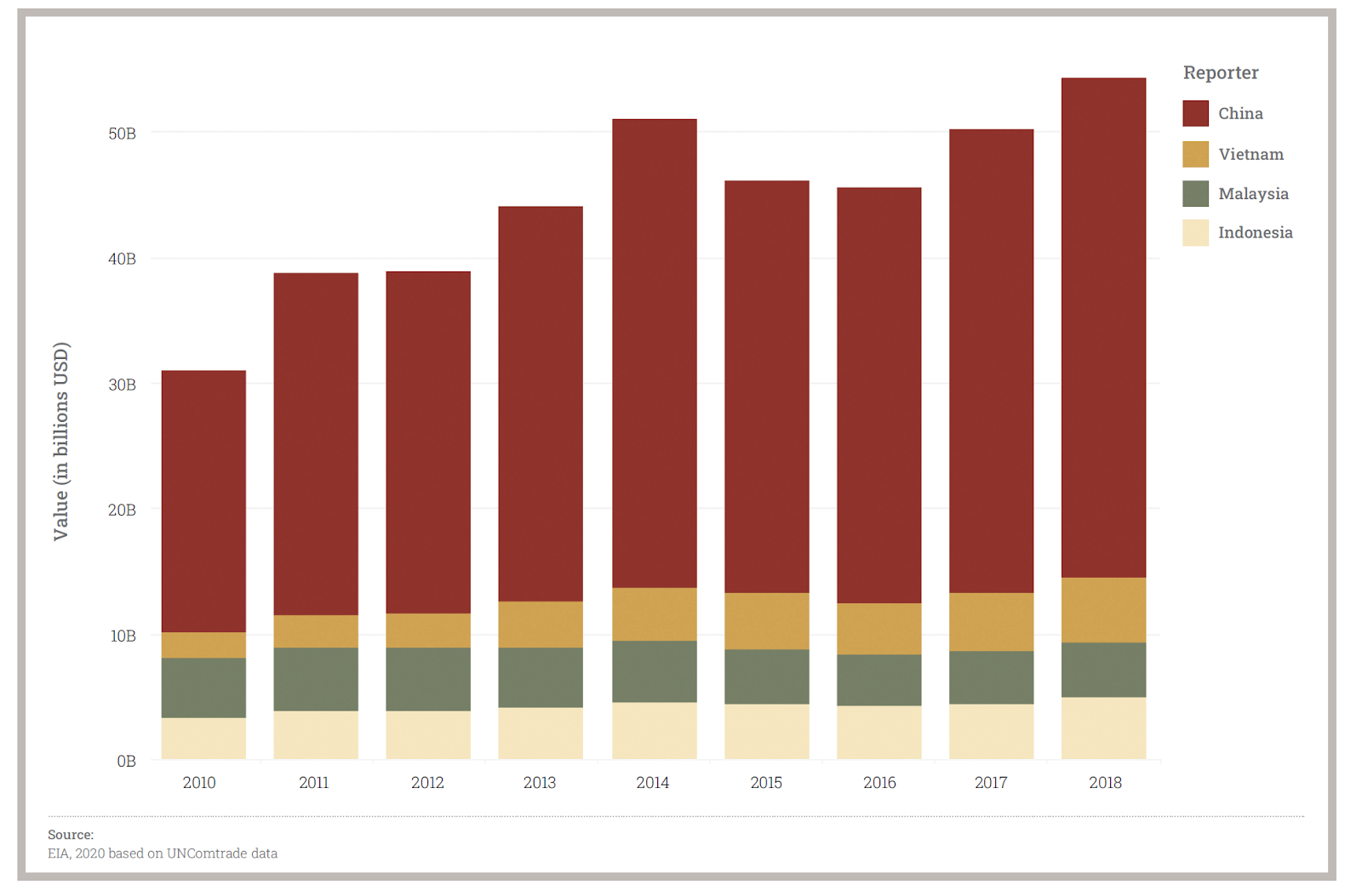

The total value of timber imports and exports from the prominent timber processing countries in Asia. Over the years, Vietnam has grown to be the second-largest importer in the region, behind only China. Graph from EIA.

