The year 2020 was marked by a sharp rise in human rights violations in India. Some violations were executed by random vigilante groups, while others had state backing and sanction.

In this interview by Insiyah Vahanvaty, a writer and the founder of GoondaRaj, a social justice initiative and podcast, Mohsin Raza Khan examines the reasons behind the culture of impunity that prevails in India. Khan is Associate Professor and the head of the Center for a New South Asia at the Jindal School of International Affairs, O.P. Jindal Global University in India.

The transcript below has been edited for conciseness.

INSIYAH VAHANVATY:

A few violations shook the world and made it to international news. One such case took place in Tamil Nadu on the 19th of June [2020]. A father-son duo named P. Jeyaraj and J. Bennix, who run a small mobile repair shop, were arrested on the charge of violating the [COVID-19] lockdown and keeping the shop open too late. Following the arrest were all kinds of torture at the hands of the local police, which resulted in the custodial deaths of both men.

Other violations include domestic abuse, which is reportedly at an all-time high and rising. Human rights activist Kavita Krishnan is the secretary of the All India Progressive Women Association. She said that vulnerable women could have moved to safer places if the government had given some warning of the lockdown. At the moment, there seems to be nothing to do except to help rescue women who reach out on an emergency basis.

More hate crimes were reported. Many communities have been wrongly blamed for spreading the virus. We saw vigilantes attack and humiliate people from northeast India, calling them names like “corona” simply because they look more Chinese than mainstream Indians. Many northeasterners report being evicted, with shopkeepers refusing to sell them rations, and being abused on the streets.

Indian Muslims faced a similar fate after the Tablighi Jamaat incident, where some people who attended the religious gathering were found to have tested positive. This resulted in a nationwide targeting of Muslims, many of whom found themselves victims of hate crimes.

There were incidences of lynching, of vegetable sellers not being allowed to sell in Hindu neighborhoods, and of Muslim students being evicted from their rented homes. Words like “corona jihad” and “super spreaders” were used exclusively for these communities to degrade and humiliate them.

What is interesting is that not a single one of these cases resulted in the arrest of the perpetrator of the crime. All of the offenders have been allowed to go scot-free, a factor that might explain the growing culture of impunity amongst violators of human rights in India.

What is interesting is that not a single one of these cases resulted in the arrest of the perpetrator of the crime. All of the offenders have been allowed to go scot-free, a factor that might explain the growing culture of impunity amongst violators of human rights in India.

I have with me today Mohsin Raza Khan, who will do a deep dive into the factors that contribute to this nationwide culture of impunity.

MOHSIN RAZA KHAN:

Hi, Insiyah. Thanks for inviting me to your show, especially on such an important topic.

VAHANVATY:

Mohsin, it’s a pleasure to have you on today to speak about this culture of impunity that exists in India. Let’s start by talking about the reasons that have led to this culture and what it has meant during the lockdown.

KHAN:

This culture of impunity exists because of the lack of rule of law. This includes both a dysfunctional judicial system as well as a dysfunctional policing system. If there is no punishment for any crime and people feel they can get away with it, then you will have impunity.

Now the problem is, if you don’t have the rule of law, then what you have is the belief that might is right — power and connections are the only things that count. The reason the system is this way is because the rulers want it and the voters, that is majority of the public, also does not mind.

The rulers, the politicians, prefer it this way because whoever is in power can then utilize the police for their own benefit and for punishing their opponents. Hence, they do not want accountability. They want police who are accountable to them and a judiciary that can be manipulated.

Part of the reason there is such huge police impunity is that we don’t have a law by which any citizen can freely prosecute a police officer or even a government servant. This is not so in the West, where police officers can easily be prosecuted by common citizens. We saw this in the cases of police brutality in the U.S. In India, you have to get special permission from the ministries, which is something they never give.

A second problem with the police is that it is poorly funded and offers very poor salaries. Therefore, you get low-quality recruits.

A third problem is because of a low budget. India has among the world’s lowest police-to-population ratio. All of these problems are there because India is largely a developing country, and therefore resources are scarce, and also because this is not a priority for either the politicians or the voters.

We don’t have any law on command responsibility either. So, in cases of mass violence, for example, command responsibility says that the person at the top will be prosecuted if there is violence under you in that region if you were the person in charge.

The voters in Indian society are segmented. We have a segmented society, where each section wants to grab a share of power. And whoever is more powerful or is able to leverage their position is then able to appropriate all those goods.

