Editor’s Note: Despite the pandemic, Singapore pushed ahead with its general election on July 10 amid concerns that the government’s top priority should have been quelling the coronavirus spread, not getting a “full fresh five-year mandate” while the end of its term was still a full nine months away. After all, the deadly virus has affected tens of thousands of people in the city-state, the majority of whom are migrant workers living cheek by jowl in communal quarters. But the ruling People’s Action Party, led by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, would not be swayed otherwise from its firm resolve to pursue its political agenda, “putting its own political future above the safety and well-being of Singaporeans,” in the words of the opposition Singapore Democratic Party.

In the days leading to the vote, the Singapore government had its hands full monitoring and fighting “disinformation” as defined in its playbook, and with zero tolerance for “other” narratives — a stance that will continue long after the pandemic.

In this explainer series, civil rights advocate Jolovan Wham provides a detailed account of how the government has perpetuated a single narrative through much of Singapore’s history, and how the latest draconian law against fake news is being weaponized to stifle free speech.

Part 1: From backwater island to first-world country that silences critics

When Singaporean historian Thum Ping Tjin was called to testify before the parliamentary Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods in March 2018, he was not expecting to be questioned for nearly six hours on a topic which had little relevance to the issue at hand. Not only did the island republic’s Law and Home Affairs minister K. Shanmugam cast doubt on Thum’s academic credentials, he was also accused of poor scholarship. “I’m suggesting to you, based on what you have said to us, what we have seen is not scholarship, but sophistry,” the minister said. Thum disputed it.

The Select Committee’s hearing on online falsehoods was convened in January 2018 to examine the extent to which disinformation and misinformation, or “fake news,” was a problem in Singapore. It invited members of the public to give written submissions and propose solutions to tackle this “global scourge.” Those who were willing to give oral testimonies before the committee were invited to do so. The committee consisted largely of Singapore’s ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) and had one member from Singapore’s only opposition party in parliament.

Thum’s five-page submission to the committee dealt largely with how online disinformation did not pose a serious threat to Singapore and recommended that the government increase media literacy and public education to tackle the issue, instead of enacting new laws which could stifle free speech. However, the submission included one paragraph in which Thum accused the late Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew of creating fake news when he ordered the torture and imprisonment of political dissidents during the 1960s under the guise of dealing with a communist insurgency. Thum had argued that the real reason behind the detentions was that Lee had wanted to get rid of his political opponents. This argument prompted a six-hour interrogation by the law minister.

Following his testimony, Thum spoke to the press, saying “he did not expect his work to be ‘dissected’ to such a degree. In some ways, it’s very flattering that the Minister of Law and Home Affairs takes such a keen interest in my work,” Yahoo! Singapore reported.

“’What other academic in what other country would have a minister grilling him for six hours about one article?’ he said wryly.”

Single narrative and the perpetuation of one-party rule

The story of Singapore’s transition from a third- to first-world country is one which is firmly entrenched in the country’s history and consciousness. The pioneer leaders of the ruling PAP are credited with leading the ex-British colony from being a poverty-stricken backwater to a first-rate global city. It was their sacrifices which had given the ruling party its current political legitimacy. As a small island nation-state, Singapore’s unexpected independence in 1965 left it vulnerable on many fronts. Amid the volatility, not only did the newly-elected PAP have to lift its people out of poverty and ensure the progress of the nation, but it also had to battle communist insurgencies which threatened to subvert and destabilize the young nation. It was Lee Kuan Yew’s foresight and heroic leadership which helped the country overcome these challenges.