Environmental and labor abuses in Vietnam

In its ideological doctrine, the VCP consistently claims that the socialist government is “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” Land in Vietnam is also constitutionally “owned by the people,” and the private ownership of land is theoretically unconstitutional. The VCP’s socialism is understood as a way to uplift the common people by limiting the power of private businesses and corporations.

But despite Vietnam’s commitment to socialism, stories about environmental and labor exploitation by its private sector are not new. Rich in natural resources and home to a large population providing cheap labor, the country is ripe for exploitation.

The 2016 Formosa environmental disaster is a case in point. At the time, Hung Nghiep Formosa Ha Tinh, Ltd., a Vietnamese private company, was heavily polluting the seas in central Vietnam, leading to large-scale die-offs in fish and other marine life. The Taiwanese Formosa Plastics Group is a primary investor of Hung Nghiep Formosa Ha Tinh, Ltd.

The disaster also affected human lives. As a result of massive pollution, many people either died or became seriously ill. Some were even believed to have developed cancer from diving in the sea, eating poisonous fish, or being exposed to the company’s chemicals.

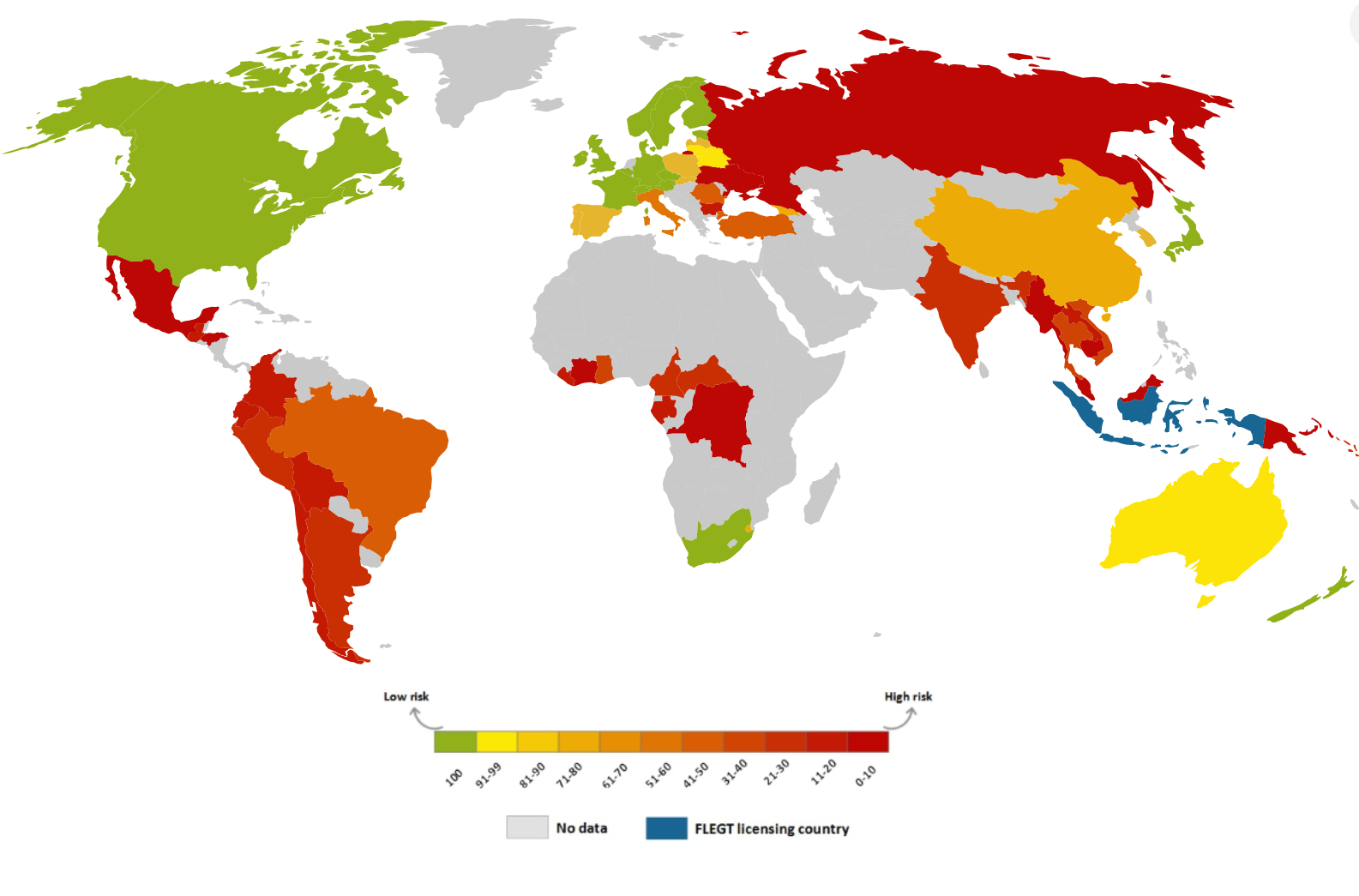

Vietnam’s forests haven’t been safe, too. For years, various cases of illegal timber trade have been reported in the country. According to international non-profit Preferred by Nature, the country logs 30,000-50,000 casesof forest violations per year. The organization also regards Vietnam as one of the most high-risk countries for illegal timber trade.

Even state-controlled media outlets in Vietnam sometimes publish opinion articles criticizing the Vietnamese government’s handling of environmental issues.

Risk map for the illegal timber trade in different countries. According to international non-profit Preferred by Nature, Vietnam is among the highest-risk countries in the world. (Graph by Preferred by Nature.)

Workers in Vietnam also face tremendous hardships and, in many cases, outrageous exploitation.