There are two kinds of goods according to economists: private goods and public goods. Public goods are those goods whose consumption by one does not reduce their consumption by another. For example, national security and a clean environment are public goods, as are domestic security and law and order.

Unfortunately, in India — and in other developing countries such as Pakistan and Bangladesh — many public goods have become private goods. That is, security will be provided to some and not to others, depending on your power.

In India and other developing countries, group identity matters: which caste you belong to and which clan. But in a modern industrialized society, group identity matters less. As citizens become individualized, they demand protection from the state.

In India, we haven’t reached that stage. We still demand group rights. If you can get security as a group or as a family, that’s fine. But as individuals, you don’t have those social and government systems. The state is poor because the country is poor and, therefore, the rule of law is bad.

What I am saying is, partly the way we are is because of our level of economic development and part of it is the way the politicians and the voters prefer it. If this were really an important and big demand, it would have by now been solved because it would have become an electoral issue.

VAHANVATY:

During the lockdown and in the months that followed, we saw a rise in the number of cases that were of a criminal nature. Do you think that this breakdown of the law has intensified during the pandemic?

KHAN:

KHAN:

Yes, it has intensified during the pandemic because the police have been given more freedom to use violence by the state.

I think generally the Indian judiciary is also at fault in many of these cases. For example, in the Bennix-Jeyaraj case, the judicial magistrate who was responsible allowed the police to retain custody of the father and his son.

We have to build public discourse against these human rights violations in favor of police reform and judicial reform. This public discourse then has to translate into pressuring political parties to make it a part of their manifestos. It is easier to work with the party that is in opposition because whoever is in power doesn’t want to do these police and judicial reforms.

But whoever is in opposition, because they are themselves victims, are more willing to listen. Then they can be asked to put it in their manifestos and then shamed once they’re in power to make them go ahead with it. But for that, public pressure will have to be built up.

A discourse will have to be developed. It cannot be done purely by legal means or other means. For example, commissions have issued many reports on police reform, but no reform gets implemented because it is not in the interests of state governments. In fact, even the Supreme Court! I think it’s called the (R.P.) Singh case. It has passed a requirement that state governments conduct three big reforms, police reforms that were asked for but none of the states have followed through.

The vigilantes act with impunity because they know that the government and the police are on their side. The reason vigilantes feel so safe, say, with respect to Muslims, is that Muslims are being targeted by the Bharatiya Janata Party, the ruling party, and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, a powerful group. [The group is “India’s most prominent proponent of Hindutva — Hindu-ness and the idea that India should be a ‘Hindu nation,’” reports NPR.]

So, if you were to target people from the upper castes — or even Sikhs, Christians, tribal people, and Dalits — the police will respond. Because these groups matter to the ruling party, you will have blowback.

But if you target Muslims, this is exactly what the politicians want. It polarizes society, and this helps them get votes.

May 14, 2020. The police wield “lathis” — in this case, polycarbonate pipes — to disperse a crowd outside of a railway station in Mumbai. The use of these batons has been criticized as brutal.

VAHANVATY:

Yes, I remember we saw these during the Tablighi Jamaat incident as well, after which the Muslim community was targeted for spreading the virus.

KHAN:

The government in India is under watch by organizations abroad because of its discriminatory behavior. There is an organization called Genocide Watch in the U.S. that has placed India in a high-risk category because of the [government’s] behavior in Assam and Kashmir.

During the pandemic, many Muslims suffered abuse — beaten for trying to sell vegetables, or in the case of the Tablighi Jamaat, put in jail before the accusations were made. The anti-Muslim prejudice was amplified by media organizations.

First, the directive came from the home ministry in releasing the exact religion of these people. Then strategic leaks were created to say that they were behaving poorly, but little or no evidence was provided, and then these TV channels played them on a loop.

This created a scary situation. I was in rural Haryana, where my university is located, and when I would do my shopping, I would hear wild rumors against Muslims — and this was in an area where there are hardly any Muslims. Maybe not even one percent because most of the Muslims in this area were ethnically cleansed during [the partition of the Indian subcontinent into separate states in 1947]. We would hear vile rumors that Muslims are spreading this disease. There was a great fear in my mind that violence would break out any moment.

VAHANVATY:

This sounds like a tinderbox! The fact that most Indians live feeling unsafe at some level is quite concerning. Do you think we need more reforms or just better implementation of existing reforms?

KHAN:

I think we need better implementation of the laws which exist, but I think we also need reforms. We need judicial reforms; we need police reforms urgently. Without that, you will not see changes.

