Release rates in Southeast Asia are relatively higher, but political prisoners are largely excluded

By Verlie Q. Retulin

[dropcap font=”Georgia” size=”80px” background=”” color=”” circle=”0″ transparent=”0″]T[/dropcap]he first time I set foot here, I felt like I was being choked.”

This was how inmate Guillermo Busano described his first few moments inside the Philippines’ Manila City Jail, one of the world’s most congested prison facilities.

Clad in bright yellow shirts, his fellow inmates stood behind bars. Others sit naked, shoulder to shoulder, using an old, folded cardboard to cool themselves while being cramped in humid cells. The stench of their sweat filled the air.

“Where am I? Why am I here? What is this place?” Busano asked, weeping.

It was the first strike in his initiation to hell.

Amid the ongoing pandemic, governments around the world have implemented various interventions to facilitate the release of inmates and decongest jails. Yet, a regrettable flip side of this move is an intensified clampdown on lockdown protocol violators, many of whom are sent to already-crowded detention centers, thus increasing the risk of transmission of the deadly coronavirus.

‘Ticking time bombs’

Jail and prison congestion readily emerged as one of the human rights concerns confronting the COVID-19 pandemic, in the wake of reported intensified overcrowding of prison facilities that were already in decrepit conditions before today’s health crisis swept the world.

Asian prisons, in particular, have been described as “ticking time bombs,” with experts warning that “[they] will be near impossible to manage if COVID-19 takes a real hold.”

