Jammu & Kashmir is a union territory that has, for decades, been the subject of dispute between India and Pakistan. Previously, Article 370 of India’s Constitution gave Jammu & Kashmir special status, affording it a degree of self-autonomy: It had its own constitution and flag, and was able to govern over internal matters.

But in late 2019, India’s central government repealed Article 370, revoking the region’s special status. Almost immediately after, Jammu & Kashmir became a black box of sorts, with Internet, phone, and television signals disrupted. Aside from state-controlled channels of information, there was virtually no other way to know what was happening in the region.

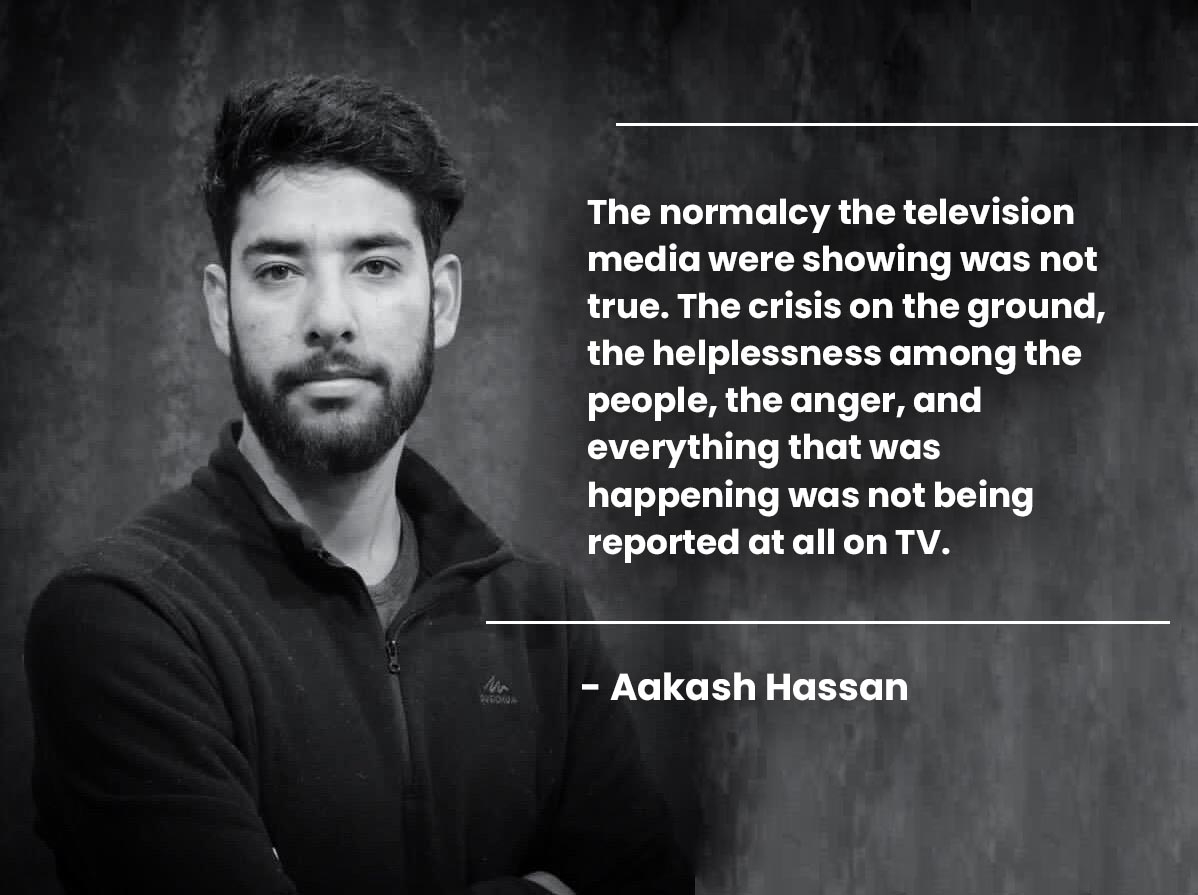

In this interview by writer Uday Rana, Kashmiri journalist Aakash Hassan walks us through the chaos and fear of the first few days after the revocation—and how local journalists refused to be defeated, fighting to tell crucial stories on the ground.

The transcript below has been edited for conciseness.

Uday Rana:

The word “lockdown” entered our lexicon in 2020, but there is one region in South Asia where “lockdown” is not a new word. In fact, it takes on a completely different meaning. I’m talking about Kashmir – the valley at the heart of one of the longest-running disputes and conflicts in the world.

On August 5, 2019, India’s Hindu Nationalist government revoked the special status and limited autonomy that Kashmir had had for the last 70 years. It put the region and its 8 million people under a strict military lockdown and a communications blackout where Internet, cell phone, and even SMS services were banned for at least two months.

And yet, journalists from Kashmir managed to get us stories from beyond India’s iron curtain. We’re here to talk about how they managed to do that.

Joining me from Srinagar, the capital of the Indian-administered region of Jammu & Kashmir, is journalist Aakash Hassan. Aakash is Kashmiri and an independent journalist. You can read his work in The Guardian, Al Jazeera, and a host of other international publications. Aakash, thank you so much for speaking to us and for being here.

Take me back to August 5. What were you doing when you heard the news and what was your first instinct as a reporter? How do you report an event like that?

Aakash Hassan:

Thanks for having me here.

On the morning of August 5, there was amazing calm when I left my house. I tried to drive to the press club, which is barely 4 kilometers away from my home. But I found that the entrance of the alley had been blocked by razor wire, so I had to pull my car over and start walking. It took me nearly 3 hours to reach the press club because of all the barricades and the checkpoints along the way.

