When lawyer Zhang Keke visited Zhang Zhan, his client, in Pudong New District Detention Center in Shanghai, on January 13, 2021, he found a calm woman wearing pink pajamas who had seemingly accepted her fate.

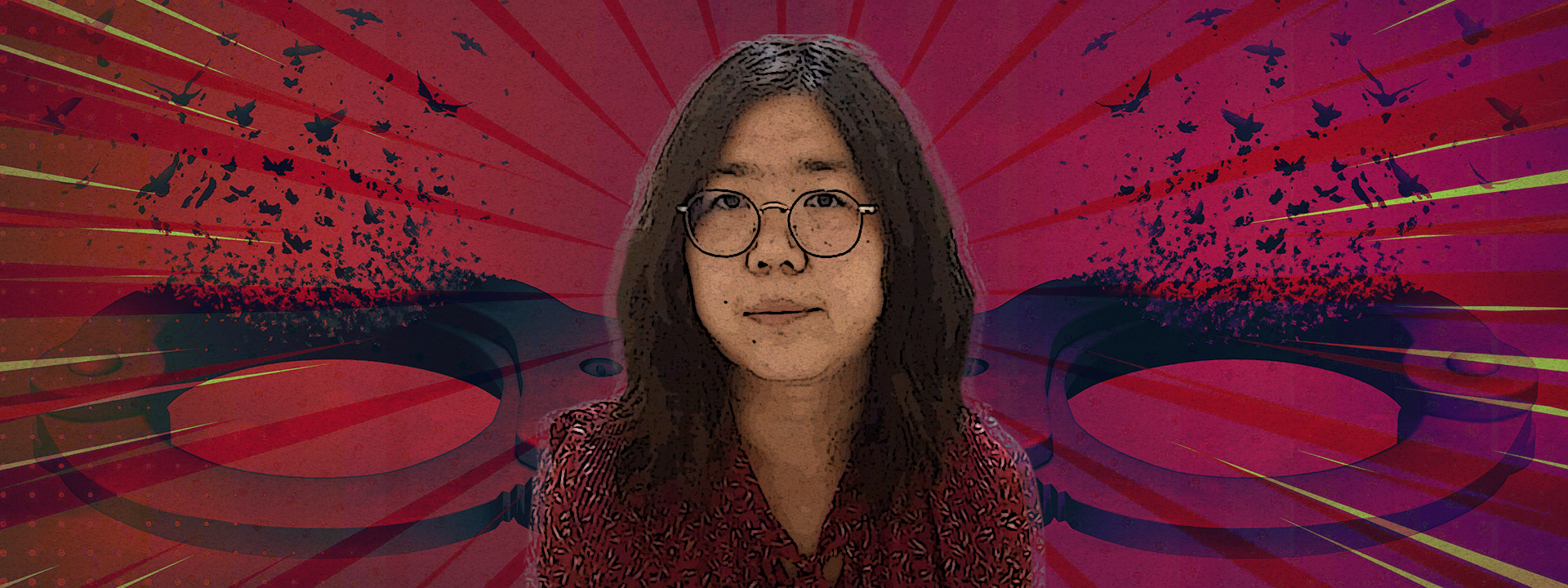

Zhang Zhan, a lawyer-turned-citizen-journalist, was sentenced to four years in prison by the Shanghai Pudong New District Court on December 28, 2020. She is the first citizen journalist in China to face legal proceedings for her reporting.

Her reports from Wuhan at the start of the coronavirus pandemic offered the Chinese people and the outside world rare glimpses into the real situation on the ground. “Citizen journalists were the primary, if not the only, source of uncensored and first-hand information about the COVID-19 outbreak in China,” reports Amnesty International.

However, the authorities found Zhang Zhan guilty of “fabricating lies and spreading false information.” This is a broadly defined offense often used by the police to stifle dissent, reports the South China Morning Post.

Zhang Zhan’s imprisonment shows the determination of the Chinese authorities to rewrite the narrative of how the government managed the coronavirus outbreak. The state’s official line purports to show strong governance by the Chinese Community Party and praises the dedication of the medical staff in Wuhan. The authorities silence the voices of critics like Zhang Zhan and other citizen journalists such as Chen Qiushi, Fang Bin, and Li Zehua.

Zhang Zhan’s reports from Wuhan offered the Chinese people and the outside world rare glimpses into the real situation at the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic.

A vocal critic

At the start of the coronavirus pandemic, Zhang Zhan went to Wuhan, where she produced and uploaded 122 videos to YouTube consisting of “interviews with residents, commentary and footage of a crematorium, train stations, hospitals, and the Wuhan Institute of Virology,” reports ABC News. “She used online platforms (including WeChat, Twitter, and YouTube) to report on the detention of other independent reporters as well as the harassment of victims’ families,” reports Amnesty International. She also wrote essays critical of the Chinese authorities’ handling of the coronavirus outbreak, including the draconian lockdown of millions of people and the skyrocketing food prices.

Friends familiar with her reporting in Wuhan worried for Zhang Zhan’s safety as she documented the situation on the ground. Li Dawei said, “I talked to her every day and kept asking her to be cautious because the real number of coronavirus deaths is the top secret of the authorities.”

Her friends urged Zhang Zhan to leave Wuhan. Liang Yun* and Fan Fan* warned her that the authorities were collecting evidence against her by interrogating those who had shared her videos or essays. The citizen journalist refused to leave, though. Instead, she even went to the police station to look for Fang Bin.