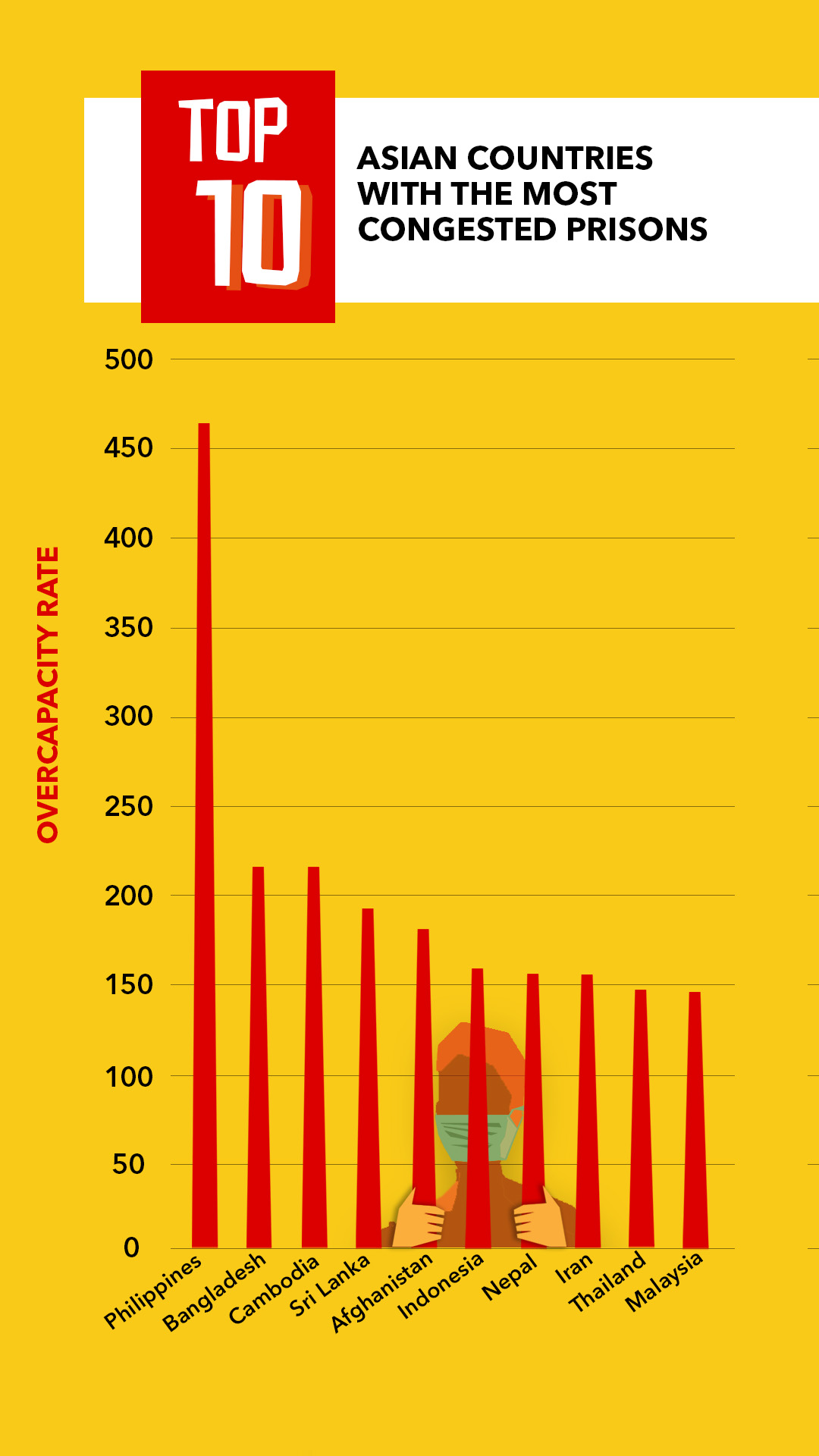

Source: World Prison Brief

In Asia, 18 out of 48 countries have prisons exceeding their regular capacity. The Philippines is at the top of the list, with prisons four times more overcrowded than South Korea. It also has the second highest congestion rate in the world next to the Republic of Congo.

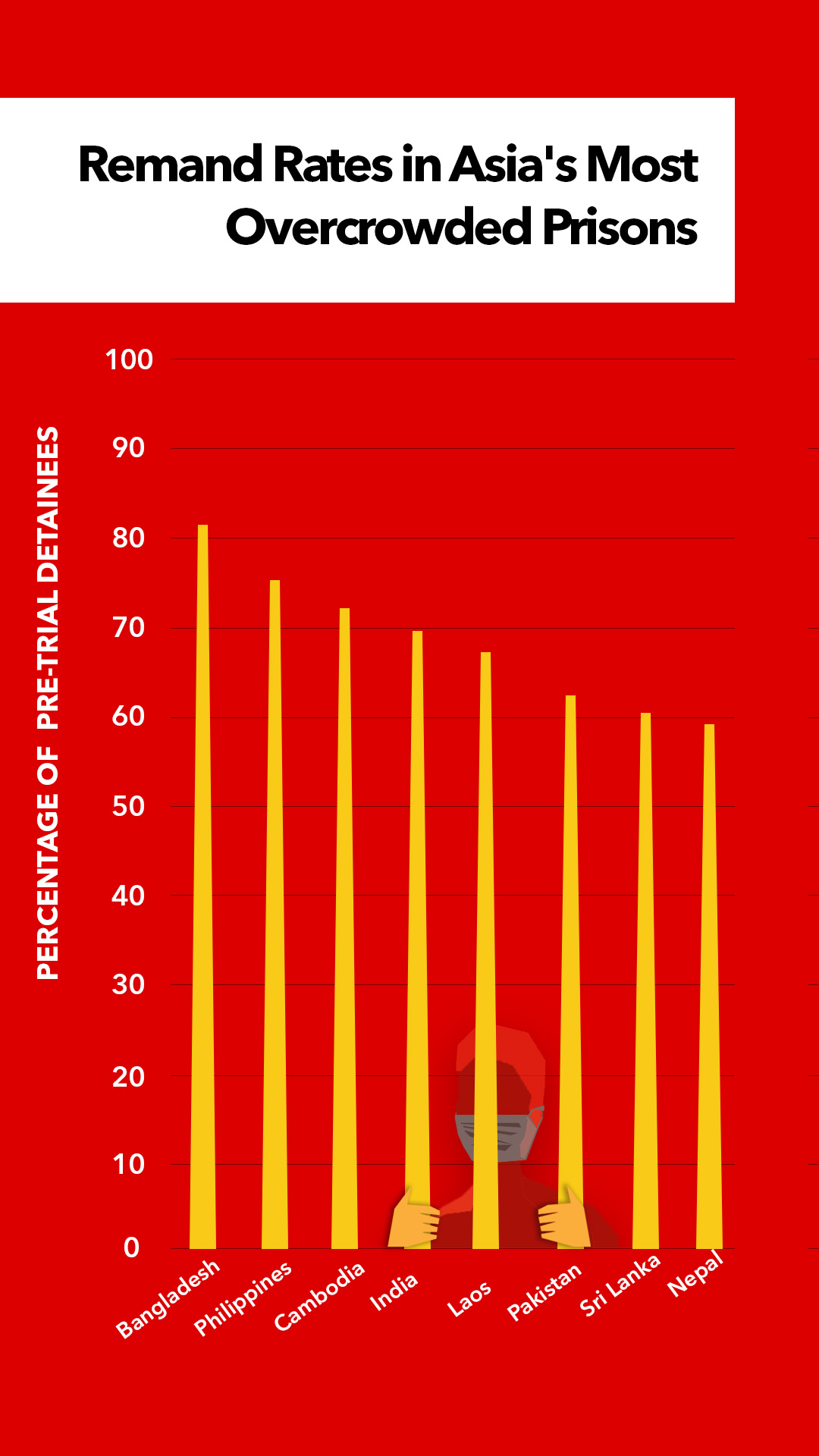

Source: World Prison Brief

In Asia, Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Cambodia are the top three countries with the most overcrowded prison facilities. They also have the highest rate of detainees remanded on bail or in custody.