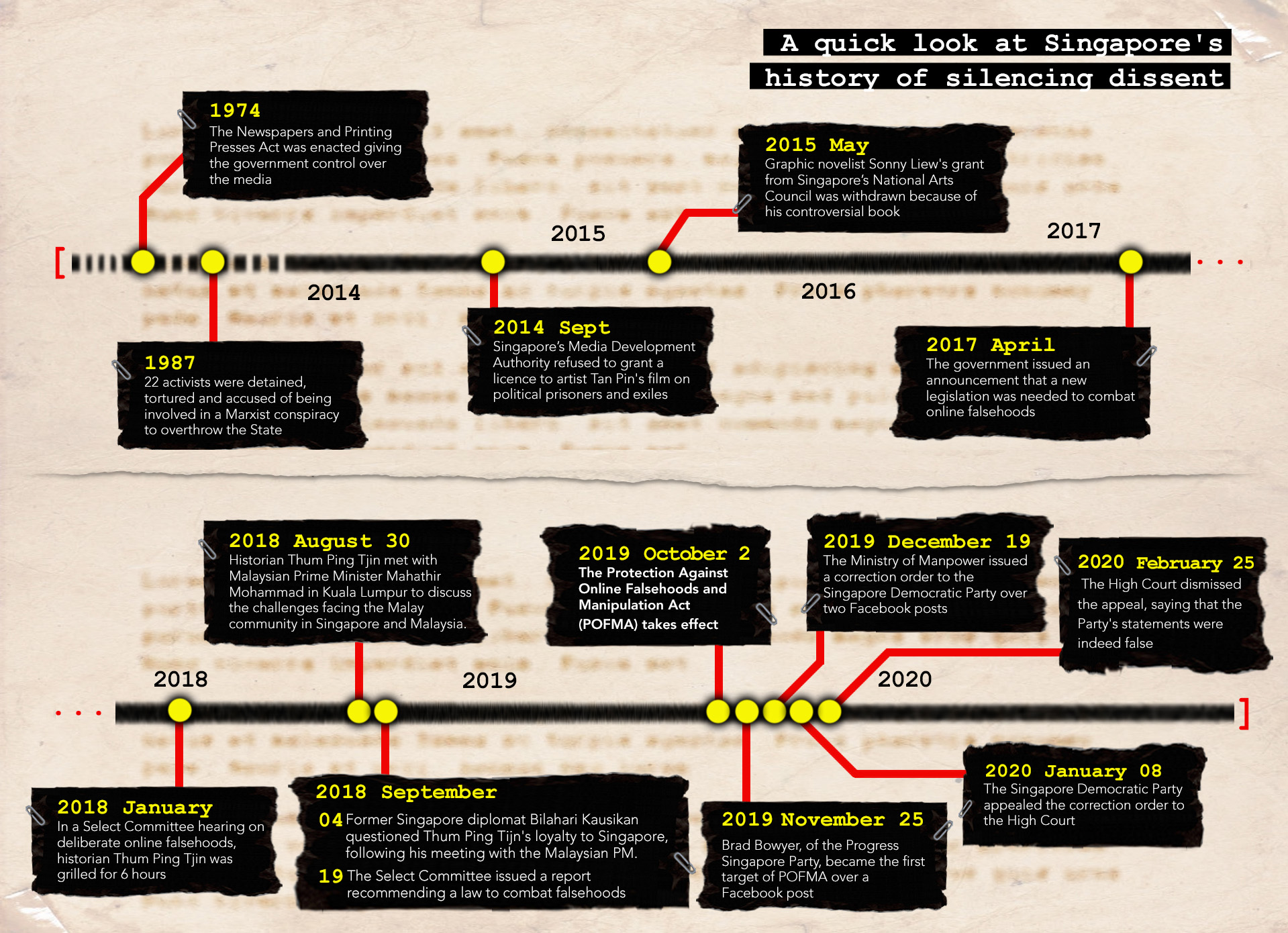

As the PAP consolidated its power, this narrative started to have a stranglehold in the national discourse. Newspapers which were critical of the government and the ruling party were shut down. The Newspapers and Printing Presses Act was enacted in 1974 to give the government control over the media by making it mandatory for the committee of all news agencies to be approved by the Minister.

A wave of security operations in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s also led to more activists, unionists, and dissidents being tortured and detained without trial. The most well-known of these led to the detention of 22 activists in 1987 who were accused of involvement in a Marxist conspiracy to overthrow the State. These crackdowns were often carried out under the guise of protecting national security, but no reliable or independent evidence has been presented to validate these accusations.