For example, cases of forced labor in drug detention centers have been reported. Individuals struggling with drug addiction were not only forced to work for free, but were also tortured. In the garment industry, child labor is a common practice. Even among the “normal” workers – those who are non-criminal adults and are able-bodied – mistreatment, underpayment, and lack of social security are also frequently reported.

It is not surprising, after all, that there are similar and even worse violations committed by Vietnamese companies abroad.

Unethical activities in Cameroon

Vietnamese companies are accused of various unethical activities in Cameroon, including violation of export laws, tax evasion, illegal harvesting, disregarding the illegal origin of timber, and abuse of workers.

In the name of profit, the companies casually engaged in these illegal activities. To maximize margins, the report says that the Vietnamese firms hired workers for years without a proper contract or social security guarantees. They frequently discriminated against, underpaid, and abused Cameroon workers.

The companies also avoided paying taxes in Cameroon by mostly conducting transactions with cash. From 2014 to 2017, around US$ 300 million went unaccounted for during the export of timber to Vietnam, according to the EIA investigation.

Alongside these violations, the companies also turned a blind eye to illegal timber, even if it came from terrorist organizations. In fact, according to EIA, the company Dai Loi was reportedly actively buying timber that originated from Hezbollah.

An informant from one of the private logging companies compared the way Vietnamese and French firms inspect timber in Cameroon: While the French tend to ask many questions regarding the origin of the timber — such as whether child labor was involved — the Vietnamese care only about whether there is documentation to bypass the Vietnamese customs or not, even if the timber was harvested illegally.

The informant said: “We wouldn’t care less about your wrongdoings. Just give me whatever papers that the customs require…”

Vietnamese customs also do not care about illegal logging because “it is like destroying forest in other people’s backyards, not in ours.”