“Zhang Zhan was aware of the danger: the danger to be infected and the risk of being suppressed,” said Li Dawei. “For the former, she chose to record bravely; for the latter, she chose to face it fearlessly.”

Fan Fan saved a screenshot of Zhan Zhang’s essay, which showed her determination to pursue her cause: “Neither I nor this country can step back in the face of such crisis.”

Friends said that she is determined to be a martyr. They shared one of her censored essays in which Zhan Zhang wrote, “I know this country needs dedication, sacrifice, blood, and flesh for peace and freedom.”

On the date she was sentenced, dozens of her friends assembled outside the courthouse to show their support. The police outnumbered them and forcibly took them to different police stations. Nine people were interrogated for hours, according to Li, who was quizzed for four hours. Reporters were pushed away by security officials.

Li, considered the ringleader of the assembly, was kept on house arrest for a day. Later, upon Li’s return to his hometown of Tian Shui, he was placed under house arrest for nine days. He considered his detention a minor inconvenience. “Compared to Zhang Zhan’s suffering, what we suffered is not worth mentioning,” he said.

The authorities praise the dedication of the medical staff in Wuhan while silencing the voices of critics such as citizen journalists.

An idealist

No one knows why or when Zhang Zhan became interested in becoming a lawyer. Armed with a master’s degree in finance, she worked as an investment manager at securities firms in Shanghai from 2011 to 2016.

She resigned from her job in June 2016 and received her license to practice law in 2017. Jiang Zhaojun, a criminal defense attorney, had planned to invite Zhang Zhan to join his law firm. Jiang said he was surprised that a financial professional would quit such a well-paying job to become a lawyer. She seemed to care more about fairness and justice than she did about money and status.

However, in 2017, Shanghai issued a stringent regulation prohibiting lawyers from commenting on ongoing cases, co-signing and publishing open letters, organizing online gatherings, and expressing views critical of the Communist Party and the government. A petition against the regulation was launched, and Zhang Zhan was one of 168 lawyers who signed it. As a result, she was interrogated several times and eventually had her lawyer’s license revoked, either in 2017 or 2018. Her friends said the court files did not indicate when the revocation happened.

Lawyers in China frequently face harassment, disbarment, and imprisonment for their work. After Chinese President Xi Jinping came to power in 2012, blistering campaigns against human rights lawyers were waged, such as the 709 Crackdown in 2015 and 12.26 citizen case in 2019. In both cases, hundreds of lawyers were detained or had their licenses revoked.

“With her brave character and strong ability, I am sure that she would represent all kinds of cases and would adhere to the rule of law and defend human rights,” said Jiang. “But it is a pity that she didn’t have the chance to practice law and ended up a citizen journalist in prison.”

A feisty warrior

On December 28, 2020, Zhan Zhang was wheeled to court in a wheelchair. Lawyer Zhang Keke recalled that though the activist was physically weak, her thinking was clear. During the trial, she barely spoke.

She only questioned the judge, “Don’t you think your conscience will tell you it’s wrong if you put me in the dock? This is a court to judge you, not me.”

When the lawyer visited Zhang Zhan in January, his client said that the current laws in China are not in line with democratic principles and that she refused to cooperate with the authorities. “Zhang Zhan is tough and stubborn,” said Zhang Keke. “She rarely cries, until I read her some cards from her friends and supporters.” One card read, “You are a grain of wheat, a beam of light, and a million seeds.”

The odds may not be in Zhang Zhan’s favor. She has been weakened by the hunger strike that she began in June 2020 to protest her detention. Still, the citizen journalist remains resolute in her fight for truth and justice.

Her friend Li Dawei and another source who requested anonymity said that Zhang Zhan has written letters exposing the false propaganda spread about the pandemic by government officials and the media. Zhang Keke said that Zhang Zhan told him that, every morning and night at the detention center, she spoke volubly about the dangers of totalitarianism in China and the lack of freedom of expression.

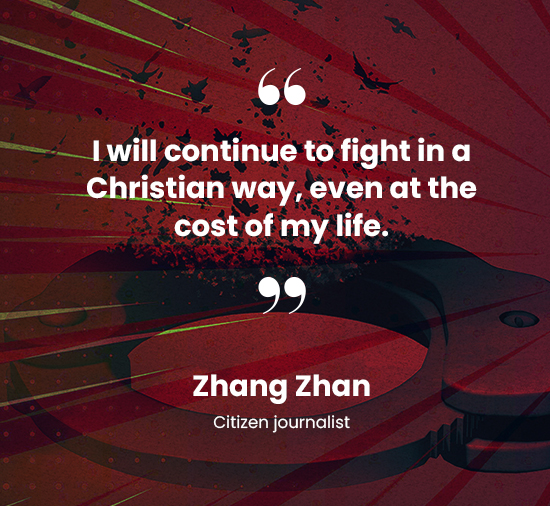

Zhang Keke also vividly remembers Zhang Zhan’s words to him: “I will continue to fight in a Christian way, even at the cost of my life. I will make them [the regime] repent, and I will continue to pray for God’s great love to give guidance.” ●

* Pseudonyms have been used to protect the identities of the interviewees.

Leila Coman is an independent journalist based in China who covers social issues and human rights.