These activists were arrested, tortured, and detained without trial. The accusations hurled against them were similar to those lobbed at the activists targeted during the security crackdown in the 1960s except that this time, the individuals rounded up by security forces were said to be using “new techniques and methods” such as spreading their doctrine and agenda through the Catholic church and other religious organizations. They were forced to sign confessions and appear on national television to declare that they were reformed subversives with the intention of overthrowing the government. State media uncritically published the government’s account of the crackdown, and it continues to parrot the government’s line.

Trade unions were brought under the thumb of the government-controlled National Trades Union Congress while those who instigated and organized strikes were thrown in jail. Grassroots organizations and neighborhood residential committees were brought under the control of the People’s Association, an umbrella organization chaired by the Prime Minister. Opposition politicians were also sued to bankruptcy. The message was clear: dissent and alternative discourses which threatened the ruling party would not be tolerated.

This narrative is being challenged by historians like Thum. In the past five years, he has been actively involved in civil society events and academic presentations where he has questioned these foundational myths. The security crackdown by the PAP-run government in the 1960s known as Operation Coldstore, which led to the arrest and detention without trial of at least 100 individuals, has always been justified because of the threat of subversion posed by the Malayan Communist Party.

According to Thum, declassified Special Branch documents revealed that the party never had a significant foothold in Singapore. British documents did not reveal communism to be a significant threat, nor did investigations after the arrests of the activists and politicians point to any evidence that the detainees were involved in a conspiracy to subvert the State. Thum believes that the arrests and detention were an excuse for Lee Kuan Yew to eradicate his political enemies.

Singapore’s political leadership uses a combination of control over its key democratic institutions and laws which stifle dissent to ensure not only a compliant populace but also to create an environment which prevents alternative narratives from taking root.

Similarly, the account of activists who were accused of trying to overthrow the government in what has been dubbed a Marxist conspiracy is being challenged. In the last decade, former detainees have been organizing themselves to seek justice. Function 8, a group set up by survivors of the 1987 arrests and their sympathizers, has been organizing film screenings and similarly-oriented events, as well as publishing books to counter the State narrative. Ex-detainees of Operation Coldstore have also started to speak out. These acts of resistance have not gone unnoticed by the government.

A public talk at Singapore’s National library stirred controversy when Vincent Cheng, one of the former detainees accused of involvement in a Marxist conspiracy, was banned from speaking. “Untracing the Conspiracy,” a film by independent director Jason Soo, was slapped with an R21 rating, restricting its viewership to those who were 21 and above. Another film which presented a critical perspective on Operation Coldstore was banned completely from public screening.

Singapore’s political leadership uses a combination of control over its key democratic institutions and laws which stifle dissent to ensure not only a compliant populace but also to create an environment that prevents alternative narratives from taking root. Not only do PAP leaders resort to civil suits to sue opposition politicians and activists to bankruptcy; they also enact laws which make dissent costly. Protests outside of a government-designated park are de facto illegal, and critical discussions on race and religion result in police investigations. Academics have reported losing their jobs and being censured for their involvement in activism, politics, or discussions about sensitive social issues.

In September 2019, Yale-NUS prevented a playwright from conducting a workshop called “Dissent and Resistance” on its campus, citing concerns around “partisan politics” and potential trouble for its international students. Charities and welfare groups dare not publicly criticize the government for fear of losing funds and patronage from the elite. A social worker from a family service center revealed that it is difficult for many of her colleagues and peers in other organizations to speak up publicly about government policies affecting the poor and marginalized communities as they may lose their jobs.

Art groups and artists routinely skirt the boundaries of the country’s tough censorship laws and cannot express themselves freely for fear of losing government funding, which many of them rely on.

A publishing grant from the National Arts Council (NAC) for Sonny Liew’s graphic novel, “The Art of Charlie Hock Chye,” was withdrawn in May 2015, ahead of the book’s launch, owing to its controversial content. The book presented a critical view of Singapore’s political development and depicted Singapore’s first prime minister, Lee Kuan Yew, as a ruthless boss of a company called Sinkapor Inks. A NAC spokesperson said the book “potentially undermines the authority of legitimacy of the Government and its public institutions and thus breaches our funding guidelines.”