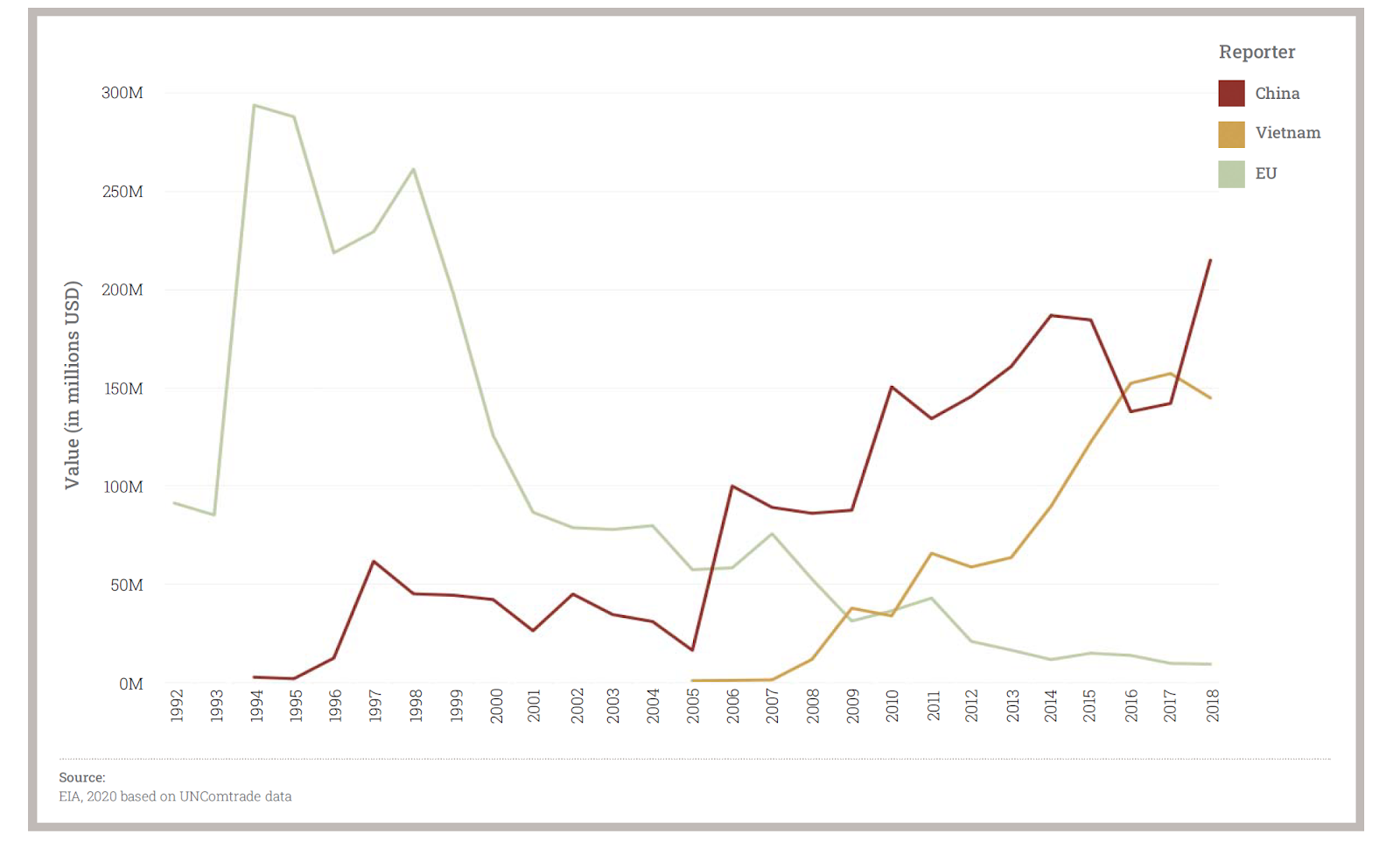

Imports of logs from Cameroon to China, Vietnam, and the EU during the period 1992-2018. In recent years, Vietnam has emerged as one of the largest importers of timber from Cameroon, using it for the construction of private structures and temples. Many Vietnamese timber companies moved from Laos and Cambodia to Cameroon due to its relaxed laws governing logging. (Graphic: EIA).

Policy recommendations for Vietnam

The EIA report recommends that the Vietnamese government do the bare minimum: Issue official acknowledgments of the loopholes in importing timber, followed by more effective regulations regarding fraudulent paperwork and financial transactions of private timber companies.

So far, half a year after the report’s release, no state-controlled media in Vietnam has reported on the situation. There have been no official statements and no apologies.

Based on his article on socialism, Nguyen Phu Trong argues that these flaws exist because the country is in the “transition period” to socialism. This means that the existing exploitation is not the government’s ideology, but rather the inevitable reality of the global capitalist, market-oriented economy. Furthermore, he says, these companies are private and not government-affiliated, so it is not the system’s fault.

Let us assume that this argument is true. If so, it is even more important and urgent for Vietnamese leaders and policymakers to acknowledge the unethical activities of these companies, and come up with more effective regulations to demonstrate their commitment to socialism – which, according to their own arguments, is supposed to be healthier for the environment, the economy, and workers.

Or are we supposed to wait endlessly for an unambiguous date of a successful transition to socialism? ●