There were military, paramilitary, and police fanned all across, and there was hardly a way to get through. I left home in the morning and I only reached the press club by noon, as did a few of my colleagues. It was only then, in the afternoon, that we found out through the television set in the press club that the special status had been revoked.

[But even in the previous days], there was already uneasy chaos. There were a lot of rumors that additional forces were being called into Kashmir, and the situation was as if we were preparing for war. For example, hospital rooftops were being painted with red crosses, and there were people coming to the government departments asking them to stockpile. A lot of these things were happening but no one was actually telling people what’s going to happen. Personally, like many other Kashmiris, all I could do was just to stockpile some vegetables and medicine, fuel up my car.

On the day itself, we only found out what has happened because I was able to watch it on the TV in the press club, but I know there were many in my neighborhood who couldn’t do that because the cable television was not working, and phone lines were down.

Rana:

So, then, at the press club, what happened? Because as a reporter, my first instinct would have been to get the story out. But how do you write a story when there’s no Internet, or there are no phone lines? What do you do, or how did reporting function in those early days?

Hassan:

Exactly. As a reporter, you start thinking that such a big thing has happened and you’re on the ground, but you are not even able to contact anyone.

Never mind your first job to report events, but even the most basic things like contacting your family to know how they’re doing, it seemed impossible at the time. In fact, it really was impossible.

I remember that day, with all my other colleagues gathered in the press club, we were all looking into the eyes of each other with helpless stares, knowing that we couldn’t do anything because there were just a few other people around, other than the military and paramilitary personnel, and that nothing was working. Eventually, we just stopped taking our phones out of our pockets. At the end of the day, we all left for our homes without any idea how we were going to file our stories. Back home, I pulled out my laptop and wrote the first draft of the story of what I saw that day.

On the third or fourth day, I managed to reach the office again and we were discussing what to do. I was working that time on the online arm of a television network, and one of our reporters there came up with the idea to capture a video of the laptop screen where the story was written and send the feed to the desk, where someone can write the story down again. That’s how I was able to send my first story, but most of the reporters were not as lucky as I was, and they could not do that.

At the time, there were also no landline phones working. Though some landline and cell phones of some officials were working, these were not accessible to reporters or civilians.

India’s Central Reserve Police Force start trickling into Kashmir days before the central government announces the revocation of Article 370, which allowed the Jammu & Kashmir region to enjoy a limited degree of autonomy.

Rana:

I have an image in my mind of journalists being hyper-competitive and trying to get the story first and competing with each other, but journalists also help each other out. How much of a role did this solidarity among Kashmiri journalists play in getting the story of Kashmir out? Were you all helping each other out?

Hassan:

Despite the extraordinary restrictions put by the government, at the end of the siege, the Kashmiri journalists were successful in telling the stories from the region, and it was possible only because of the cooperation and coordination between the journalists on the ground.

All the journalists would sit together, talk, share information, guide and help each other. We would give rides to those who were not working with big media houses and couldn’t afford a car.

I remember once we went to cover a story in south Kashmir, around 100 kilometers from Senegal. Only three journalists could afford a car at that time because of different reasons, but those three journalists pooled together around 15 people. That’s how journalists would help each other not only in terms of sharing information, but logistically. Everyone was supporting every other journalist in whatever means possible.

Rana:

The announcement [of the abrogation] was made in Delhi, in the Indian Parliament, and at first there was this daily attempt by the mainstream media to portray the sense of calm in Kashmir, that everybody was happy that there were no protests, and that most people actually support this effort by the government. How big of a gap was there in what was being said and reported in the media and how the people were actually feeling in Kashmir?

Hassan:

Honestly, television in mainland India was lying about Kashmir a hundred percent. I’ll categorize mainstream media into two categories: One is television media, which was completely lying. Another is print, which did a very good job, not a hundred percent fine, but they reported facts as they were. I wasn’t able to access the newspapers at the time, but later we saw that print media did a good job. Sometimes they couldn’t report the events as they happened, but we saw how different it was than television reporting.

The normalcy the television media were showing was not true. The crisis on the ground, the helplessness among the people, the anger, and everything that was happening was not being reported at all on TV.

There were protests. The BBC and other international media reported correctly, but then again television started showing fake news and were hiding facts on the ground. They were showing a fake normalcy. The TV reporters were being embedded with armed forces and government forces to show that everything was normal. They were taking footages from policemen. Yes, streets were empty, but they weren’t looking where the people were. They didn’t see that people have been locked down in their houses. They weren’t visiting places where there was a shortage of medicine, where people were crying, desperate to hear word from their loved ones who they weren’t able to communicate with due to the signal blackout.

Rana:

It’s now year two of the pandemic, so there’s a good chance that journalists from different parts of the world are going to have to operate under lockdown again. As a Kashmiri journalist who is not a stranger to curfews, restrictions, and communications blackout, what are some lockdown lessons that you have for journalists?

Hassan:

That’s a very important question, and I think what I would say is that people’s stories can be told even in lockdown if journalists start thinking out of the box. There should be cooperation between colleagues, that’s how we operate. We should help each other to disseminate the news.

For example, journalists in Kashmir pooled money to send one journalist to Delhi for the stories. We also realized the importance of flash drives and pen drives. We would write a story and save in our pen drives, then give it to the person near the airport, and he would take it to the outside world. These sorts of tools are actually very useful. More than that we have to think beyond sending stories on the internet or using the phone. We have to brainstorm and talk to each other. In gathering information on the ground, too, cooperation between journalists really helps.

Rana:

Thank you so much, Aakash for being here and speaking to us.

Hassan:

Thanks a lot, thanks a lot for having me

Photo credit for portrait: Aakash Hassan