Filmmaker Tan Pin Pin faced similar problems when she attempted to release her documentary in Singapore. “To Singapore With Love” is a film about political prisoners and exiles, many of whom were accused of being communists during the 1950s and 1960s. The film explores their lives, memories, and hopes for the future. Many of them fled to avoid being detained under the Internal Security Act. Singapore’s Media Development Authority (MDA) refused to grant the film a license on the grounds that it undermined national security. That means it could not be shown in Singapore. According to MDA, “The individuals in the film have given distorted and untruthful accounts of how they came to leave Singapore and remain outside Singapore.”

Filmmaker Jason Soo received the same response from the authorities when he submitted his film about ex-political detainees involved in the alleged Marxist conspiracy. He was told that the film did not provide a “balanced account of history.” Responding to this assessment, Soo says: “But the whole point is that there is no balance when oppression and injustice occurs. The film does not present a balanced account of history because the film is the balance to a historical oppression.”

Laws such as the Films Act also deter filmmakers from exploring alternative political narratives. Party political films are banned. Such films are defined as any film that “relate wholly or mainly to politics in Singapore,” or “directed towards a political end in Singapore.” In 2005, documentary filmmaker Martyn See was placed under investigation for making a film about opposition politician Chee Soon Juan. He was threatened with prosecution and had his film equipment seized by the police. Under the Films Act, officers can enter homes and seize property without a warrant.

Part 2: Online falsehoods: A genuine problem or a pretext to crackdown on free speech?

Even before the Select Committee had been convened to determine whether new legislation was needed to combat online falsehoods, the Law and Home Affairs minister had already announced to the public that such a law would most likely be introduced the following year, leaving some critics to conclude that the Committee’s proceedings to be conducted for this purpose would be a sham. A call for submissions by the public was made in which non-government organizations (NGOs), individuals, think tanks, media organizations, and academics were sought for their views on how Singapore can prevent and combat online falsehoods. A paper submitted by the Community Action Network, an NGO which advocates for freedom of expression, argued that many of Singapore’s existing laws were already sufficient to combat falsehoods. Other individuals and NGOs who submitted their views to the Committee made the same point.

Riding the tide of rising global concern about falsehoods, the government justified the need for this law. A Green Paper released to the public cited examples from other countries where falsehoods had been used to undermine elections and exploited social and religious fault lines. But the government provided no evidence that such threats were prevalent in the Singapore context and ignored the fact that previous instances where falsehoods were circulated were quickly addressed, either through law enforcement or clarifications through the country’s influential State media. It also ignored the fact that Singapore already had a range of laws which can be used to punish the purveyors of falsehoods and those who undermine national security. Examples of such laws were the Sedition Act, Penal Code, Internal Security Act, and the Computer Misuse Act. Law minister K. Shanmugam dismissed criticism that the new law would have a chilling effect on free speech, arguing that it was needed to protect the city-state’s democratic institutions, seeing how they were easily undermined in other countries.

Six months after concluding its hearings, the Select Committee issued a report and, unsurprisingly, recommended that the government enact a law to combat falsehoods. The Protection Against Online Falsehoods and Manipulation (POFMA) bill was introduced and approved within a month by a PAP-dominated parliament. The law allows any minister in government to order “corrections” to online content deemed to be false in Singapore and in other countries as long as it is being communicated in Singapore, and that it is in the public interest to ensure such falsehood is corrected.

Public interest is defined vaguely to include protecting “friendly relations” with other countries; preventing the diminution of public confidence in the government, any statutory board or part of the government; or protecting “public tranquility.” The law was criticized for being too vague about the definition of falsehood and for giving the ministers in government arbitrary powers to decide on what is false. Appeals against a minister’s order to take down a post can only be made through the High Court, which may result in a costly and protracted public process which an ordinary citizen is unlikely to pursue.