The police have to be made responsible to citizens. It has to be freed from political control. Police recruitment and training have to be changed. The same thing goes for the judiciary. There is a need for better-trained judges and simplified court procedures.

All those reforms are required but also, of course, they require political will. And political will only comes from voter demand.

VAHANVATY:

Do you think we should look at a completely different system then, since the one that we have is obviously so flawed?

KHAN:

Whenever you want something new, first you have to start with reforming what exists. You can’t just throw this out, lock, stock, and barrel, because then you would be left with a vacuum. So you would have to reform this system. This can only be done in gradual steps because you might end up otherwise making more severe mistakes in the process of change.

If you want a whole field change, you might end up creating a greater hell. Public policy is not done through these huge changes. They usually lead to more problems as we have seen in the demonetization [of the Indian currency in circulation in 2016, which discontinued all ₹500 and ₹1,000 banknotes].

VAHANVATY:

Thank you, Mohsin, for coming on today and speaking about the subject. The pandemic has certainly brought this problem into sharper focus, but it’s something that needs to be seen and dealt with in a more holistic manner, you know, as you said, starting with serious reforms and honest political will.

KHAN:

I would like to thank you, Insiyah, for bringing me on to your podcast on such a critical topic, a topic that is also deeply close to my heart and I’m sure to the hearts of all people who believe in human rights. ●

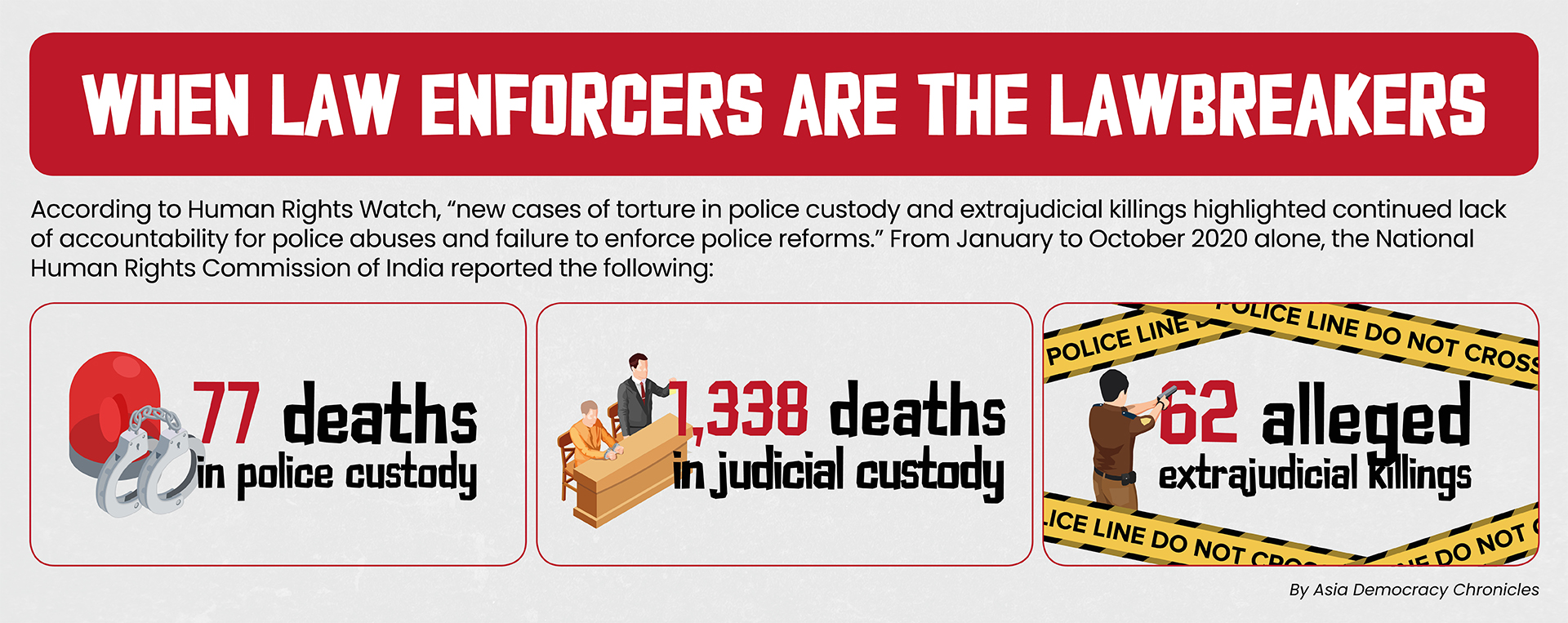

Source: Human Rights Watch