Currently, prisons in the Philippines, Bangladesh, and Cambodia, for instance, are at over 200 percent capacity, according to World Prison Brief.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) has pointed out that the large percentage of pre-trial detainees in many Asian countries is a major factor in the overcrowding.

Overpopulation in detention centers makes physical distancing impossible; other factors, including the inmates’ inability to observe proper hygiene and the lack of adequate medical equipment to respond to an outbreak, compound the risks.

Lockdown violators arrested

Asian countries such as the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, and India have implemented lockdown procedures to restrict citizen movement and prevent the spread of the coronavirus. While some violators were reprimanded and fined, many others have been arrested and detained — a move that civil liberties advocates consider counterproductive. In the Philippines, state forces have arrested 177,540 people as of May 22 for allegedly defying quarantine protocols. Of this, 30 percent or 52,535 individuals have been detained, mostly in police detention centers.

“It’s counterproductive, it’s unnecessary,” says Raymund Narag, assistant professor at the Southern Illinois University’s Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice and a former inmate himself, noting that it is a “very criminal justice response to a public health problem.”

“It’s really difficult to follow quarantine rules, especially for those who live in depressed, informal-sector, communities. They have to work to be able to survive. Unfortunately, they are being seen by some as ‘hard-headed’. [And] if that’s [the case], then it’s so easy for … Filipinos to accept the narrative that the police should be high-handed,” he explains in a mix of English and Filipino.

“And, if you have leaders saying, ‘Arrest them and shoot them if they refuse to obey,’ then it will be very easy and justifiable for our police enforcers to do just that,” he adds. “That’s where human rights violations happen.”

He cites, for example, the severely humiliating punishment imposed on a group of violators who were thrust into a dog cage to deter repeat violations or other potential offenders while lockdown restrictions were in place. This sets off a cycle of situations where people are forced to resist aggressively or violently when confronted or apprehended by police for violating lockdown rules, he says, resulting in graver charges such as resisting arrest/assault of persons in authority.

In Malaysia and India, poor workers were also arrested, and in some cases beaten up, by the police when found to have breached stay-at-home orders while looking for sources of income to feed their starving families.

In Indonesia, the National Commission on Human Rights (Komnas HAM) has identified arbitrary detention and criminalization as among the potential human rights violations during the implementation of movement restrictions. This, while the country’s Justice and Human Rights Ministry announced in April that they would be releasing 50,000 prisoners to reduce prison overcrowding.

“Some people are being detained in the name of protecting the people from COVID-19,” says Fatia Maulidiyanti, head of the International Advocacy Division of The Commission for the Disappeared and Victims of Violence (KontraS). These include individuals who are found violating the government’s large-scale social restrictions.

“We know that overcapacity will happen in police detention. And there are no rapid tests or other health protocols that are being applied to those detained, especially in the rural areas or in other regions in Indonesia,” Maulidiyanti says.

In Malaysia, human rights concerns were raised during the first month of implementation of the Movement Control Order (MCO), a set of preventive measures issued on March 18 under the Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases Act of 1988 and the Police Act of 1967. By this time, Suara Rakyat Malaysia (SUARAM), a local human rights group, had noted that around 7,500 individuals had been arrested, more than a quarter of whom were charged in court. By April 26, the number had increased to 15,000.

Arrests were initially reduced after the police were given discretionary powers to impose a fine – RM1,000 ($234) – on MCO violators instead of bringing them to court. However, the respite was short-lived as prison sentencing for MCO violations was eventually reinstated. The Malaysian Prisons Department had earlier called on the court to stop sending violators to prison to prevent COVID-19 outbreaks. They should be ordered to perform compulsory community service instead, it said.

Malaysia’s prisons has an occupancy level of 142.3 percent as of December 2019. Like other Asian countries, its prisons are overcrowded and in poor conditions, resulting in the rapid spread of diseases.