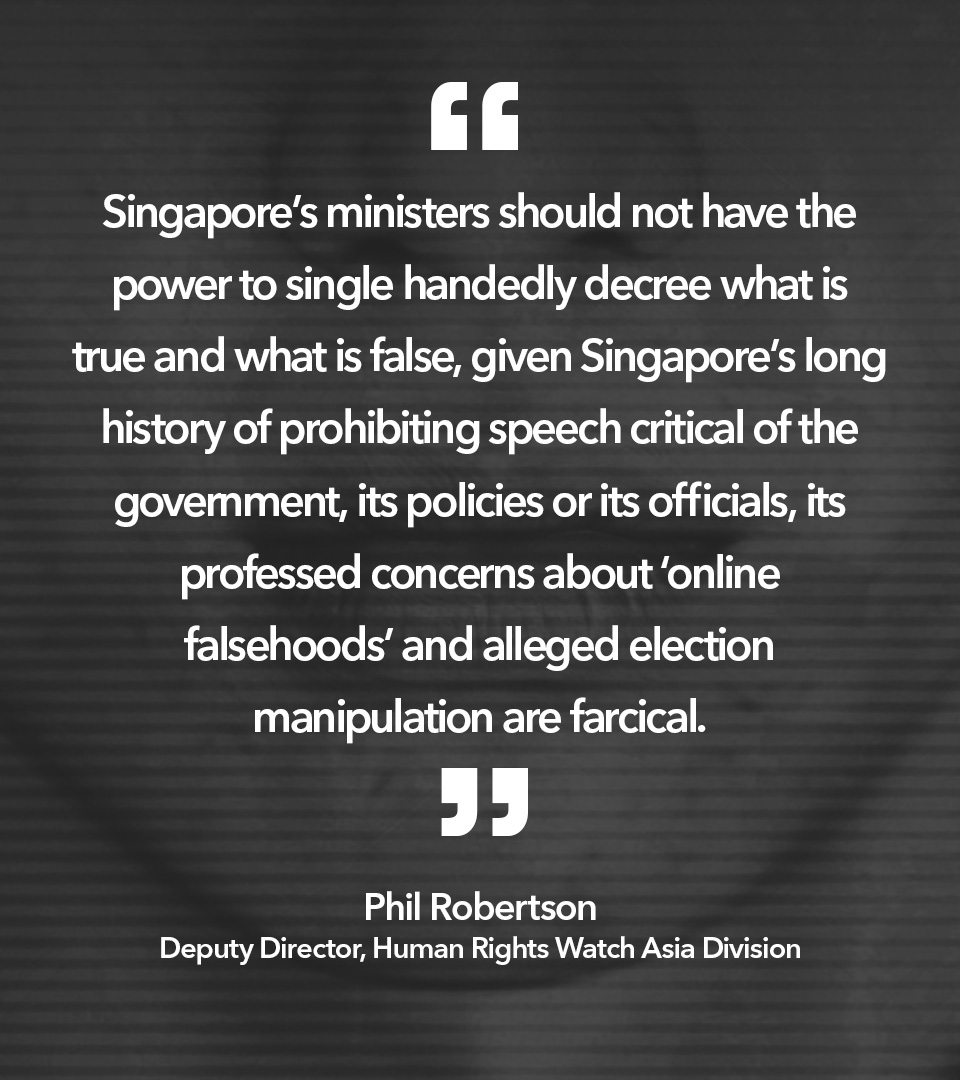

Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch Asia Division, said, “Singapore’s ministers should not have the power to single-handedly decree what is true and what is false, given Singapore’s long history of prohibiting speech critical of the government, its policies or its officials, its professed concerns about “online falsehoods” and alleged election manipulation are farcical.”

Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch Asia Division, said, “Singapore’s ministers should not have the power to single-handedly decree what is true and what is false, given Singapore’s long history of prohibiting speech critical of the government, its policies or its officials, its professed concerns about “online falsehoods” and alleged election manipulation are farcical.”

Since the passage of the law, POFMA orders have been issued mostly to activists as well as opposition political parties and organizations, reinforcing the belief that the law was meant to target critics of the government and the ruling party. Opposition politician Brad Bowyer became the first target of the law when he was asked to post a correction on his Facebook page over comments he had made about Singapore’s government-linked companies. He had questioned the independence of Temasek Holdings, the company which manages Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund, and the independence of Singapore’s other government-linked companies. In response, the Ministry of Finance issued a press statement claiming that Bowyer’s post contained “false statements of fact” and “undermines public trust in the government.” The Ministry went on to claim, without irony, that the government is not involved in the investment decisions of government-linked companies. This, despite the fact that the Prime Minister’s wife, Ho Ching, is the chief executive officer of the country’s sovereign wealth fund, and the current members of the Parliament and the sitting ministers of the ruling party are board members in many of these companies.

Nowhere was the threat to freedom of expression more evident in the government’s use of law than in a case involving the Malaysian civil rights group, Lawyers for Liberty (LFL). In January this year, LFL said a source from the prison service told them that prison officers were instructed to carry out a “brutal procedure” for capital punishment cases in which the rope broke when someone on death row was hanged. It alleged that the prison officers were instructed to pull the prisoner in opposite directions and then kick the back of his neck with great force to break it.

When the news of this practice broke, independent journalist Kirsten Han of the socio-political website The Online Citizen Asia, and Yahoo! Singapore published LFL’s statement on their social media accounts. Not long after, the POFMA office issued a correction order and the following had to be appended at the top of their posts: “This Facebook post contains false statements of fact made by Lawyers for Liberty. The Singapore Prison Service does not use any of the steps in the alleged procedure for judicial executions.” The group was also required to post a link to the government website which countered LFL’s allegations.

Commenting on the correction direction, Han noted that before it was issued, she had sent questions to the Singapore Prison Service following up on the allegations and seeking more information about executions and how they were carried out in Singapore. The Online Citizen had also sent similar queries to the prison service. But instead of replying to them, a POFMA order was issued.

“I am concerned about how this affects the ability of journalists, activists, and ordinary citizens to follow up on allegations,” Han says. “This is particularly relevant in daily journalism where things move quickly, deadlines are tight, and more information emerges as stories develop. These points were made in April last year, in an open letter to Minister for Communications and Information S. Iswaran from journalists.”

Earlier this year, the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) issued a correction order to the Singapore Democratic Party (SDP) over two Facebook posts and an article on its website which it claimed to be false statements of fact. The article and the posts asserted that the employment of Singaporean white-collar workers had decreased, and their unemployment had risen. According to the MOM, there has not been any rising trend of retrenchment among Singaporean white-collar workers. It then published data from its Labour Market Survey to show that the number of retrenched employees had fallen between 2015 and 2018, instead of rising.

The SDP countered by citing the same survey and asserted that it interpreted the statistics from 2010 onwards, whereas the Ministry’s interpretation was from the period between 2015 and 2018. Chee Soon Juan, the Party’s secretary general, said that the MOM’s use of the period 2015 to 2018 was “arbitrary” and that neither their interpretation nor MOM’s was false since different time frames were used. SDP decided to challenge the correction order before the High Court, saying the differences in interpretation of statistics should not be subject to a correction order by POFMA. Chee argued that the government’s reluctance to disclose comprehensive information and statistics was also why disparities in interpretation exist and insisted that their interpretation was accurate given the amount of data available.

Since POFMA went into force, all but one of the correction orders it has issued were targeted at politicians, activists, and journalists. This confirms widely held suspicions that the government’s reason for wanting to combat online falsehoods was in fact to quash dissenting voices.

After a two-day closed hearing at the High Court, the judge dismissed SDP’s appeal and agreed with the prosecution that the statements they put out were false, based on the statistical evidence provided by the government. But Justice Ang Cheng Hock also noted that, “Unlike the minister, who is able to rely on the machinery of state to procure the relevant evidence of falsity, the maker of a statement often has to contend with far more limited resources.” He added: “For a statement-maker, who may be an individual, to bear the burden of proof would put him in an invidious position.”

In response to the verdict, SDP issued a statement saying, “We reiterate our case which we argued in Court: POFMA must only be applied to clear-cut cases of falsehoods, not for interpretations of statistical data.”