Dobby Chew, SUARAM’s documentation and monitoring coordinator, says violations leading to the arrests were caused by public confusion about the MCO policies. “It could start in the morning saying you can do this. In the afternoon, you’ll receive another text message contradicting the earlier announcement. Then, towards the evening, they’ll allow it again but only under specific conditions; otherwise, you’ll get arrested.”

SUARAM also cited other abuses committed under the MCO, including preferential treatment of public figures, juvenile arrests, as well as extrajudicial and degrading treatment of violators.

In May, a series of raids conducted in designated COVID-19 “red zones” — districts with more than 41 cases of coronavirus within a two-week period — led to the apprehension of at least 2,000 undocumented migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, according to news reports.

“They’ll go in there, knock on every door and check the documents. If you’re an undocumented migrant worker, you’ll get arrested. You’ll then board a truck to the detention facility, with no masks, no protection, and no social distancing [observed],” Chew says. Photos have circulated online of migrant workers lined up in close quarters and wearing only masks.

On May 26, Malaysia reported its highest daily increase in new coronavirus cases since April 3. Most of these were traced back to the country’s detention centers, where detained migrants and staff workers alike were infected.

To make matters worse, the government has pursued “a very organized campaign … to push a narrative that illegal migrants and refugees are not welcome [in Malaysia]. They should get out of the country. They should just go to jail. They should all suffer and die, whatever [kind of] death they will have,” Chew says. “It’s pretty nasty in that sense.”

Half of an estimated 6 million migrant workers in Malaysia are deemed illegal.

Decongesting prisons

On March 25, United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (UN OHCHR) Michelle Bachelet urged governments to examine ways to release persons particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 including the elderly, those with underlying health conditions, and other low-risk offenders.

Several countries acted accordingly and hastened the release of some of their detainees. In India, prisoners who have been detained for minor offenses, are over the age of 60, sentenced to jail for 6 months or less, or with chronic illness, were allowed to be released. Thailand also freed prisoners facing minor offenses and/or are exhibiting good behavior.

Criteria for Prisoner Release in Southeast Asia

| Country | Minor Offense/Pre-Trial | Age Consideration | Political Pardon | Length of Time Served | Health Considerations |

| Cambodia |

X |

x | X |

X |

|

| Indonesia | X | X | |||

| Malaysia | |||||

| Myanmar | X | X | |||

| Philippines | X | X | X | X | |

| Thailand | X | X | X |

Source: Various news reports from March 1 to June 21, 2020

Various interventions have been implemented in several Asian countries to decongest jails. In many Southeast Asian countries where overcrowding has been noted, the criteria include age and health considerations, as well as length of sentence served.

In the Philippines, 22,522 persons deprived of liberty (PDLs) were released between March and May 2020, averaging 7,500 monthly. Narag points out, however, that this is also the same monthly average of inmates released in the country in normal times, or a total of 90,000 annual releases, citing data from the Bureau of Management and Penology. To make a dent in jail congestion, particularly in the wake of the pandemic, at least 60,000 inmates should be freed, Narag says. Yet, in doing so, there are other legal and social impediments to consider, such as poor inmates’ inability to post bail.

Two months after OHCHR issued its appeal, global prison releases have been “too few and too slow,” says HRW. Only 5 percent of the global prison population has been authorized for release, with many of the orders to this effect still awaiting implementation, says the international rights watchdog.

Prisoner Release Rates in Southeast Asia

*Release rate refers to planned release over total prison population. Data as of June 21, 2020./ Source: Various news reports from March 1 to June 21, 2020, World Prison Brief

Release rates in Southeast Asia are relatively higher compared to the 5 percent global average noted by Human Rights Watch. The releases, however, exclude political prisoners.

Political prisoners not counted

PDLs released to date as an anti-pandemic measure hardly include political prisoners. As the HRW has noted, “releases in some countries specifically exclude human rights defenders and others wrongfully imprisoned for peacefully exercising their rights to freedom of expression, assembly and association.”

Agnes Callamard, UN’s special rapporteur for extrajudicial summary or arbitrary executions, has appealed for the release of political prisoners, human rights defenders, and those facing “ridiculous charges.”

In Indonesia, Maulidiyanti of KontraS says political prisoners charged with treason and prisoners on death row cannot be released. In the Philippines, a petition was filed in April with the Supreme Court for the release of 22 political prisoners on humanitarian grounds, since they are either “elderly, sickly, or with medical conditions that require continuous monitoring and treatment.”

Two months on, and amid reports that the country has registered its largest single-day rise in confirmed coronavirus cases, their petition is still pending before the court. One of them already gave birth in prison while waiting for the court’s response to their petition. ●