Since POFMA went into force, all but one of the correction orders it has issued were targeted at politicians, activists, and journalists. This confirms the widely held suspicions that the government’s reason for wanting to combat online falsehoods was in fact to quash dissenting voices. When asked about this claim by the Nominated Members of Parliament, Anthea Ong and Walter Theseira, Iswaran said it was a mere “coincidence.”

Critics as unpatriotic Singaporeans

When Thum and two activists met Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammad in Kuala Lumpur in late August 2018, news of the event quickly spread in Singapore. During that meeting, a wide range of issues were discussed, including LGBT rights, women’s rights, and the challenges facing the Malay community in Singapore and Malaysia. After that meeting, Thum posted on his Facebook page that he had met the Prime Minister and urged him to play a leading role to promote democracy and freedom of expression in Southeast Asia.

In response, politicians within the ruling party, mainly Shanmugam and Member of Parliament Seah Kian Peng, started to question Thum’s motives and whether he was betraying Singapore by doing so.

Soon after, a social media campaign involving pro-ruling party social media accounts was waged against Thum. His credentials as a historian were questioned and he was branded a traitor to the country. Prominent figures in Singapore such as former diplomat Bilahari Kausikan also publicly questioned his loyalty. Kausikan called him a “slippery character.” This narrative about him being a traitor to his country was amplified by the State media, leading many Singaporean netizens to question whether Thum and the activists had indeed betrayed Singapore by trying to lobby the then Malaysian Prime Minister.

The spread of false narratives is a tried and tested tactic. It is not uncommon for members of Singapore’s ruling elite to cast aspersions on the loyalty of opposition politicians to paint them in an unfavorable light. When opposition politician Chee criticized the ruling PAP at events overseas, he was branded a traitor to the country by the late Lee Kuan Yew. In his book Democratically Speaking, Chee said Lee called him “a liar, a cheat, and altogether an unscrupulous man … a near psychopath.” He also quoted the elder Lee as saying, “I could also add that I’ve had several of my own doctors who are familiar with such conduct … tell me that he is near-psychopath.” Similarly, the current Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Hsien Loong, the eldest son of the elder Lee, described him thus: “a liar, he’s a cheat, he’s deceitful, he’s confrontational, it’s a destructive form of politics.”

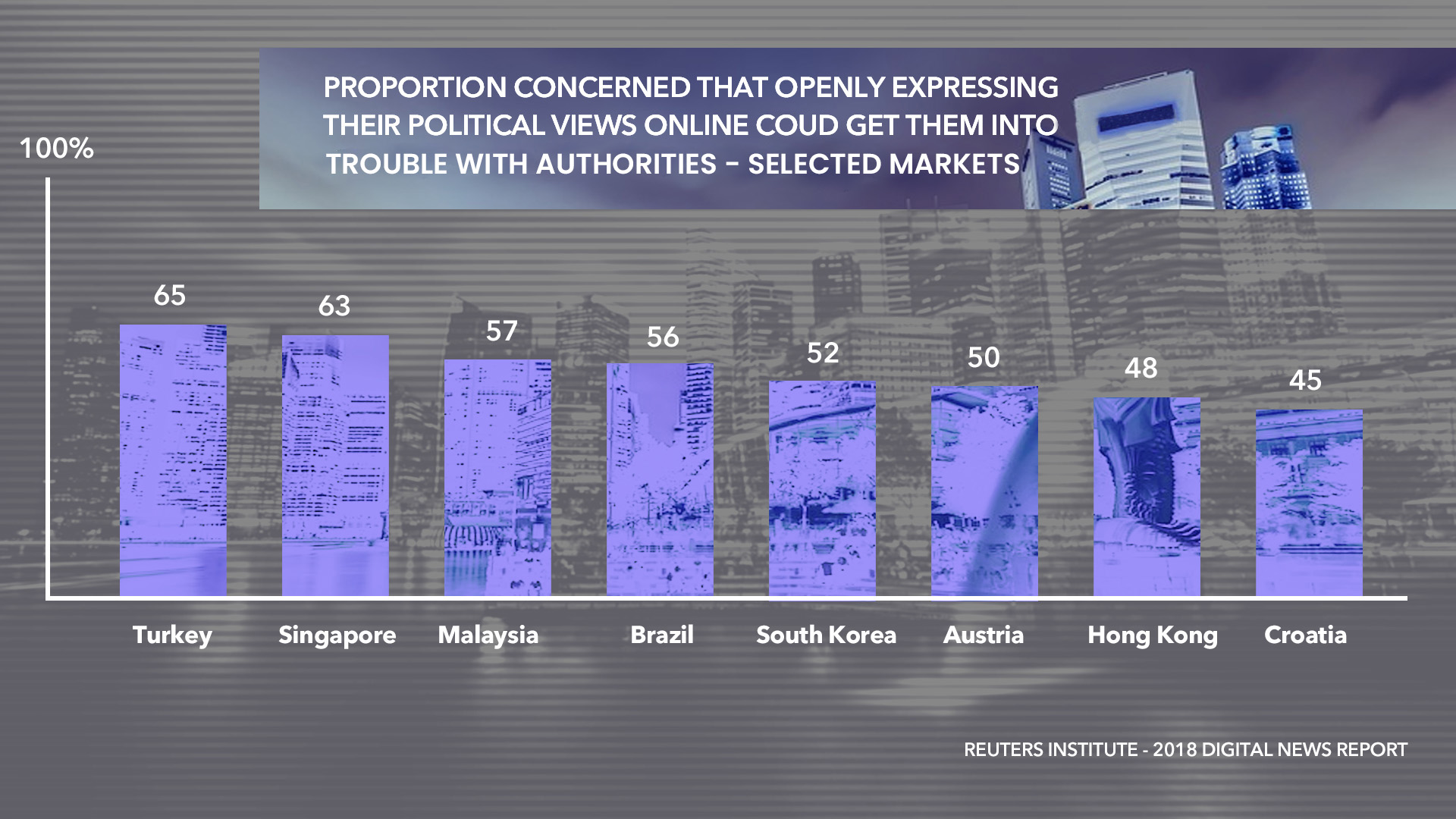

Findings shown by the graph above were based on an online survey commissioned by Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism “to understand how news is being consumed in a range of countries.” Please visit: https://agency.reuters.com/content/dam/openweb/documents/pdf/news-agency/report/dnr-18.pdf

Journalists interviewed for this article said they do not feel optimistic about the state of press freedom in Singapore. Even though social media has provided a platform for people to organize themselves and express their views, many are afraid of doing so. In a 2018 Reuters survey among approximately 2,000 Singaporeans, 63 percent revealed that they were afraid of expressing their political views openly for fear of running into trouble with public authorities.

“In the last few years, there’s definitely been a chilling effect on free speech,” said a journalist in one of Singapore’s major media publications, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “I think what many of my peers and colleagues see is that the government and the ruling party is not interested in the diversity of views [but is] intent on perpetuating a single narrative,” she says.

“In the newsroom, it is definitely difficult now to push the envelope on issues which I want to write on because of the insistence [of the State] on certain prescribed narratives. And the culture of fear is very strong.”

Thum and Han, she says, “are publicly shamed because they try to push a counter narrative in their work. We see this also with how they banned [Tan] Pin Pin’s film, so the signals are very strong.”

“All the various lawsuits and POFMA correction orders send a pretty clear signal to us journalists that we need to toe the line. I don’t think much has changed. In fact, things might even be worse. The PAP is still using defamation lawsuits and charging people who are a thorn in its flesh,” she says.

“This is classic PAP under Lee Kuan Yew, and I don’t see the situation changing much, given all that is happening,” she concludes. ●

Singapore has had a long history of trying to silence dissent. In recent years, the city-state has ridden the wave of growing international anxiety over disinformation and fake news and has passed a sweeping legislation to help combat it: The Protection Against Online Falsehoods and Manipulation (POFMA). It came into force in mid-2019 and half a year later was used by the Ministry of Manpower against the Singapore Domestic Party over posts on social media. The High Court has ruled in favor of the law early this year.

Jolovan Wham is a civil rights activist who has campaigned actively for freedom of speech and expression, migrant workers’ rights, and other human rights issues in Singapore.